Wöbbelin - The Liberation

In May of 1945, WWII was in its final phase and there was no longer any organized German resistance to the allied occupation. A and B Batteries, 319th Glider Field Artillery of the 82nd Airborne, led by Major Fred Silvey, were focused on vetting German civilians to determine who were Nazi officials, who were members of the SS, and who were soldiers dressed in mufti (civilian clothes) in order to avoid detection.

Major Silvey’s men searched for hidden stores of arms and ammunition, as there was still an enormous amount of abandoned military material to be collected.

The discovery of Wobbelin

Word came at this time that a concentration camp, named Wöbbelin, had been discovered a few miles north of the town of Ludwigslust. On May 2 the camp was discovered by Allied scouts and on May 3, the gates to the camp were opened. The scene inside was out of a nightmare. Hundreds lay dead in open burial pits.

Among them were French, Dutch, Polish, and Belgians who ran afoul of their Nazi occupiers. Others were members of trade unions or communist-inspired organizations. Some were suspected of resistance activities against the Nazis. (see photos below)

Prisoner barracks

Hundreds more desiccated human bodies were stacked in heaps or scattered haphazardly around the compound, some still lying in their crude—and cruel—barbed-wire bunks.

Wöbbelin was part of the large Neuengammen concentration camp complex in Hamburg. It was built hurriedly over the previous winter. Its purpose was to accommodate prisoners who were being evacuated from larger concentration camps in Poland, to the east of Wöbbelin, that were steadily being overrun by advancing Soviet Forces.

Conditions inside the women’s camp

The Wöbbelin Concentration Camp was actually comprised of two separate camps. The smaller, original camp was begun in September of 1944. Known as Reiherhorst, this facility was of decent construction quality with electricity and basements in some of the buildings. Once Reiherhorst was completed, it became the barracks for the slave-labor work crew that then began building the rest of the Wöbbelin complex.

Ultimately, Reiherhorst became a labor camp for female prisoners. Women held there were kept busy sewing Nazi flags, banners, and other propaganda in an on-premises factory. Living conditions at Reiherhorst were marginally better than at Wöbbelin itself...at least the sleeping bunks were known to have been made of wooden boards and not raw barbed wire.

Male prisoners’ barracks

The male prisoners’ barracks, known collectively as Wöbbelin, were another matter entirely. Although made of bricks, they were poorly and hastily constructed and left unfinished. The floors were bare earth, and the doorways and windows were open to the weather. Inside was a scaffold of barely milled green lumber. Two tiers of bunk beds (see photo below) were then fashioned using only barbed wire stretched across the framework. This is what the male prisoners slept on. Raw, uncovered barbed-wire. The Nazis didn’t seem the least concerned about the comfort of their captives.

The entirety of Wöbbelin included a half dozen barracks, a kitchen, and a lazarette (a type of crude hospital/quarantine station). And all of it set within a stark, treeless parade ground surrounded by a double barbed-wire enclosure with a watchtower at each corner. The barracks were arranged in a herringbone pattern to allow the greatest field of fire between the buildings from the two towers. Easier to shoot prisoners. The Nazis thought of everything.

On the outside of the barbed wire were barracks for the SS guards, as well as, storehouses and utility buildings.

In mid-February of 1945, with the end of WWII only a few months away other, more easterly concentration camps, were being evacuated and overrun. 700 political prisoners were hastily moved into Wöbbelin.

Arrested by the Nazis

Only a minority of Wöbbelin’s prisoners were Jews. And at least one was a Catholic priest. Most were Poles, French, Dutch and Russians who were either prisoners of war or slave laborers. Arrested by the Germans in 1943 for editing a political publication with the Paris Underground, David Rousset, a philosopher, and journalist had recently been transferred to Wobbelin. He survived captivity and dedicated his life to exposing Nazi concentration camps. Since Wöbbelin was a labor and detention camp, and not an extermination camp, it did not have any gas chambers or crematoria. Prisoners were viewed as a free labor source and were put to work in nearby Ludwigslust and surrounding areas.

