Growing up "Airborne"

William M. Bonnamy, Sr.

ASN:36382255

William M. Bonnamy, Sr. in Class A uniform with European-African-Middle Eastern Theater Ribbon with 1 Silver, 1 Bronze Battle Star

My dad, William M. Bonnamy, Sr., was a World War II veteran and I was a 10 year old kid who liked to explore. We had a crawlspace in the laundry room of our house and it was there I found a Nazi flag, a German bayonet and a Nazi belt buckle. Dad also had a trophy gun, stored on the top shelf of his closet where I couldn’t get to it (although years later I would). It was a semi-automatic blue-steel Walther kept in a worn, black leather holster. Occasionally, I would play with the flag or bayonet and try to imagine the stories behind these objects. At some point the flag disappeared, mom probably threw it out. I never asked. Eventually, I found dad’s war medals and a few photos. When I reached my 20’s, mom shared more photos and his discharge papers as well as a few other items that had been put away.

The footlocker in our crawlspace

I discovered a footlocker in the crawlspace above our garage in Chicago and the only way to get up there was on a ladder. In the ceiling I had to lift this square piece of wood that covered the hole and push it to the side to gain access. The process was slow and tedious because I wasn’t tall enough to see inside the opening. Unsteady on a ladder in the middle of the garage, I was scared to death my parents would come home and catch me. Eventually, I used a stick to lift open the top of the locker and got it to fall back into the open position. Reaching inside as far as possible I found an old pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes, of all things. The cigarette pack was black, the center red and Lucky Strike was in white. Why dad kept this pack of cigarettes, who knows. I was hoping to find his uniform but no luck. I did find his overseas cap, (see photo) written inside “Wm Bonnamy, D-G-2 and Army serial number 36382255.”

Wm Bonnamy, D-G-2 ASN: 36382255

Dad was an Airborne Paratrooper and Glider man with A-Battery of the 319th Field Artillery Group, 82nd Airborne. Occasionally, he would share a tidbit or reflection. You couldn’t needle or prod him for information but when he spoke you listened.

Dad’s Honorable discharge

German Paratroopers

A favorite subject I laughed about had to do with enemy soldiers, particularly German Paratroopers. Dad spoke as if he had some strange regard for them. A more formidable opponent than the average German soldier, he respected their ability. He said the 82nd found themselves fighting the same German Paratrooper units several times. Dad would joke that they were familiar enough with each other to yell from their foxholes, “Hey, Joe! How ya doing’?” and dad replied, “Hey Franz! I am doing’ pretty good, how are you doing?” As a kid that seemed strange, but the truth is he always added some humor to the story and a little sarcasm. Maybe that’s how he learned to live with some painful memories. He joked about it.

Our conversations were never long and always ended abruptly. I learned about the war and dad’s experiences one drip at a time. His honorable discharge record spoke for itself; 6 battle campaigns, 3 invasions including Italy, Normandy and Holland, 2 years, 4 months and 16 days over there.

At times dad could be pretty detached. I suppose two years of combat, numerous concussions, several glider crashes and more near death experiences than one could count eventually took its toll. I remember dad saying he thought of himself as a loner. He remarked, “You know I’m a loner, and you’re just like me, you’re a loner, too.” In some way, he was trying to tell me something I was too young to understand.

The All American book

Occasionally, he would mention something funny that happened, but if you pressed him for details, he would clam up. As a boy you want to know all about the shooting and the battles, the comic book version of the war. But he kept to himself about the more serious matters and I waited for the next opportunity to find out more.

Then, I discovered a maroon-colored, leather-bound book (see below) entitled Airborne and AA for All American. The book was published in late 1946 and contained the history of the 82nd Airborne but mostly focused on World War II. There were photos of paratroopers getting into airplanes, sitting in gliders, as well as strange caricatures and cartoons. The caricatures depicted soldiers, airplanes, cities like Paris, Nijmegen, and Oujda. Held together with black electrical tape, the book was free to members of the 82nd Airborne. The price tag for an extra copy was $5.00. In addition to soldier writers, artists and photographers, many well known people contributed items for the book. Norman Rockwell, Martha Gellhorn, Bill Mauldin, and virtually all the well known British and American generals.

The first page was a photo of the 82nd Airborne parading in victory through New York City on January 12, 1946; dedicated “To the valiant men of the Eighty-Second Airborne Division whose destiny laid them to rest in the fields of Sicily, Italy, France, Holland, Belgium and Germany.”

Next were pictures of unit arm patches and caricatures of soldiers. Images of paratroopers “earthward bound” and a Waco glider loaded with “glider men for the combat ahead.” A glider destroyed on landing, burning planes and tanks.

I’ll never forget the image of a paratrooper running with a Thompson M1A1 submachine gun and the caption “Attacking Under Fire an 82nd trooper.”

Shit on a shingle

The section on North Africa, a “prologue to combat” and Casablanca really got my attention. Dad’s unit sailed there in May 1943. I asked him about North Africa, but all he would say was “It was pretty hot, and we didn’t eat very well.” Seems there was a shortage of anything fresh to eat and dad developed blister-like sores on his arms that wouldn’t heal. “I had blisters that wouldn’t heal, we never got any fruit or decent food to eat, and it was always very hot.”

This was the first time I heard about spam. Dad hated spam, said that’s all the army fed him at Ft. Bragg. They served it every day, mostly on toast. He called it “shit on a shingle,” and would never eat spam again.

Dad swore the Army served goat meat at Fort Bragg, said it was terrible. Maybe even worse than spam. Jokingly, he would pronounce Fort Bragg in a goat’s voice like “Braaaaag.”

The more I read, I just couldn’t get enough of the 319th’s exploits in North Africa. But I could also sense something was on dad’s mind that he wasn’t ready to talk about. The photos and descriptions were fascinating. As a kid, It seemed so distant from any place I’d ever known.

Pages taken from the book “Airborne”

North Africa

Dad’s journey to Casablanca in North Africa began on the SS Santa Rosa, which left port in Staten Island, New York on April 29, 1943, carrying 2,500 servicemen of the 82nd Airborne. At one point during the trip, their ship split up from its convoy and the largest part proceeded toward Gibraltar, while the vessels carrying the 82nd continued to the Moroccan coast. Arriving in Casablanca on May 10, 1943, no one could leave the ship until General Ridgeway’s vessel had docked.

Sleeping Accommodations on the SS Santa Rosa

Canvas hammocks, stacked at least 4 tiers tall and as many rows as the location would allow. You would stay three days down in the hole and then 3 days on the deck.

The men spent several days in Casablanca and eventually proceeded by train northward along the African coast. The trip took approximately 8 days and made numerous stops along the way. The train was a specially furnished series of well-ventilated boxes stuck on wheels and fastened together with everything from dog chains to hairpins. They were built for transporting war material and had been labeled "40 men or 8 horses.” The trip included some sightseeing and occasional poker game.

“Forty and eight” train cars - Circa WW1 vintage held forty men or eight horses

The City of Oujda, Morocco was known for its good-looking women and downtown recreational center. There were a few bars and a thriving business in gasoline and shaving lotion. Many felt it was worth seeing.

“Knocked me out cold”

One day I commented on a cartoon like photo and suddenly, dad began telling a new story. Oddly, it started on a serious note, something happened in Oujda and I wasn’t going to miss a word. He looked away and said “you know one night I went to this bar alone, on the way out I got jumped – they robbed me, hit me over the head and knocked me out cold. When I woke up my money was gone…..I got back to camp and told the guys what happened.”

He then laughed, “Boy, did we clean that place out pretty good! We took care of those guys, they weren’t going to mess with the Airborne again – they weren’t going to mess with the 82nd!”

