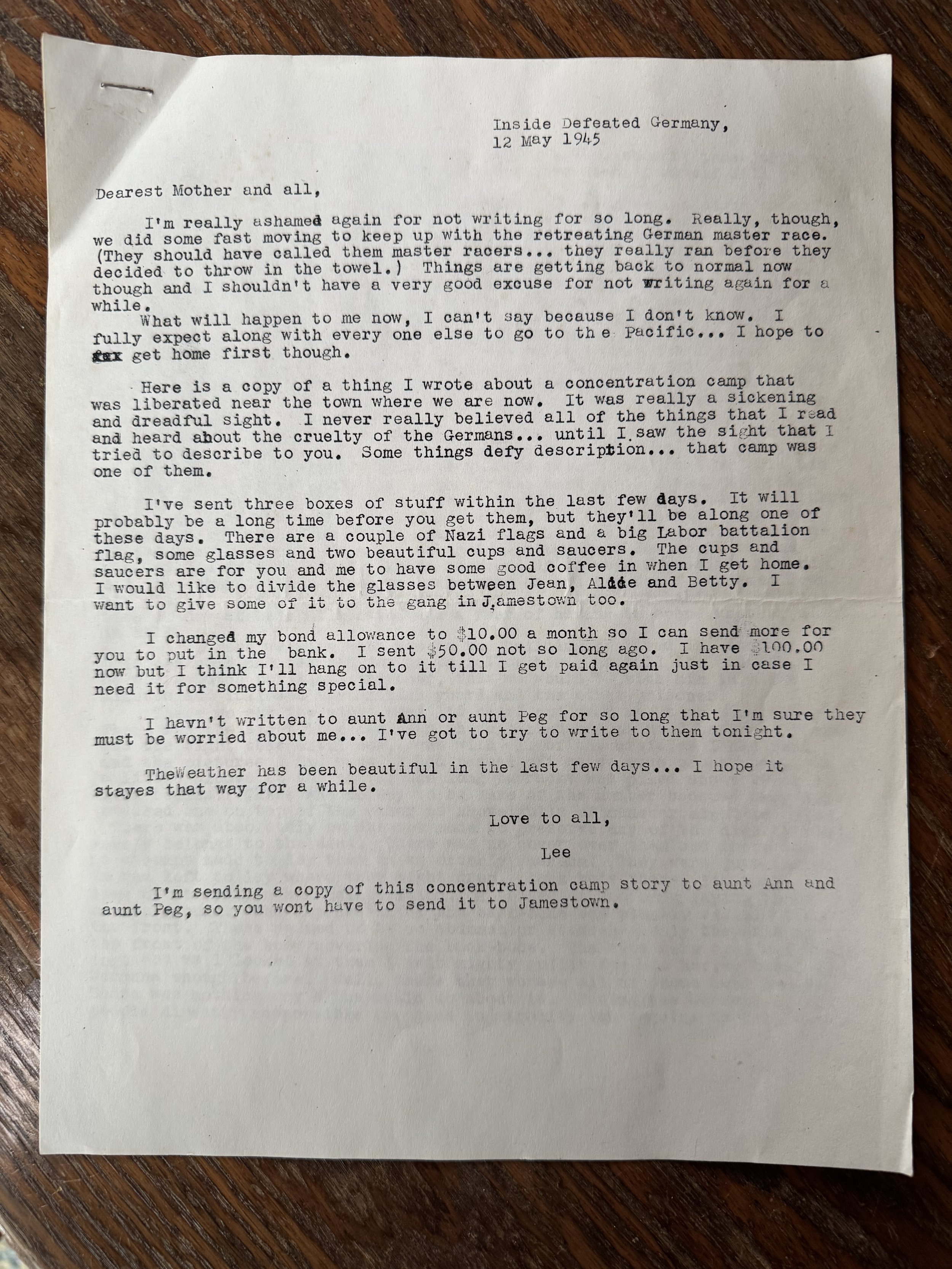

Lee Patterson

ASN:34794884

307th Airborne Medical Company 82nd Airborne

Enlisted 1943, served with the 307th Airborne Medical, rank Tec 5. He was present at Wobbelin Camp in May 1945, see letter below. Reenlisted with an M.P. Platoon 82nd Airborne, October 1945, while stationed in Germany. Separated from the service September 4, 1948.

