Salvatore “Ted” Covais

ASN: 12144557

SGT Salvatore Covais

Salvatore Covais registered for the draft on June 30, 1942. Born May 21,1923 he was from Brooklyn, New York. His place of employment is listed as Steward Toll Corporation located in Brooklyn, New York. This nineteen-year-old was 6-0, 185 pounds with a light complexion, blue eyes and blonde hair.

On September 20th, 1942, PVT Covais was inducted at Ft. Dix, New Jersey. He was sent directly to Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, and assigned to A-Battery of the 319th Glider Field Artillery Battalion, 82nd Airborne Division.

Along with fellow Glidermen, then PVT Covais traveled to North Africa in May 1943. Later promoted in rank to Sergeant, he fought in seven (7) battles and campaigns; Sicilian, Naples-Foggia, Normandy, Northern France, Ardennes, Rhineland, and Central Europe.

Company Morning Reports

Company Morning Reports were produced every morning by the individual Army units to record personnel matters. The following events (see below) were reported:

June 15, 1944, listed as wounded in action on June 6, 1944, and assigned to the hospital.

Furlough was granted on July 24, 1944 for 5 days to Birmingham, England beginning at 0600 hours.

From furlough to duty on July 29, 1944.

September 6, 1944, promoted from CPL to SGT.

For his service SGT Covais was awarded 6 Bronze Battle Stars, Bronze Arrowhead, Good Conduct Medal, the Belgian Fourragere, Presidential Unit Citation Badge with Oak Leaf Cluster, Victory Ribbon, European-African-Middle Eastern Theatre Ribbon and Purple Heart.

Biography

The following is a personal biography of Salvatore “Ted” Covais, including war time and personal photos, written by Joseph Covais, author of BATTERY.

Covais’ parents emigrated from Sicily in 1913. His mother and father operated several marginally successful businesses in Brooklyn and Peekskill, NY. The youngest of four brothers, Covais was self-conscious of his ethnic background and aspired to somehow escape from his Italian neighborhood and meld into what he perceived as the larger American culture.

“17 year old Ted Covais”

Civilian Conservation Corps

Young “Sal” seized his chance to get out of New York in 1938. That year he signed on for a six-month stint with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), during which he was stationed at Camp Cowiche, near Yakima, Washington. It was an eye-opening experience in the great outdoors. Mostly spent riding a jack-hammer and digging irrigation canals, records also indicate he took a typing class.

The CCC was administered through the US Army, with the work supervised by Regular Army officers and NCOs. Its members were clothed in a mixture of surplus WWI uniforms, items specifically produced for the CCC by the Quartermaster and personnel were housed in military-type barracks. Except for the shorter obligation and absence of weapons training, daily life in the CCC would be largely indistinguishable from service in the peace-time army.

Life in the CCC agreed with Covais, but not with his parents back home. On returning to Brooklyn, he joined the New York State Guard’s 14th Regiment. Sal felt he’d recaptured some of the military life he’d tasted in the CCC. At the time echoes of the 14th’s record during the Civil War were still strong. He was enthralled by the unit’s history and excelled in its drill sessions within the armory building.

Evidently his elan caught the notice of the regimental officers. Covais later recalled that he and one other young fellow from his company were selected to take a trip to the US Military Academy at West Point. Clearly they were being groomed as candidates for that institution. Though the trip was an honor, Sal felt intimidated by the class distinction he sensed. He was painfully aware of his lack of polished education and obvious immigrant’s-son demeanor. The tour left him feeling that he could never be part of such a distinguished society as the Corps of Cadets.

Sal’s time in the 14th Regiment came to an end when the State Guard, in anticipation of the entry of the United States into the European world war, was nationalized. Now under federal regulation, Covais, being not yet 18, was discharged. Shortly afterwards, the nation entered the war. Covais immediately volunteered as an air-raid warden, a job which involved checking that buckets of fire-smothering sand were placed in every stair-case landing, and that all windows were thoroughly covered in his district during designated black-outs.