I pressed for more details but that’s all I got, never again was this incident discussed. In hindsight, perhaps this was a reflection of the many concussions he suffered throughout his service.

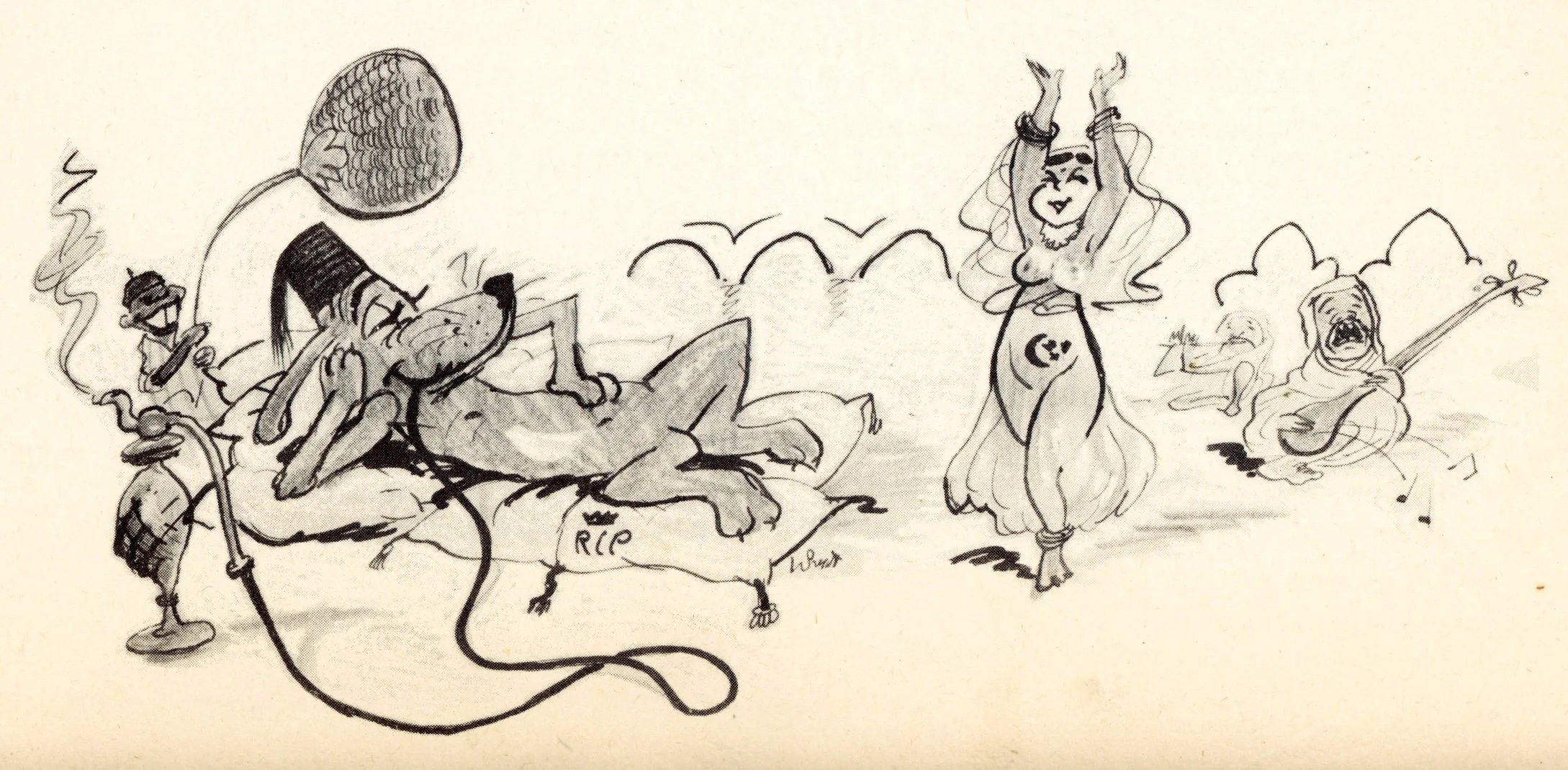

“One Night In Oujda” cartoon from the AA book

On May 18, 1943, the train arrived in Marnia, Algeria. The men bivouacked near an olive grove. Camp Marnia, as it came to be known, was for all the glider troops of the division as well as some British troops. The 319th spent the next few months training and moving from Marnia to Oujda and later, to Kairouan, Tunisia.

The troops found the daytime hours too hot to sleep. But since training was essential, it was mostly conducted at night. However, nighttime travel was perilous because civilians slept on the warm “army” wire mesh roads to avoid the cold desert night.

Poor rations and dysentery complicated matters. The men trained on the ground and in the air on gliders while bivouacked in the vicinity of Kairouan, Tunisia.

Too hot to sleep during the day, rocky, dusty, heat-seared and sick with dysentery.

Accidents happen

Conflict with civilians was unavoidable and complicated by the language barrier - not being able to communicate. Some locals couldn’t comprehend the importance of not trespassing in the training areas. They would wander around in the middle of the night. And, inevitably, accidents occurred. On June 18th, two civilians were unfortunately shot by members of the 325th Glider Field Infantry Unit at the rifle range.

As Generals Eisenhower, Gavin and Clark reviewed the troops, the men suspected their mission was southern Italy, but that wouldn’t occur until mid-September.