Over the next ten weeks German occupied areas in the east began shrinking and shrinking. As they did, Wöbbelin grew from 700 to over 4,000 prisoners. Deaths rose from about 100 per week to a multiple of that number as the camps’ infrastructure began to collapse.

Jews from Budapest as young as 13 years old

When the American 8th Infantry and 82nd Airborne Divisions finally liberated Wöbbelin on May 3, 1945, there were roughly 3,500 living prisoners still confined behind the barbed wire. While at the same time hundreds of dead bodies were strewn throughout the camp - the victims of starvation, disease, unimaginable abuse, and monstrous human disregard.

Most of the Wöbbelin prisoners walked or were escorted away from the camp on that very day - May 3. But a substantial number remained in order to receive critical medical attention.

The dead were left just as they’d been found

Throughout the day on May 3, more and more living prisoners were moved to army hospitals as their conditions stabilized.

The dead were left just as they’d been found. A stark reminder to confront the townspeople of Ludwigslust, who had so greedily taken advantage of the forced labor.

At this same time, May 3, 1945, Captain Charles Sartain, the 319th’s CO for A-Battery, paid an impromptu visit to Wöbbelin. Whether he and his driver, Louis Sosa, were motivated by the rumors or the horrid stench in the air, Sartain was determined to investigate the concentration camp.

When he arrived at Wöbbelin, Sartain found the former concentration camp locked up tight and guarded by MPs of the 82 Airborne Division. All the while medical personnel were tending to the survivors. “The medics wouldn’t let the average GI go in,” Captain Sartain later explained, “wouldn’t let us give them anything. They needed immediate medical attention before anything else, even food. The former prisoners were hollering, pleading, and begging us to let them out. But we could not.” (see photos below)

Starving men fight for food while others too weak to move

Sgt. Henry Broski HQ-Battery (above left) 319th Glider Field Artillery oversees C-Rations for starving prisoners

U.S soldiers stand guard as prisoners carry another who had fallen from weakness and starvation

The living were moved to US Army hospitals

319th ordered to inspect the camp

The very next day, May 4, a directive came from HQ that as many of our men as possible should see Wöbbelin with their own eyes. “I was in favor of it,” said Sartain, “I wanted them all to see the horror like I did.” So beginning on May 5, each battery took its turn visiting the former Wöbbelin camp.

PFC Carl Salminen’s memory was that every man in A-Battery “had to go, no ifs, ands, or buts about it. We had to go see it. It was an order. So that we’d always remember what the Nazis did here.”

The 82nd Airborne inspect male prisoner camp

The men of A-Battery piled into weapons carriers and made the trip to Wöbbelin. Not all eventually went. Not all really wanted to see the horror. But most did go, if only out of curiosity, to see the worst crimes of our Nazi enemies. And what they saw was worse than any of them could imagine.

Led by Lieutenant Marvin Ragland, men of the 82nd Airborne Division including Kenneth Smith, Ted Simpson, Carl Salminen, Joe D’Appolonio, Mahlon Sebring, Bob Storms, Ted Covais, William Bonnamy and several dozen others piled into trucks to personally witness the gruesomeness they had been ordered to see. On the way to Wöbbelin they passed through the town of Ludwigslust, an attractive little burg of about 5,000 citizens. Interestingly, the town was intact. The U.S. Army had made a strategic decision not to destroy it.

Although they were on their way to an atrocity site, the men’s spirits were good. After all, the war was almost over, the weather was beautiful, and they were still alive. All that remained was the formal surrender of the German Army. That upbeat mood changed suddenly. First, a foul odor filled the air. Then, they saw the outermost perimeter of barbed wire fencing. It looked like there were scraps of discarded clothing along the fence line.

On closer inspection, the men of the 82nd saw that the rags contained human bodies. Astonishingly thin, emaciated bodies. Inside the rags! They looked like frail marionettes whose strings had been cut.

Before wandering off, the men of A-Battery stood there in eerie silence and tried to make sense of the scene around them. The seven or eight stark buildings, the empty parade ground, the deserted watchtowers - were like one monumental crime scene. Lieutenant Ragland remembered that of the final hundred or so survivors who remained at Wöbbelin, “About all they could do was move their eyes.”