Ft. Bragg - December 7, 1942

Entry to US Army

On June 30, 1942, Covais registered for United States draft. Those who knew him personally would recall Covais as a “Jack Armstrong, All-American Boy” who didn’t smoke, swear, drink, or miss Sunday Mass. So strong were his ideals that he would stand for the national anthem – even if alone and hearing it on the radio.

On September 20th, 1942, Covais was inducted at Ft. Dix, NJ, where he was given the usual round of inoculations and tests. His scores were above average. Sal thought service in one of the technical branches would keep him from the most dangerous front-line positions, and would involve more stimulating technical training than the infantry, so he volunteered and qualified for the artillery.

Covais was sent directly to Ft. Bragg, NC, where he was assigned to A-Battery of the 319th Glider Field Artillery Battalion. Still seeking to Americanize his identity, Covais told the other guys in the outfit his name was “Ted,” short for Theodore, thinking it was an anglicized version of Salvatore. Few members of the outfit ever knew him by any other name.

In early January 1943, Covais received a short furlough. He traveled to Brooklyn and eloped with his fiancé, Cathy Puleo. He and Cathy had been friendly since they were children. The Covais and Puleo families were long-time friends. Still, the families had strong reservations – what if Sal was killed in service? What if he comes back disabled or horribly disfigured? What then?

In spite of all these arguments, the two secretly took a train to Peekskill, NY, where Covais knew a Catholic priest who would perform the marriage ceremony. Their marriage certificate listed his given name as Theodore. They returned by train that night and he left for Ft. Bragg the following morning.

SGT Covais (left) and SGT Jesse Johnson with enemy artillery in Africa

Wartime Service

Ted’s wartime service is as one with the story of the 319th. He landed at Casablanca, Morocco, along with the rest of the division in May 1943. Promoted to corporal, he trained as an assistant to officers serving as forward observers. As such, he learned about spotting targets, plotting the map co-ordinates of those targets, and the procedures of fire direction. Though he remarked in later years that he was always a member of A-Battery, his close relationship with C-Battery officers, Lt. Sartain and Captain Manning, as well as photographic evidence, suggests he was probably part of the short-lived C-Battery which existed from the summer of 1943 until early 1944.

Covais participated in combat at Chiunzi Pass, a mountainous terrain overlooking the beach village of Maiori, Italy. During the combat at and around “88 pass” he had numerous close calls; one of which he related decades later. “I remember one day I was up there at the forward observation post,” he said. “I had my binoculars on, viewing the enemy, and I heard shots being fired from behind. I heard this firing. The Hermann Goering Division got behind our lines. So, I had to make a quick decision. I was sticking out there like a sore thumb. I was digging my trench with my shovel but I couldn’t get all the way down the way I should. I figured if they shoot my head off I’m dead, if they shoot my feet off I’ve got a chance to live. So, I put my butt-side down into the hole with my feet sticking up in the air, like that, and I put my head below the level of the ground, and I thought, well, I’m not gonna move my feet, so maybe I won’t be noticed. That’s how I survived that day.”

Combat at the Volturno River bridge in Cancello e Arnone followed, then several weeks of occupation duty in Naples.

Late in 1943, the 319th relocated to Northern Ireland then to a new base-camp at Papillon Hall, a 17th century manor and estate just outside Lubenham, England.

D-Day - Mission Elmira

By the time of the D-Day invasion, Ted was in A-Battery. On the night of June 6th, when the 319th glided in as part of Mission “Elmira,” about one third of the outfit became casualties. From his description, it seems apparent Covais’ glider was among those which set off demolition charges rigged to poles where the Germans anticipated gliders might attempt to land. It wasn’t until these obstructions were described to him decades later that he was aware of this, but the nature of the glider obstructions fit precisely with his recollection of tremendous explosions blowing off the wings and top of the glider a moment before it slammed flat to the ground.

Covais was scuffed up, with a head-wound which, while not serious, bled profusely. In the confusion which followed, his principal memories were of dodging machine-gun fire until he and others reached the relative safety of a hedgerow. When one Lieutenant told him to retrieve his lost binoculars, CPL Covais declined, explaining that everyone needed to stay put for the present, and that if he, the lieutenant, needed his binoculars immediately he’d have to get them himself.