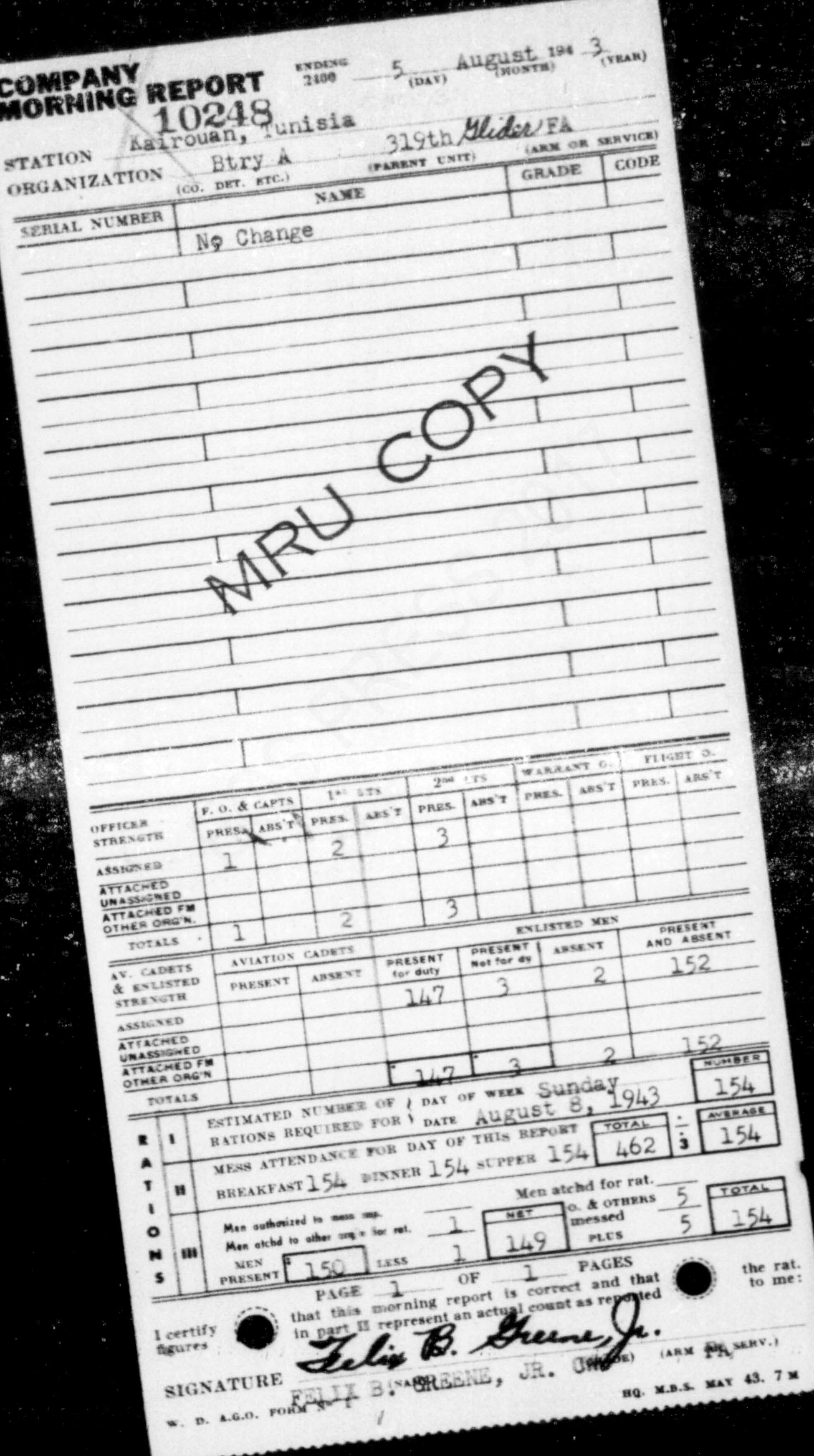

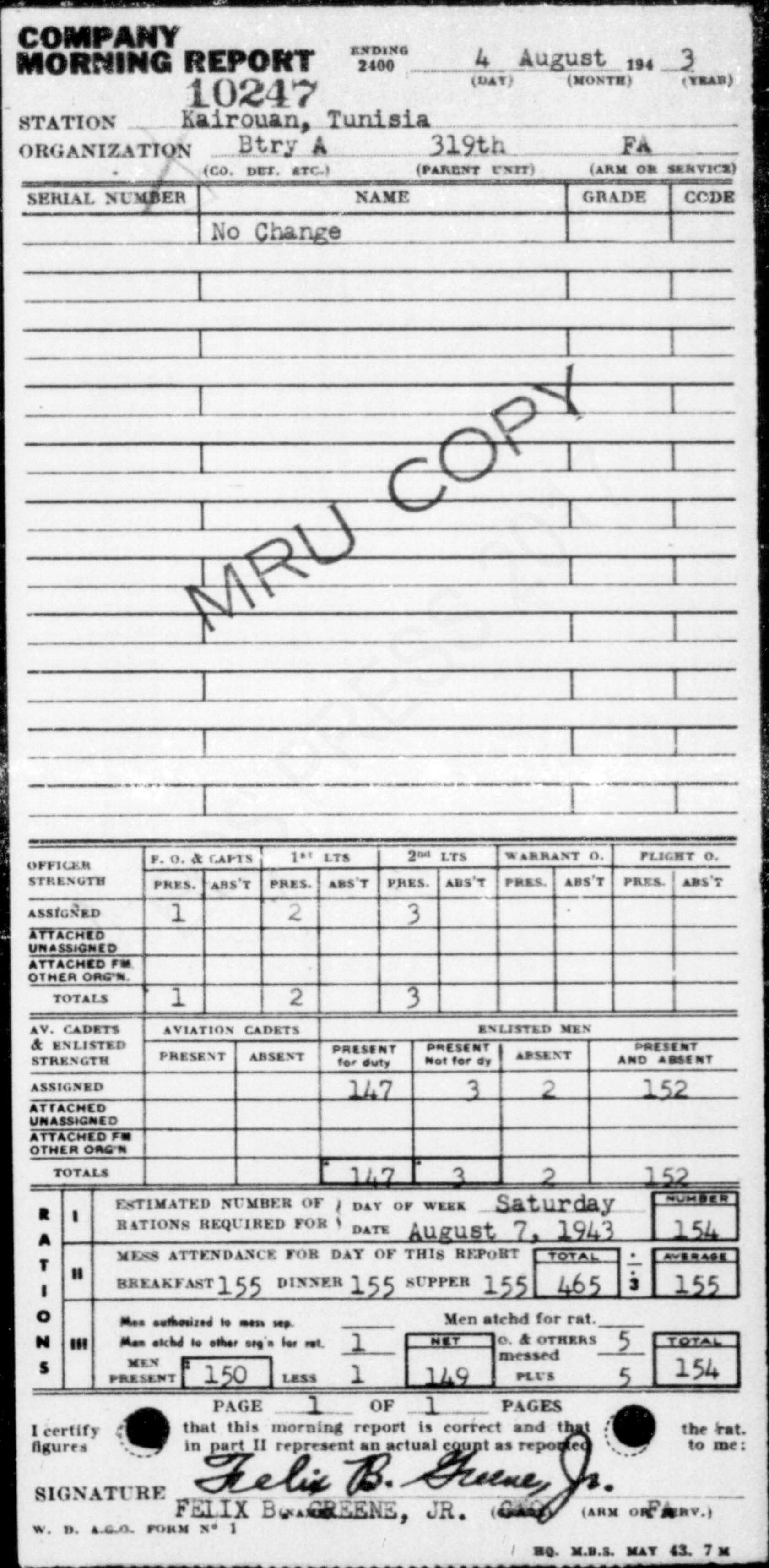

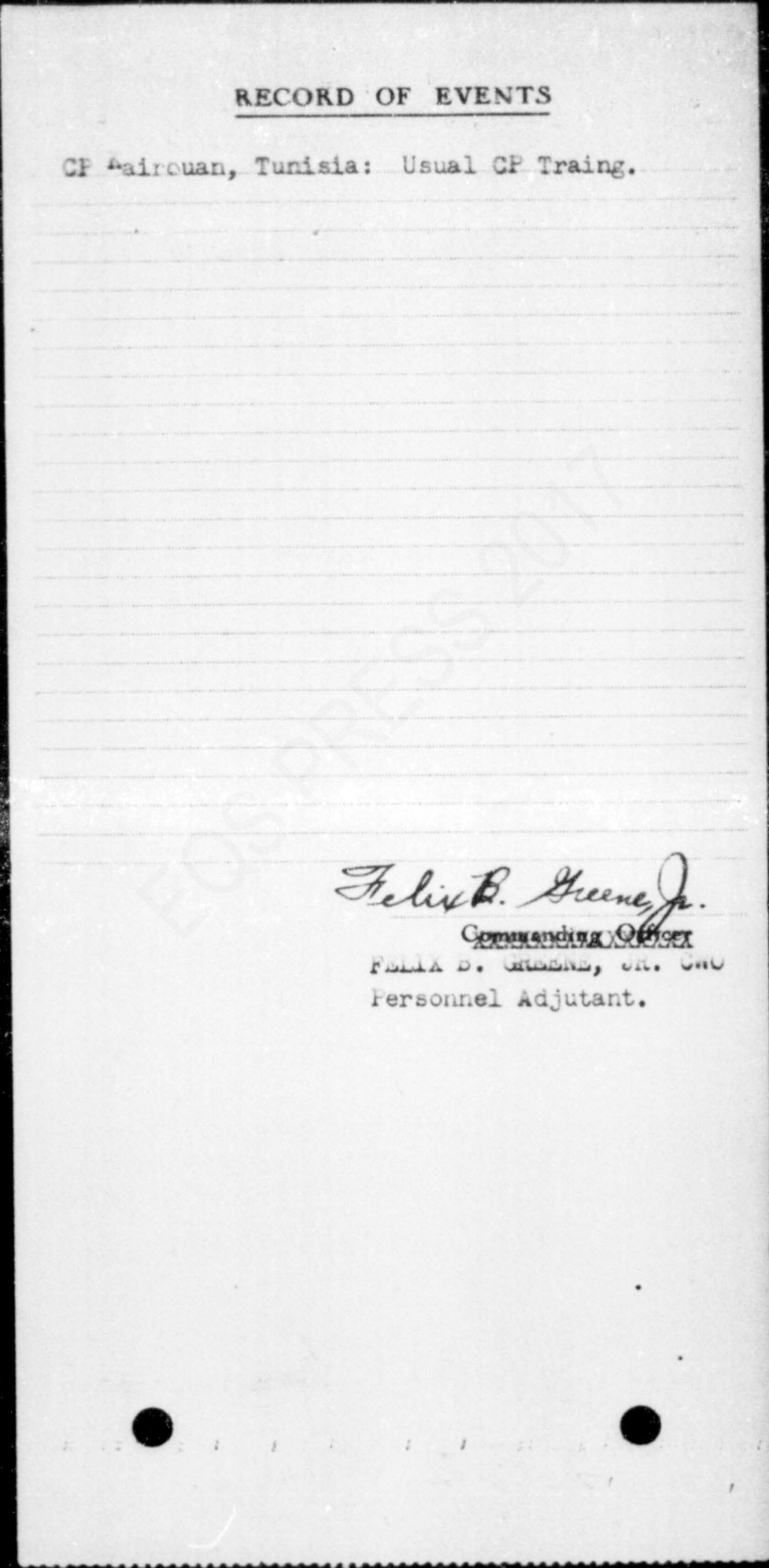

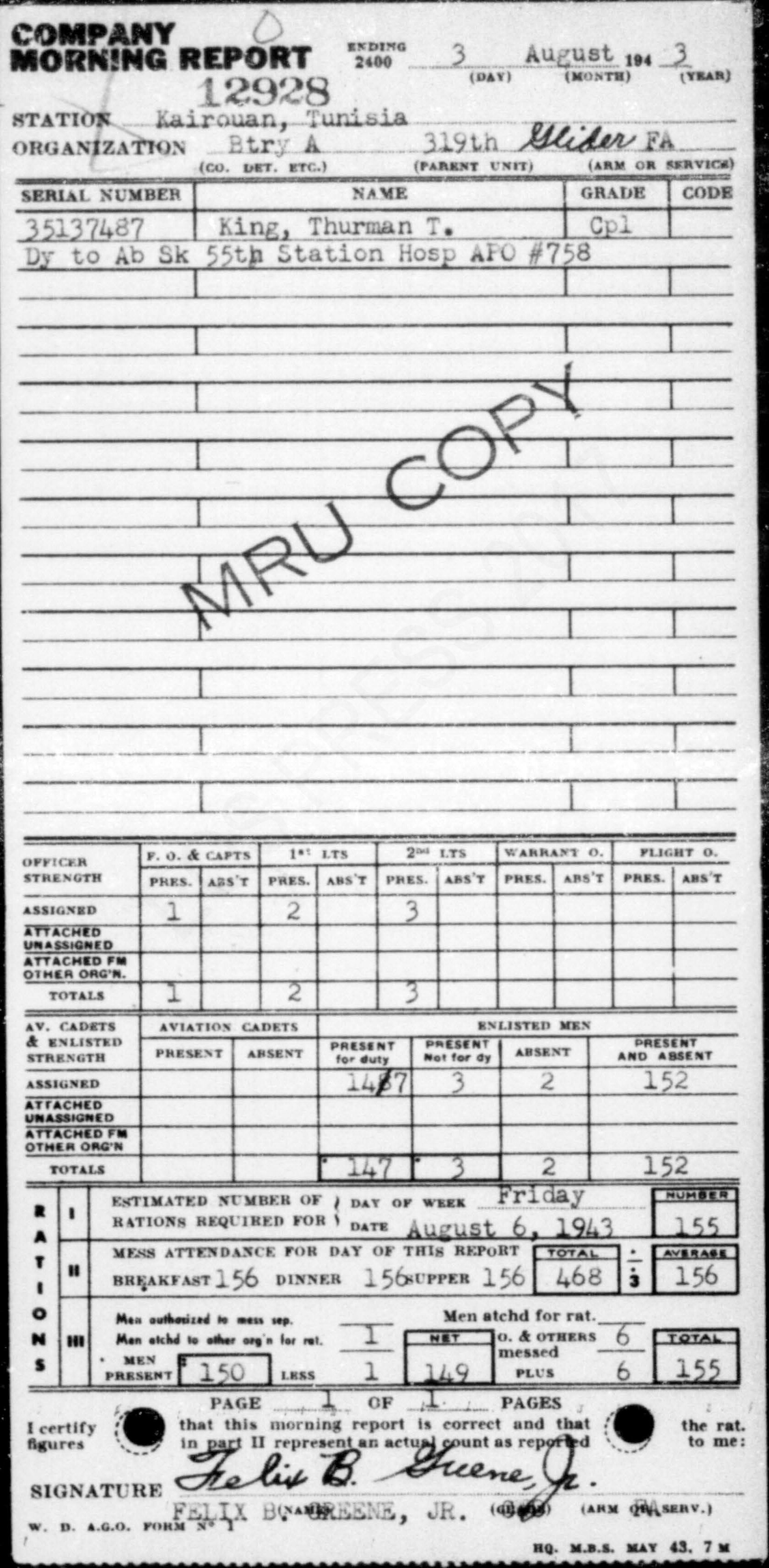

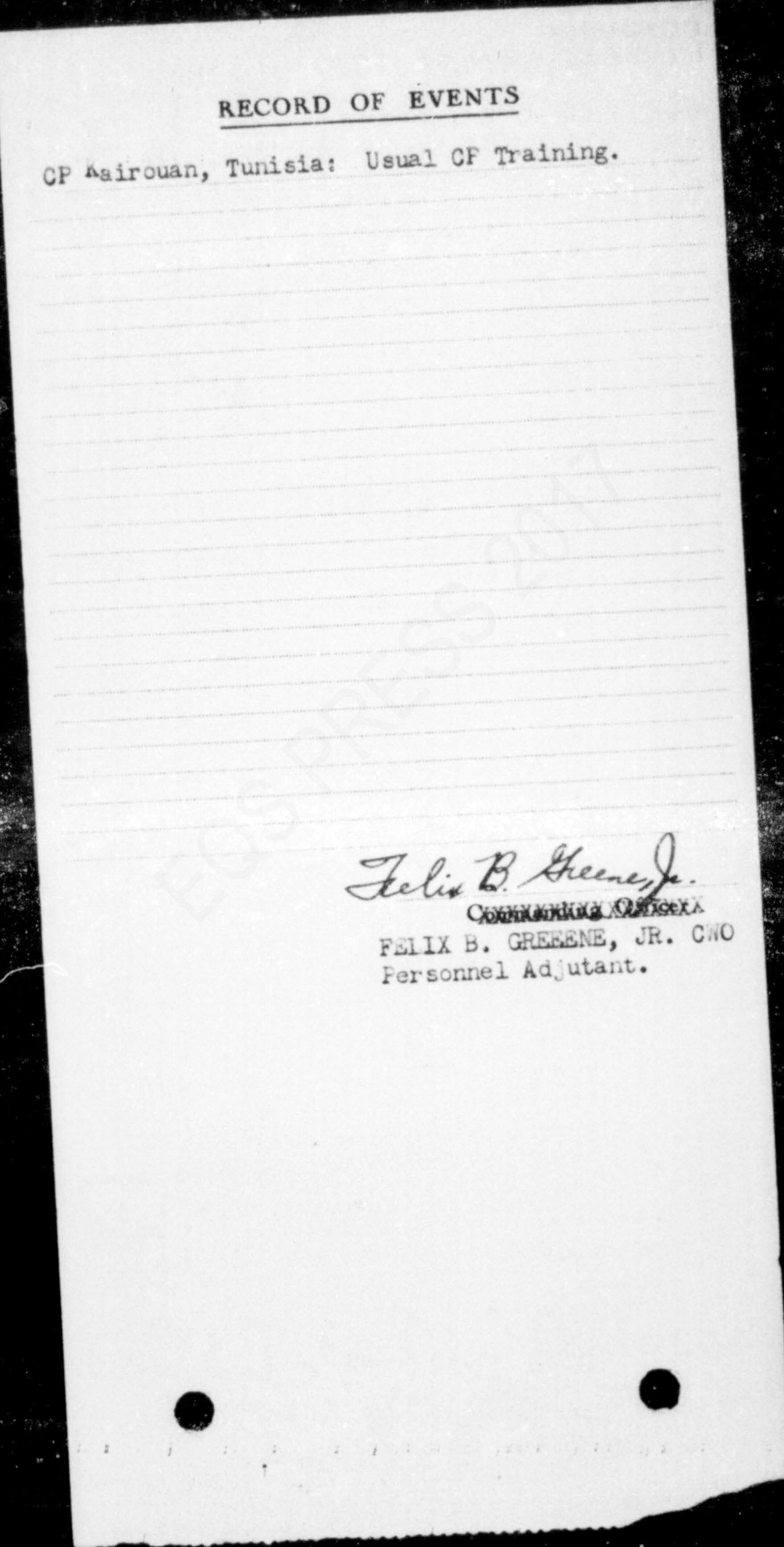

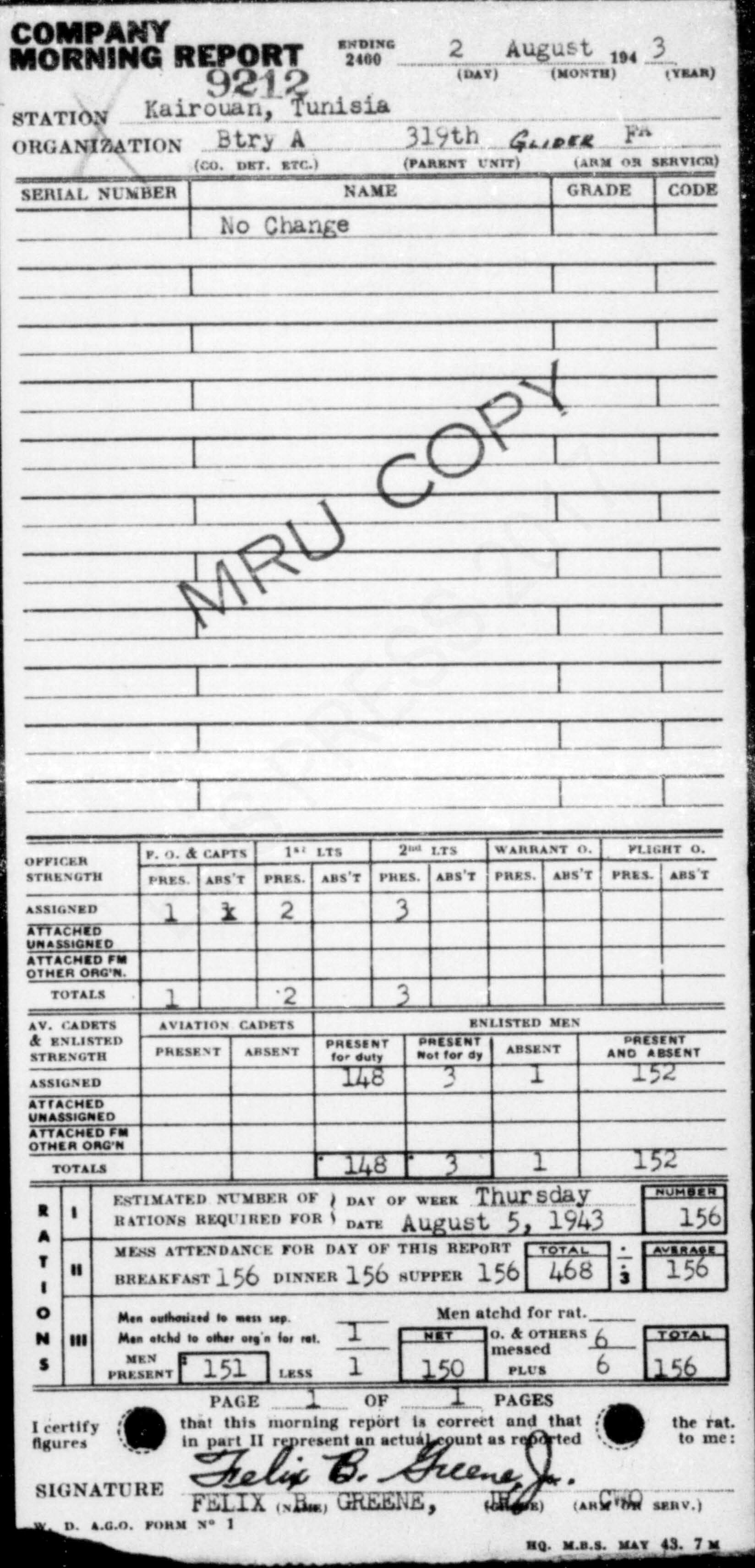

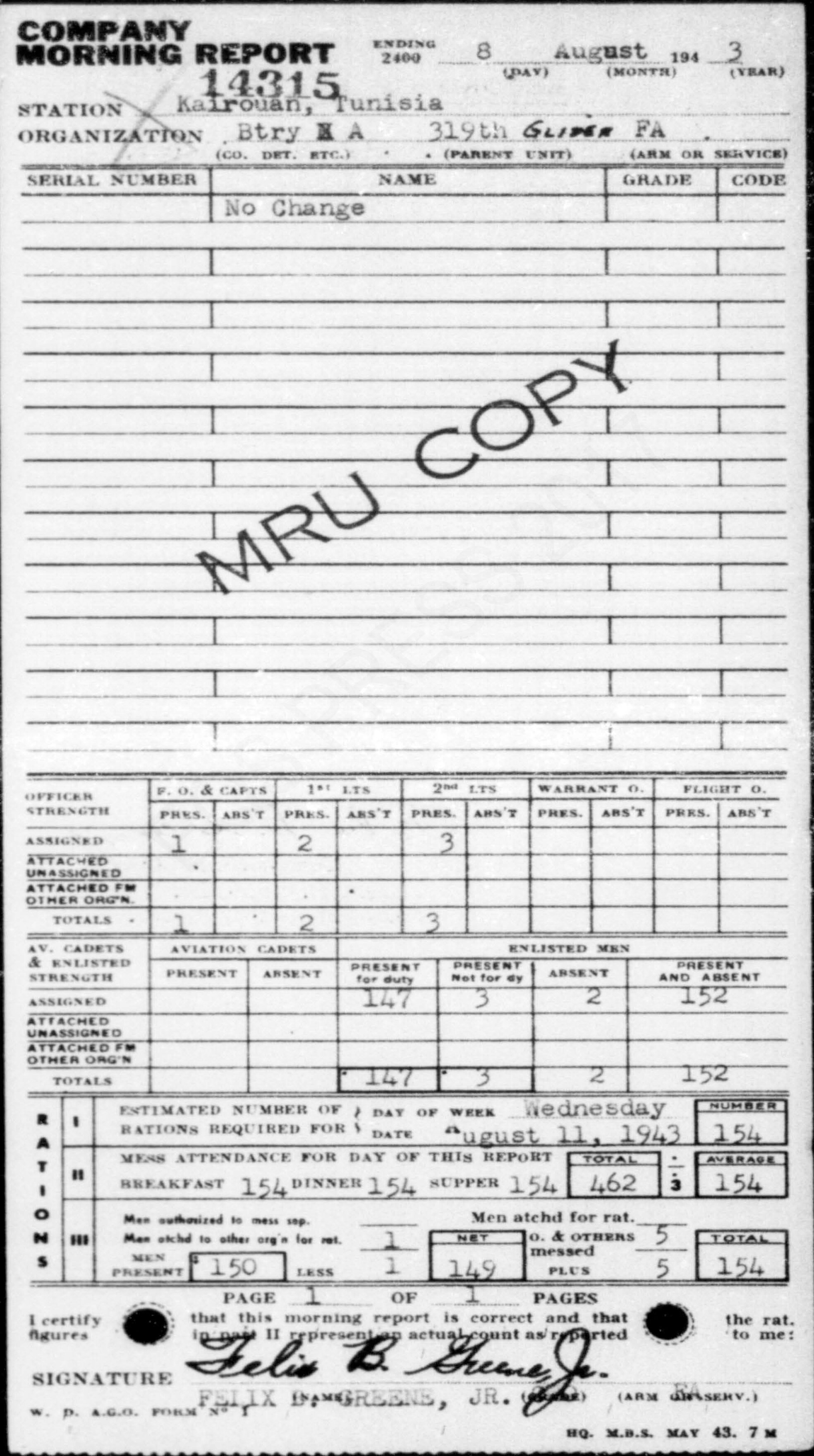

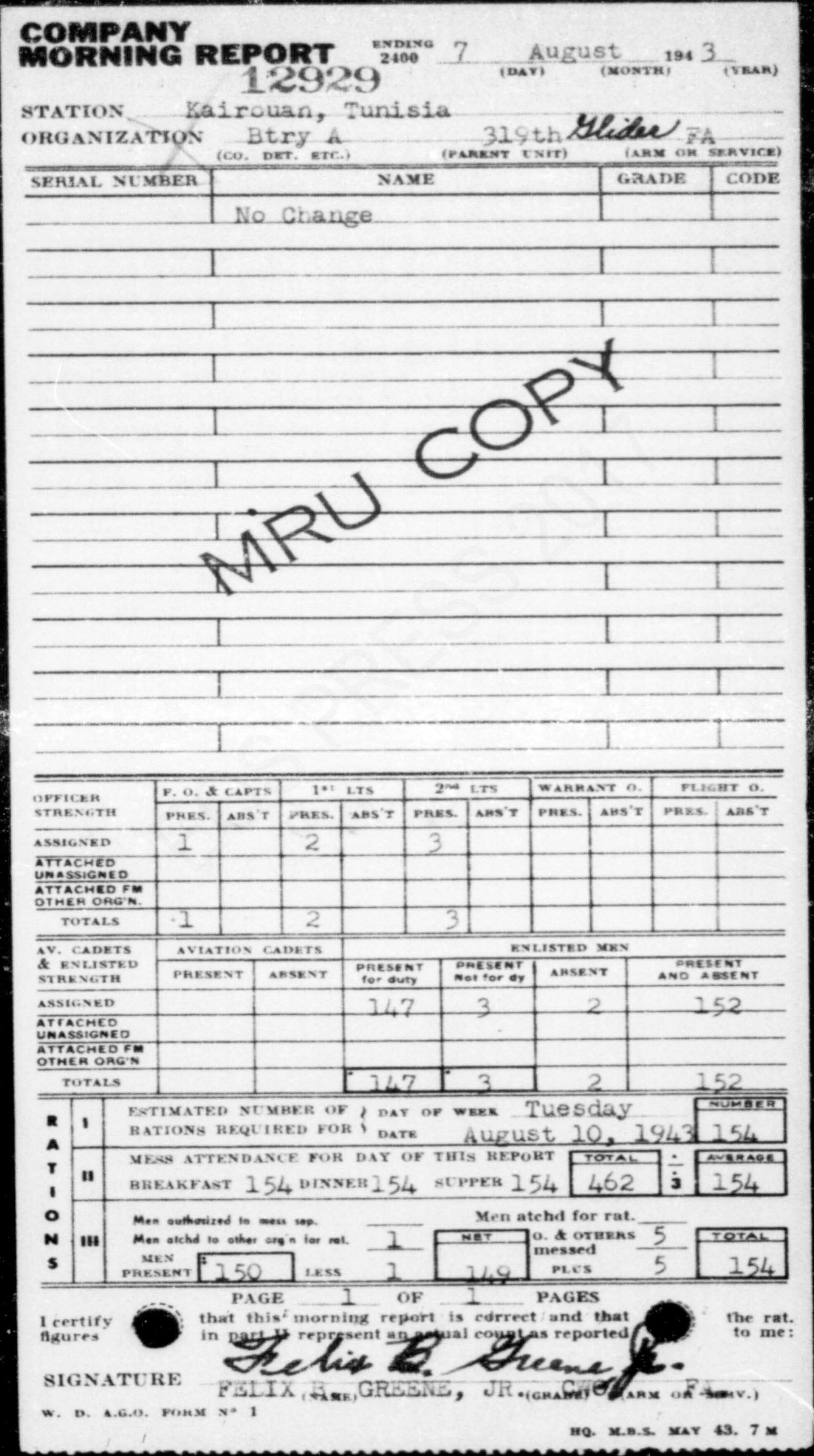

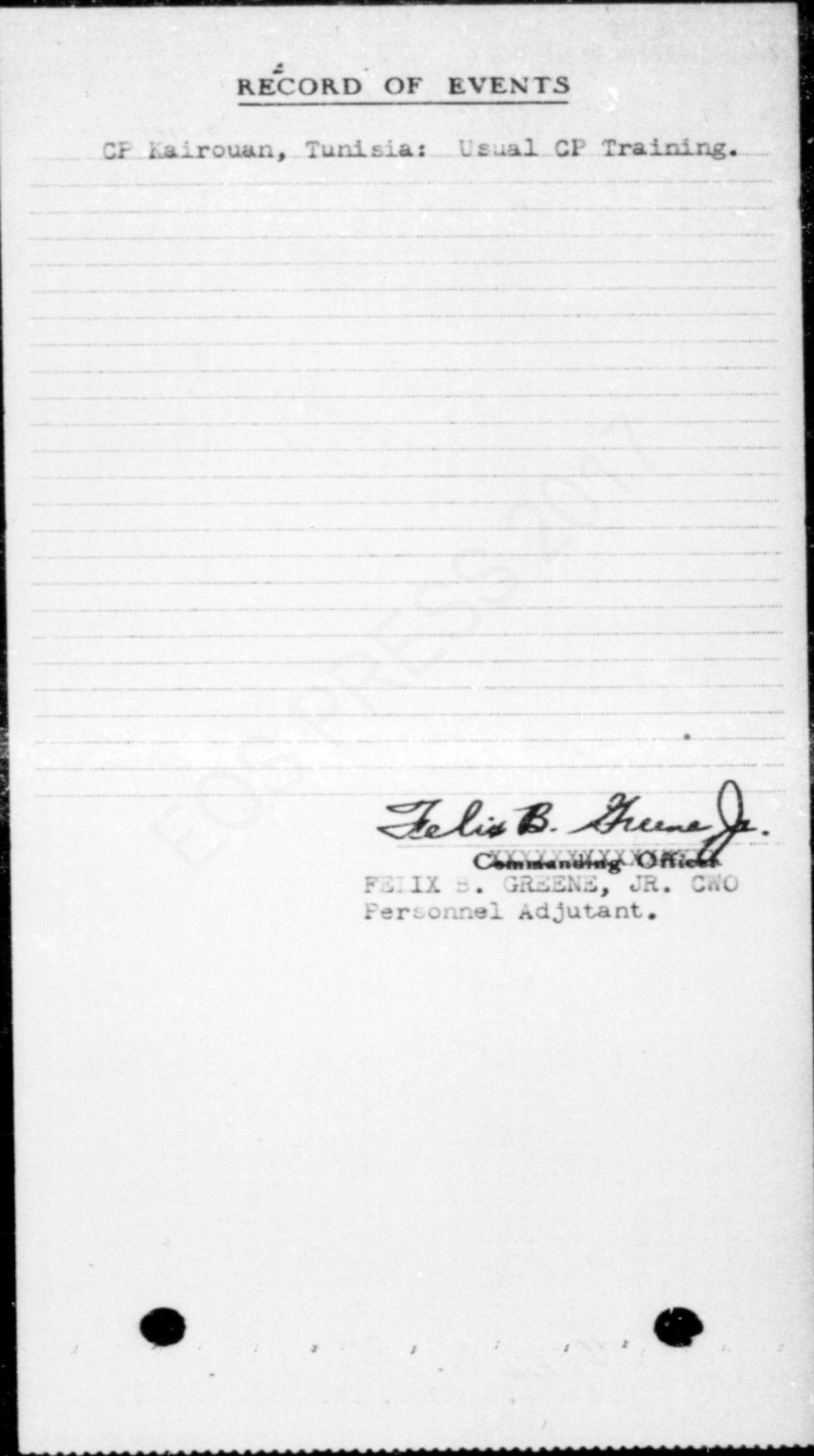

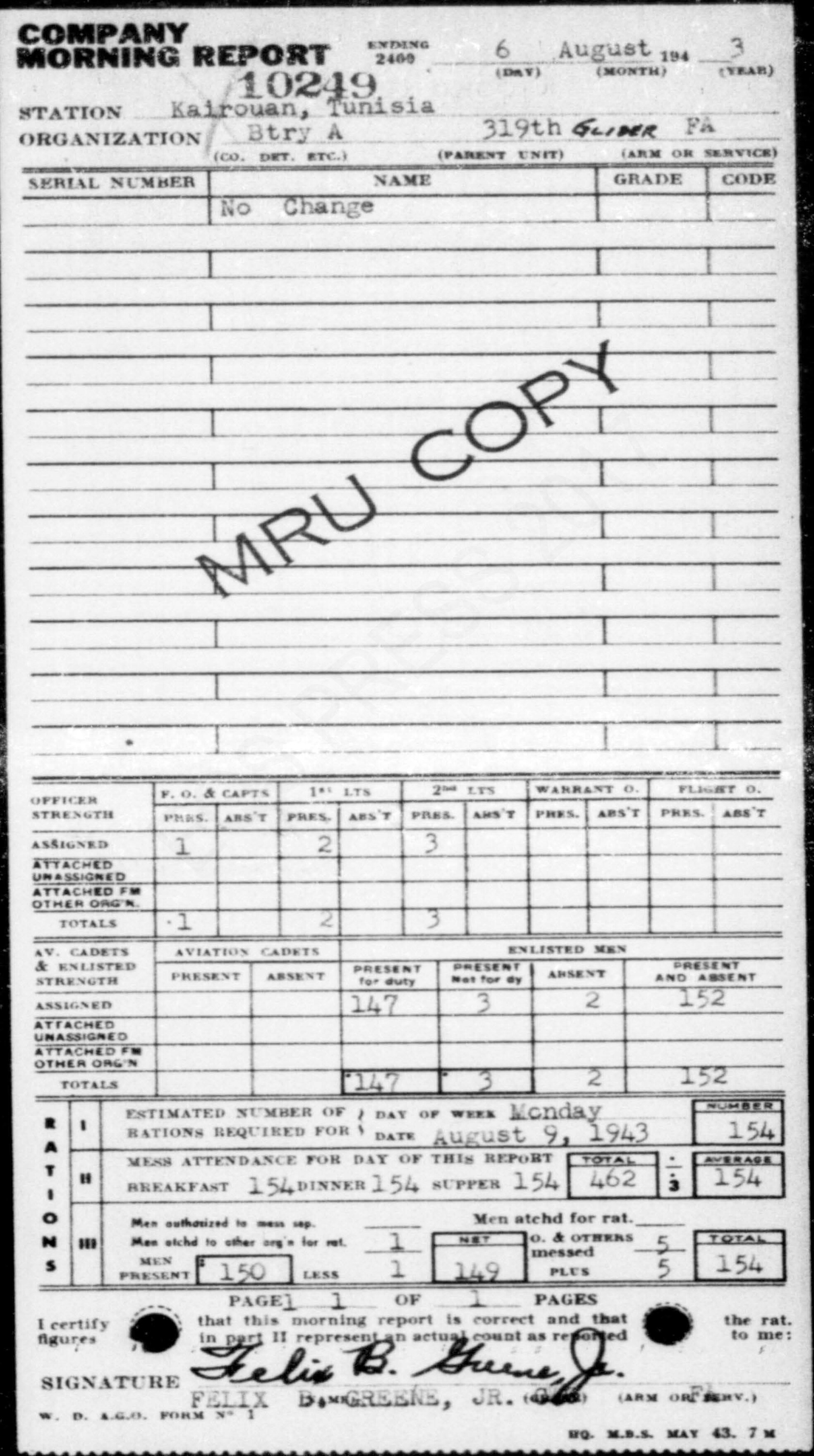

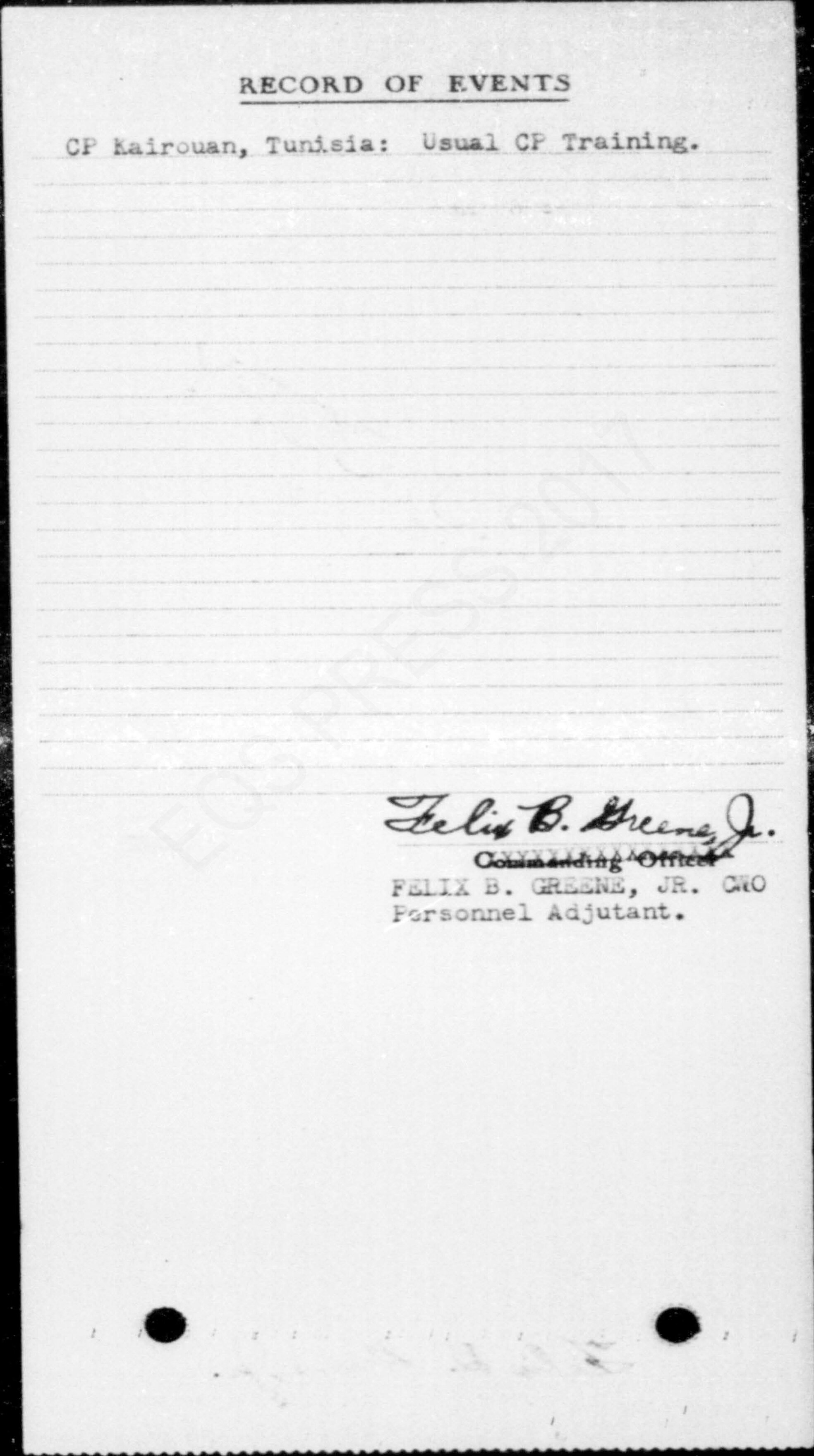