“They were all dressed in black and white vertical stripes,” SGT Ted Covais recalled. “Most had dysentery or typhus. They were emaciated, bony. (see inset photo) Their cheeks were sunken in. Their arms were like sticks. There was hardly any flesh on their arms and legs. Half dead. Starved.”

The sadness the medical crew saw that day was overbearing. No one was rejoicing. No one was smiling. The prisoners had been through so much and now it was over. But you couldn’t call them happy. These people were profoundly sad.

American soldiers guard one of the enclosures - May 4, 1945

Tec 5 Lee Patterson of the 307th Airborne Medical Detachment recalled, “ The camp is about four or five miles outside of the town that we are in now; it’s on the main highway and in full view of anyone who passes, places without knowing some of the horrors that went on inside of the double barbed wire enclosure. Of course, you have to go inside the camp itself to see the real filth and desolation that is there, but the groans of the dying and the stench of the dead are evident even from the highway. As we drove up to the gate, a small boy stood there just outside the camp. He was thin and emaciated and his ragged clothes barely covered his filthy body. We smiled at him and received only a vacant stare from his completely lackluster eyes. We drove inside and stopped the ambulance and got out. An old man trudged up to us and began speaking in English. ‘Will it be possible for us to leave here tonight,’ he asked us? We didn’t know, but we told him we thought he would leave that night or the next day. I wished to high heaven that he could have gone from that place that very minute, but there was no telling what awful disease he carried and it would have been very dangerous to have taken any of them away until a suitable place was prepared for them all. He asked us to come with him to see where he and some of his friends lived. Again, he asked if it wasn’t possible for him and the others of his group to leave with us and big tears streamed down his cheeks. I’m not sure just why he cried; it was probably a combination of joy at being liberated and fear of having to spend another night in hell. As we were walking with him to the building he lived in, another prisoner came and beckoned for us to follow him. We told the old man, he was a Dutch political prisoner, that we would be with him in a few minutes and followed the British guard and the other prisoner.”

Tec 5 Lee Patterson

“There we saw the sight that I’d heard and read about so many times. There was the sight that had been photographed and printed before. There was the sight that until now, even with all of the articles I had read and the pictures I had seen, I had passed off as so much propaganda. In a little alcove at the end of the long barracks was piled about 20 or 30 dead bodies. There was no way to be sure of the number, because they were stacked one on top of the other as shovelfuls of manure might be piled.”

Patterson continued, “There was absolutely no attempt made to preserve any of the dignity that surely belongs to the dead. There was no cover over them and there was no attempt made to lay them in an orderly fashion. They were just thrown in and left to lay where they might drop. Each body there, I’m sure, died of starvation and malnutrition. I looked at one body lying there on the ground. The impression of the backbone was plainly visible from the front. There seemed to be no abdomen or stomach – only the skin of the front of the body covering the backbone. The eyes were open and staring, and as I looked at them, I felt mighty guilty for not having hated the Germans enough before. Well, there they were – all of those dead humans. There was nothing any of us could do about it. Hating the Germans or the people directly responsible for such an atrocity isn’t going to help them. There’s no punishment to fit the crime in this case. Only the wrath of God, himself, can ever do justice to the criminals who were responsible for such a crime. And the criminals are not only the people who had a hand in the crime itself, but it includes the others who stood by and let such a thing happen…and that probably includes just about all of the Germans in Germany. There was still a worse sight to come. I started over towards the old Dutchman we had first met (I call him an old Dutchman—he may have been quite a young man for all I know) and they called us over into a long barracks. There, lying on the ground just where they had passed away, I think, were about 40 or 50 more of the dead. They were just the same as all of the others. They probably hadn’t been dead as long…”

Strewn with corpses and the stench of death

SGT Covais led a “tour” of the barracks

“We didn’t dare give them any food”

The tour of the Wöbbelin barracks buildings was short and very unpleasant. The stench of disease and death kept all but the most inquisitive from looking any further. The compound was strewn with corpses, puddles of excrement, and blood. One of the worst parts of this experience for the soldiers of the 82nd was turning a deaf ear to the entreaties of the survivors begging for something to eat. “We didn’t dare give them any food. The medical team forbade it.”