The directive was that all head-wounds were to be evacuated. Accordingly, Covais was taken to Utah beach and sent back to England on June 8th. After a stay in the hospital he returned to the 319th base camp at Papillon Hall, where he was put in charge of a squad detailed to separate out the barracks bags of those killed in the Normandy invasion.

On September 6, 1944, Ted was promoted to Sergeant and in addition to the ordinary duties of a reconnaissance NCO, given responsibility for the optical equipment and maps for the forward observation teams of A-Battery.

SGT Covais with his “Thompson” in Bemmel, Holland November 5, 1944

Operation Holland

Compared to Normandy, the airborne invasion of Holland was an easy landing from an aviation perspective, but the combat which followed was intense. By this point in his service, Covais was among the more experienced members of the forward observation teams, which he now sometimes was placed in charge of, calling in fire-missions on enemy positions or troops.

With pride, Covais particularly remembered serving alongside Lt. Col. Louis Mendez of the 3rd Battalion, 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment. “This guy Mendez, he was fearless, fearless,” Covais recalled a half century later. “He’d walk around out in the open with machinegun bullets flying all around him, and as his artillery liaison I’d have to be right there with him. He’d say, ‘Sergeant, I want fire here - fire there.’ So as his artillery liaison, I’d have to call it in and direct the fire mission.”

Battle of the Bulge

Along with the rest of the 82nd, Covais re-entered combat in the Battle of the Bulge from mid-December, 1944 to late winter of 1945. He remembered it as a grueling experience – a crucible which brought him to the very limits of his endurance. Covais remembered one night this way, “I was so miserable that I, just speaking frankly, I was so sick of the war, so sick of everything. I was freezing. I couldn’t even button up my coat or work my hands. … I didn’t care if the Germans shot me, captured me, I just wanted to end it, and the thought crossed my mind that maybe it’s a good time for me to end it all. Take and put the gun, my .45 automatic to my head. I was so disgusted … I used to think I would never do that or think about that, but I came close to it. The only thing that saved me, was this guy had a jeep … I think he was Col. Mendez’s driver. In the jeep he had a little Coleman stove… He was keeping warm with that, and he invited me in to sit next to him, and I did, and I was saved.… I felt the life come back into me. Instead of thinking about death I was thinking about staying alive.” A few weeks later, during a change of position, Covais declined a ride from the same jeep driver who’d recently saved his life. “The jeep driver said to me, come on, get in! he saw I was cold. I looked at him and I thought to myself, you know, there’s snow out there. You cannot see if there are mines. It could be the roads are not mined, but he’s going across open fields. So, I said to him, no thank you, I’d rather walk. So, I walked ahead of the jeep. The jeep is going slow, and it was just about five minutes later up in to the field I hear this big explosion, kaboom! We all hit the ground. I turned around and I saw the jeep back there had hit a mine. The same jeep. I went back, and there was a guy sitting in the very seat that I was supposed to be sitting in with a big hole in his temple, and he did not make it. He did not make it.”