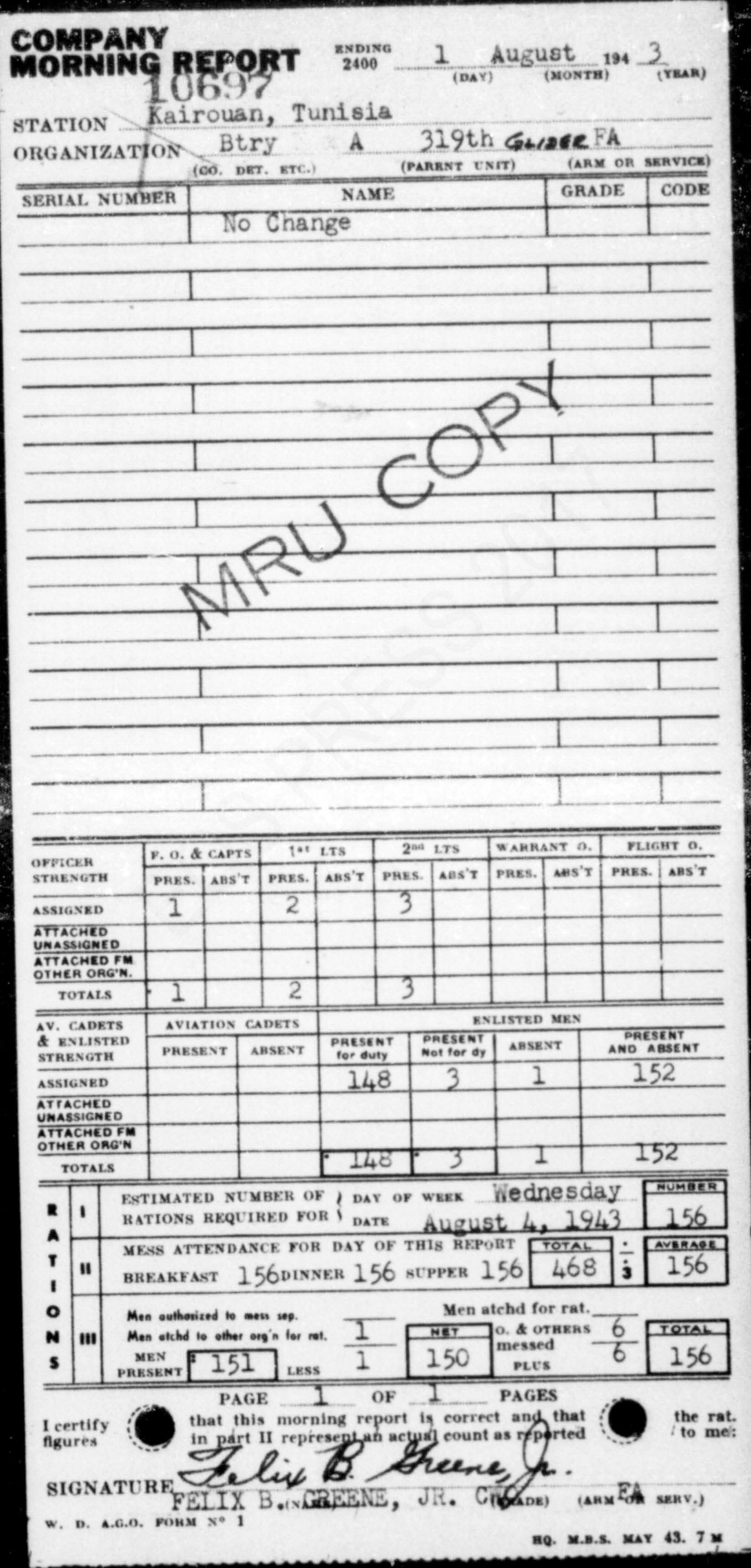

In reviewing the Morning Reports for that period, A-Battery boasted one Forward Observer, two 1st Lieutenants, three 2nd Lieutenants and 148 Enlisted Men. Training included compass and dismounted (on foot) marches as well as usual Command Post training.

82nd Airborne Review Parade Grounds, Oujda. General Eisenhower, General James Gavin and General Clark