Ted Covais led a tour of the barracks. When he passed the corner of one building he found himself staring at the most horrible sight he’d ever seen in his life. “There was a pile of naked bodies on the ground, about four or five feet high, stacked like cordwood outside the building. It was as if the Nazis wanted to stack as many bodies as possible in this ungodly mound. They were efficient if nothing else.”

“How could any human being treat another like this, as if they were just garbage?” Covais asked no one in particular. “The injustice and the inhumanity towards these people was unimaginable,” he went on to say.

The lazarette building, which was a crude field hospital, wasn’t anything like a real hospital at all. It was more like a house of death. The tour of the lazarette was particularly gruesome for the men of the 82nd Airborne Division. The place was literally so filled with corpses that the American liberators were unable to push the front door completely open.

Cremation pits:

In a far corner of the compound, where a quarry had once been, were mass graves and a cremation pit. The half consumed bodies that lay in the ashes were a hideous, nightmarish reminder of a horror that would stay in the liberators’ memories for the rest of their lives. No way to ever erase, or un-see, what these men saw. Although many members of the 82nd Airborne Division had seen photos of prisoners in other concentration camps, the horror of seeing Wöbbelin in person was much worse, almost indescribable.

Lieutenant Ragland, Ted Covais and Carl Salminen crossed the railroad tracks that ran between the men’s and women’s camps to inspect Reiherhorst. The SS, the elite guard of the Nazi Reich, was transferring new female prisoners ( see photos below) to Reiherhorst as late as the morning of May 2, immediately before the guards disappeared. We assumed the guards got word that Germany surrendered and decided to slip away into the night before the allies arrived.

Women prisoners driven to near insanity

Ted Covais remarked that some women prisoners had been driven to near insanity. They were screaming and pleading with the American soldiers to help them. But there was nothing we could do until the medical team had done their job.

Female prisoners liberated from the labor camp.

The soldiers of the 82nd then proceeded to the textile factory. It was a large room with three or four dozen Singer Sewing Machines. Bolts of cloth and rolls of machine embroidered insignias were strewn about the place. Black, white, and red were the only colors the Nazis used.

Shock had already turned to disgust and anger by the time all the American soldiers returned to their trucks. Some of the men cursed the Germans, while others sat quietly, still trying to make sense of what they’d just seen. For the first time anyone could remember, the loquacious CPL Bob Storms had nothing to say. He sat alone, like he’d been weeping.

More than anything, every man now knew what he’d been fighting for. They were fighting for humanity, against inhumanity.

Suddenly, there was a fury amongst the GI’s to confront the German people who had perpetrated these appalling atrocities. Or turn a blind eye.

How could they not know about Wöbbelin

The very next day the citizens of the nearby village of Ludwigslust were trucked out to Wöbbelin and forced to confront the reality of what lay just outside their town limits. American MPs funneled the Germans through the camp, maneuvering them so they were forced to step among and over dead bodies. We wanted the citizens to see up close what their countrymen had done. CPL Ted Simpson later wrote about that day. “The German women were respectfully dressed. Some were weeping at what they saw. The men, hats in hands, were properly solemn. (see photo inset below) But the whole thing was strange, as though the existence of Wöbbelin Camp was a complete surprise to the citizens of Ludwigslust. And yet, the stench of death had permeated the area for miles around. PFC Bonnamy scoffed at the idea, “How could they not know about Wöbbelin, we could smell it from miles away?”

Most of the American soldiers who visited the former concentration camp believed that the local Germans were fully aware of what had been going on at Wöbbelin. It was right there in their “backyard.” And yet they quietly stood by and tacitly sanctioned this horrible place, pretending not to notice the bodies or the smell.