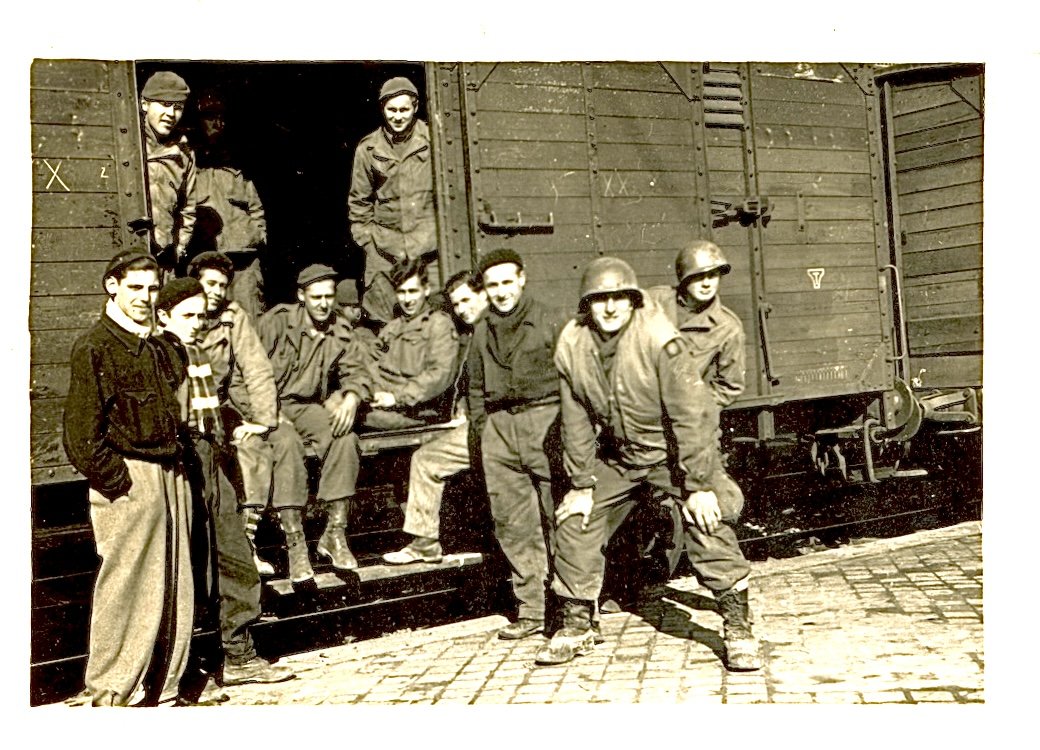

Photos below (L-R) Artillerymen amidst "dragons teeth" January 1945 - SGT Covais (L) and Roland Gruebling - Becco, Belgium January 1945 - Back from “The Bulge” SGT Covais (Front-R)

Certificate of a qualified parachutist

(SGT Covais also appeared in the A-Battery group photo taken June 20, 1945 in Epinal, France.)

In March 1945, during a period of rest and refitting, Covais became qualified as a paratrooper, believing he stood a better chance of surviving a combat drop by parachute than another crash landing in a glider. Though the chance to prove those calculations never came about, the distinction he felt as part of an airborne brotherhood remained a tremendous source of pride.

Sal Covais, Roland Gruebling, Wilbert Gearing (L-R) and “ booby trapped tank” - Cologne Catherdal in April 1945

The Siege of Cologne, Germany

With the 319th, Covais participated in the siege of Cologne, Germany. For several days he had an observation post established on the roof of the Ford Motor Works, overlooking the Rhine River. Surrounded by massive destruction, the Ford factory was strangely intact. By this point in the war, he had become hardened and cynical. Behaviors the idealistic teenager of the CCC would have never condoned, now seemed justified. In one of the Ford offices, he found a typewriter, which he shipped home, along with other household items taken from abandoned homes and apartments. “I always wanted a typewriter,” he said years later. “I confiscated that. I did some looting maybe; you might consider it. I did manage to get some silverware that was in a house that was abandoned. It was not proper. I don’t feel right in my spirit about it…. When you want something you don’t care how other people feel about that. I felt more like you robbed all these people of their masterpieces, of museum pieces, paintings and artwork and statuary and all that. Millions! ……I felt I had the right, maybe not morally, but I had the right to do it. I wanted to show them who’s the real master. I’m sorry about all this, all these things.”

SGT Covais posing with 155 mm artillery

From Cologne the 319th, with SGT Covais in tow, went across northern Germany, over the Elbe River. German resistance was disintegrating. There were massive surrenders. The prisoners brought with them thousands of civilian refugees fleeing the Russians. They told of terrible atrocities committed by the Red Army and begged the Americans to join with them to fight the Soviets – because communism was the real enemy. Covais agreed that the Soviet Union was an enemy which would need to be fought, but believed Nazism had to be obliterated first. As he later put it, “At the time I thought we should take Berlin, then keep going to Moscow.”