Their time was not all training or digging fox holes. The men enjoyed playing softball, swimming in the Mediterranean, a glass of local vino or a beer while watching the movies “Aerial Gunner” and “Stranger in Town.” Some of the units even accumulated mascots. One had a baby goat, another a monkey, even a jackass.

Bob Hope: “I like Tunisia, it’s like Texas with Arabs”

On August 21, 1943, the 319th departed Kairouan, Tunisia for a new camp just north of Bizerte, Tunisia. A USO visit from Bob Hope and Frances Langford to entertain the troops sure was swell. “I like Tunisia, it’s like Texas with Arabs” joked Bob Hope.

Company Morning Reports were produced every morning by the individual Army units to record personnel matters. The Morning Reports for September, 1943, shows the battalion in Bizerte, Tunisia, packing and preparing for a forthcoming operation. On several occasions, the combat echelon departed by convoy for a possible mission, only to have it postponed. The plan at the time was an airborne invasion of Sicily, however, the 319th’s participation in Sicily was cancelled. A similar Operation, Giant II, a parachute, and glider drop at the Rome Airport was also cancelled. Their first combat mission would start as a boat ride crossing the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Amalfi coast of Italy.

Invasion of Southern Italy

The September 9, 1943, record of events reported the battery was loaded on boats and later joined a convoy for an unknown destination. The sea was calm until 12 enemy planes attacked, dropping bombs, and scoring a hit on one of the cruisers. The enemy aerial attack was driven off by our Air Force P-38s.

September 11th, 1943, the battery landed on the beach at Maiori, Italy, just before midnight. Morning Reports for September record the combat echelon on mission 8 miles northwest of Maiori, Italy. The war had begun for the 319th.