Wöbbelin had only been in existence for several months. And in practical terms, there was little the local citizenry could have done about it. They weren’t prepared to stand up to the Nazi SS. To complicate matters for the German civilians, their government was losing the war and its entire governmental infrastructure was crumbling.

So during the short time that the concentration camp was operating the local population, in and around Ludwigslust, lived in fear of their lives. They were being bombarded by the allies on the west, while the approaching Russian army moved closer and closer to the town’s eastern flank. In the final analysis, there was no legitimate excuse for the culpability of the German civilians. Wöbbelin was in plain view. It wasn’t hidden. It was located just a few yards off the main road between Ludwigslust and the village of Schwerin.

So the locals had to know about it. Prisoners were working in the local villages. And the SS was even screening motion pictures for the German townspeople in one of the buildings at Reiherhorst. While an unpardonable violation of humanity was taking place under their noses, the good citizens of Ludwigslust simply pretended not to notice.

Human beings were treated like garbage

Reflecting back on the whole question of German complacency, Ted Covais later said, “When we went into Italy, nobody was a Fascist. When we went into Germany, nobody was a Nazi. The locals denied knowing anything about the concentration camp. They denied its very existence. They were adamant about it. They said it’s all propaganda. We would never do anything like that. But they did. They did.”

General Dwight D. Eisenhower orders all victims buried in a public place

Then, following a mandate from General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, the U.S. Army ordered “...all atrocity victims are to be buried in a public place, with crosses placed at the graves of Christians and Stars of David on the Jewish graves, along with a stone monument to commemorate the dead.”

Townspeople bury the dead in the Ludwigslust Palace Plaza

All day long on May 6 the citizens of Ludwigslust were forced to handle the corpses of over 200 victims. No gloves. No tools. Bare hands. The human remains were carried out to trucks and then brought to the town square for burial. “Our revenge was making them dig the graves,” Ted Covais noted. We wanted to shame the Germans, publicly. This is how we did it. Another eight hundred dead were buried in a woods, in common graves.

Funeral service and eulogy - May 7, 1945

On May 7, the 82nd Airborne Division conducted a mass funeral service for the deceased prisoners. Those in attendance included the citizens of Ludwigslust, captured German officers, five Wehrmacht Generals and several hundred members of the 82nd Airborne.

(see photo gallery below)

Mass funeral service for the deceased prisoners - in attendance 10,000 Germans filed by the funeral services. This included many captured German officers and five Wehrmacht Generals, as the 82nd Airborne stands guard - Service performed by Chaplain Wood - May 7,1945

The U.S. Army Chaplain George Wood who performed the service delivered a stinging eulogy to his audience:

“The crimes here committed in the name of the German people and by their acquiescence were minor compared to those found in other German concentration camps. Here there are no gas chambers, no crematoria. These men of Holland, Russia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and France were simply allowed to starve to death. Within four miles of your comfortable homes, 4,000 human beings were forced to live like animals, deprived even of the food you would give your dogs.

In three weeks 1,000 of these men were starved to death; 800 of them were buried in pits in the nearby woods. These 200 who lie before us in these graves were found piled 4 & 5 feet high in one building and lying with the sick and dying in other buildings.

The world has long been horrified at the crimes of the German nation; these crimes were never clearly brought to light until the armies of the United Nations overran Germany. This is not war as conducted by the international rules of warfare. This is murder such as is not even known among savages.

Though you claim no knowledge of these acts you are still individually and collectively responsible for these atrocities, for they were committed by a government elected to office by yourselves in 1933 and continued in office by your indifference to organized brutality. It should be the firm resolve of the German people that never again should any leader or party bring them to such moral degradation as is exhibited here.”

General James Gavin and his staff attend the funeral service - May 7, 1945

During interviews for this story most of the veterans were overcome with emotion as they relived their experiences of May 1945. Wöbbelin was the most common denominator in their stories. The focus of their worst memories.

When CPL Bob Storms was asked about Wöbbelin camp, he choked up. Through tears he explained, “I couldn’t go through it. I tried. I’d walk a little ways, and then I’d stop. I just couldn’t take it. I still get shook up. Even now. I guess I’ll never get over the memory of what I saw.