Wobbelin Concentration Camp

Covais had respect for the German soldiers he fought, and an element of compassion for the German civilians, but when he saw the horrors of the Wobbelin concentration camp he realized that what he’d been fighting was unmitigated evil, perpetrated on a scale which was difficult to comprehend.

For the rest of his life, Covais was never able to discuss what he saw at Wobbelin without tears. “They had all these prisoners,” he said. “They were just skin and bones, oh, emaciated completely. Skin and bones. I remember there were bodies, naked bodies, men on the ground. Maybe about four, five feet high. On the other side of the road, they had a concentration camp for women.” Covais took a moment more to reflect, then added, “Annihilation, I guess is the word to use, because everything is annihilated. Everything is destroyed! Real estate, property damage into the millions, into the millions. Row upon row of homes destroyed. Cities destroyed. Completely! Obliterated! For what? To what purpose or end? My God.”

Sgt. Covais was discharged on September 19th, 1945, having served one day short of three years.

Post-War Years

Reunited with his wife, Covais tried to resume the married life he’d never really started, but things were different, mostly he was different. No one in civilian life was willing to call him “Ted,” so after a few months he gave up on it and reverted back to “Sal.” Now the all-American boy was a chain smoker, a social drinker, and was not beyond occasional small-caliber swearing. After several months the nightmares stopped, but, having lost his faith in both God and men, he couldn’t bring himself to go to church.

Covais discovered civilian life carried with it a plethora of mundane responsibilities. It was quite a difference from the army, where meals, housing, employment, purpose, and even adventure were all guaranteed in the course of a day. His first jobs were all manual labor, but in time he gravitated to selling insurance, a field in which he stayed for about twenty years.

Sal and Cathy Covais had three children: Camille, Antionette, and Joseph.

After the war, Covais kept in intermittent contact with Major John Manning and Captain Charles Sartain, but it was his friendship with Roland Gruebling which remained the most enduring of all. Covais and “the Grebe” made several visits over the decades to each others’ homes and innumerable phone calls. One day in 2002, Covais arose with his old buddy on his mind. Unable to shake the distraction, he called Greubling’s number in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, only to discover that Roland had passed away only a few hours before.

Covais was also an occasional attendee at the 82d Airborne’s annual reunions at Ft. Bragg– particularly in his later years. On one occasion in the 1990s he noticed another old-timer wearing the distinctive unit insignia of the 319th. It turned out to be Mahlon Sebring, one of Covais buddies from the A-Battery Signal section. As the two clasped hands for the first time in half a century, the years slipped away.

The dream of moving to the far west, or at least far from New York City, never entirely left Covais. In the 1950s and 60s, he relocated twice, each time further out on Long Island. Covais explored moving his family to California or the pacific Northwest. It was the dream of returning to the unencumbered west which pulled him, but escaping the orbit of relations in New York proved more than he could manage. Finally, Florida became the compromise on which he and his wife could agree. In 1972, he relocated to Sarasota, Florida, where he died on June 2, 2004, of congestive heart failure. His funeral service was held on June 6th, the 60th anniversary of the Normandy invasion. Sgt. Covais was buried in uniform, with his ribbons and decorations.

Joseph Covais, author of BATTERY, recalling his father and the wartime experiences

In the final decade of his life, Covais made it a practice to scan obituaries for the deaths of World War II airborne troopers – 82nd, 101st, 17th – it didn’t matter. He would attend their funeral service, making no effort to introduce himself to survivors, but rather to bare silent witness to his airborne brothers with one final salute.

It was a long journey from the idealistic teenager of the CCC to the disillusioned veterans who couldn’t bring himself to attend church, and finally, in the 1980s to his renewed faith in God. Yet, even then, Covais was never able to reflect on his wartime experiences without considerable emotion. When asked if he’d always been this way, his answer was, “No, only since the war. I think I realized there were things in life worth crying over.”

Salvatore Covais, 81, died June 2, 2004.

God bless this hero.