Photos courtesy of Joseph Covais, author of BATTERY, Carl Kienle, the family of George Cole and the 82nd Airborne Division War Memorial Museum

Wobbelin today

A modern, permanent exhibition on the history of the Wobbelin camp is located just outside Ludwigslust, Germany. There you will find a visitors center and library displaying various books, articles, and informational displays. Some literature has been donated by US Army soldiers who were present at the camp in May, 1945.

Visitor Center

Library display of Nazi shapes and colors used to identify victims - The 1945 camp register by name, date, serial number, and other identifiers.

A proper memorial site is located at the original spot of the campgrounds and barracks. Guided tours of the permanent exhibition and memorial site, organized talks with contemporary witnesses, as well as film screenings, lectures, readings, seminars, and workshops for visitors are available.

Wobbelin Camp Memorial Site

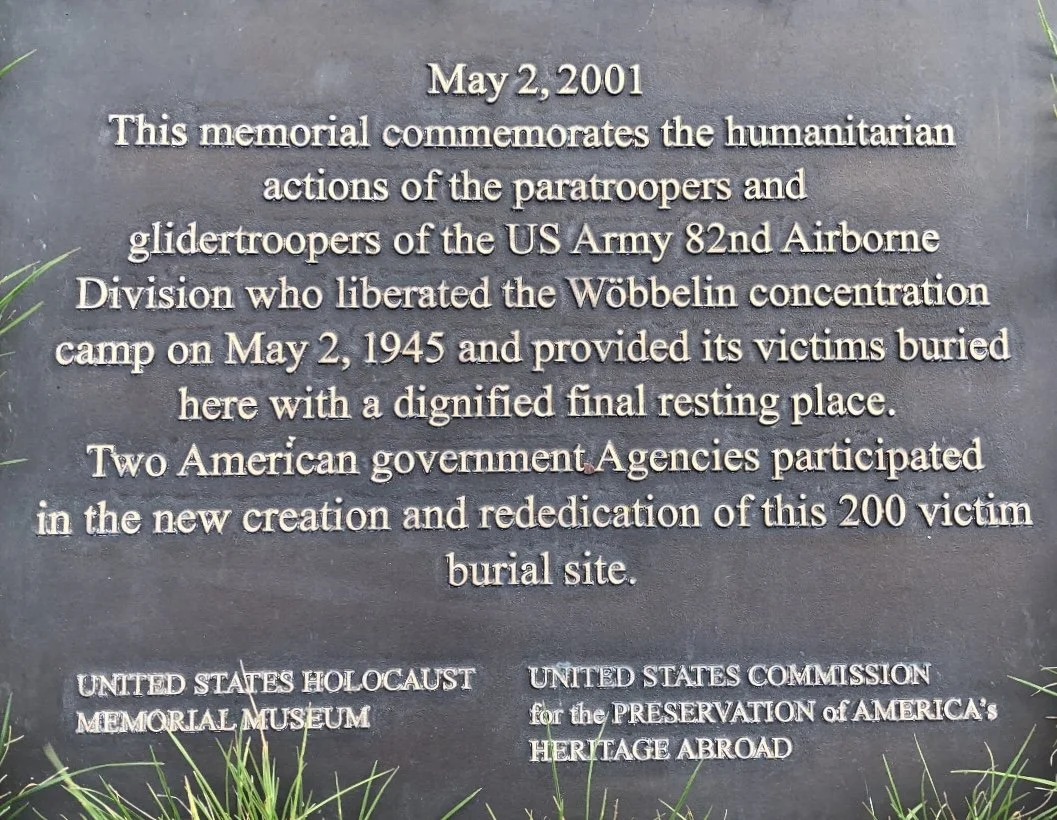

Photos below of the modern-day Palace Plaza and the 200 Wobbelin victims buried there. Two government agencies rededicated this site to preserve it as a dignified final resting place. The grounds are open to the public and the palace is now a tourist attraction.

An annual gathering of remembrance at the memorial site is conducted during the first week of May.