slide show, side controls to next image

“Inside defeated Germany, 12 May 1945

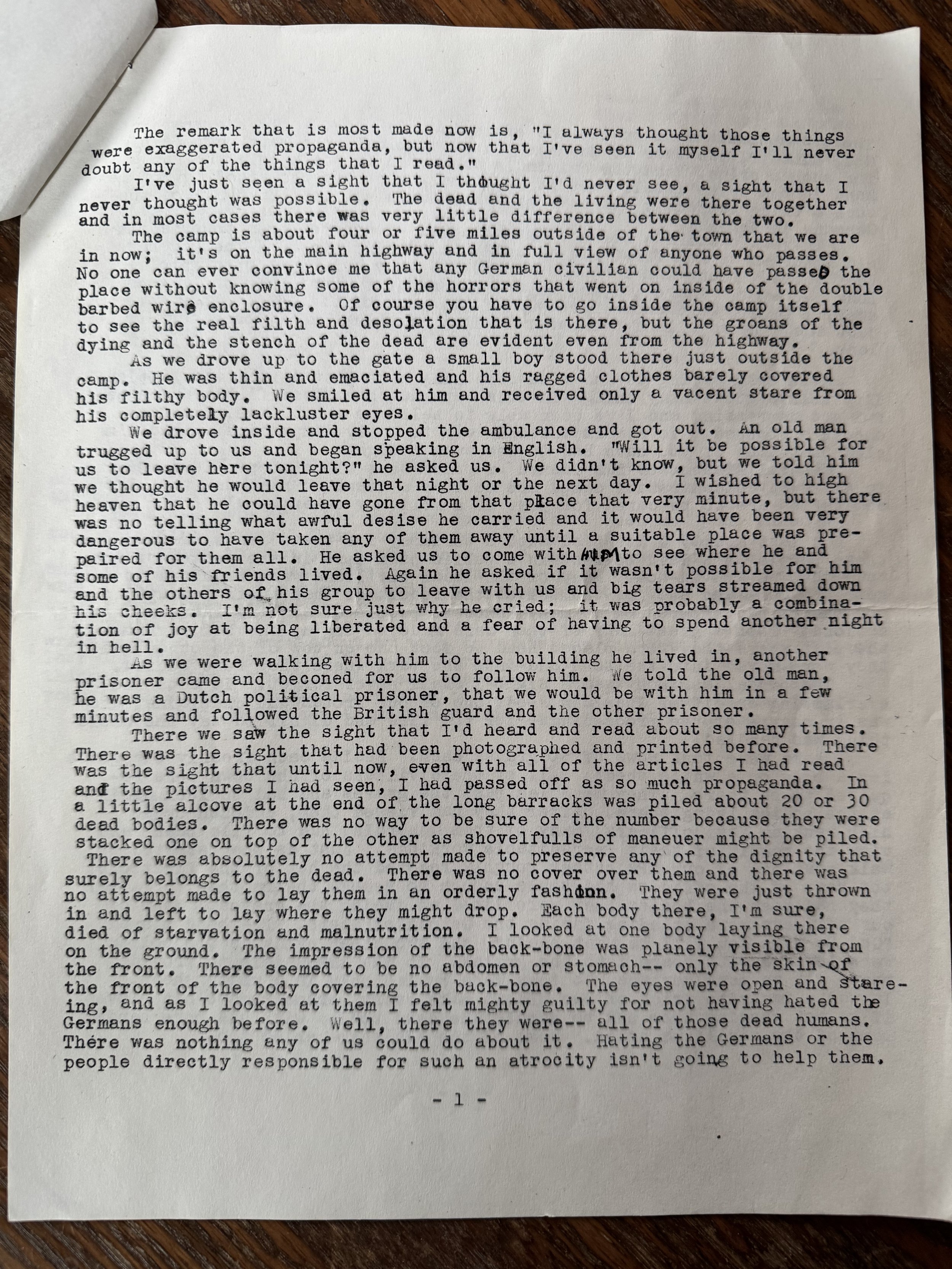

The remark that is most made now is, “I always thought those things were exaggerated propaganda, but now that I’ve seen it myself, I’ll never doubt any of the things that I read.”

I’ve just seen a sight that I thought I’d never see, a sight that I never thought was possible. The dead and the living were there together, and in most cases, there was very little difference between the two.

The camp is about four or five miles outside of the town that we are in now; it’s on the main highway and in full view of anyone who passes, places without knowing some of the horrors that went on inside of the double barbed wire enclosure. Of course, you have to go inside the camp itself to see the real filth and desolation that is there, but the groans of the dying and the stench of the dead are evident even from the highway.

As we drove up to the gate, a small boy stood there just outside the camp. He was thin and emaciated and his ragged clothes barely covered his filthy body. We smiled at him and received only a vacant stare from his completely lackluster eyes.

We drove inside and stopped the ambulance and got out. An old man trudged up to us and began speaking in English. “Will it be possible for us to leave here tonight?” he asked us. We didn’t know, but we told him we thought he would leave that night or the next day. I wished to high heaven that he could have gone from that place that very minute, but there was no telling what awful disease he carried and it would have been very dangerous to have taken any of them away until a suitable place was prepared for them all. He asked us to come with him to see where he and some of his friends lived. Again, he asked if it wasn’t possible for him and the others of his group to leave with us and big tears streamed down his cheeks. I’m not sure just why he cried; it was probably a combination of joy at being liberated and fear of having to spend another night in hell.

As we were walking with him to the building he lived in, another prisoner came and beckoned for us to follow him. We told the old man, he was a Dutch political prisoner, that we would be with him in a few minutes and followed the British guard and the other prisoner.

There we saw the sight that I’d heard and read about so many times. There was the sight that had been photographed and printed before. There was the sight that until now, even with all of the articles I had read and the pictures I had seen, I had passed off as so much propaganda. In a little alcove at the end of the long barracks was piled about 20 or 30 dead bodies. There was no way to be sure of the number, because they were stacked one on top of the other as shovelfuls of manure might be piled.

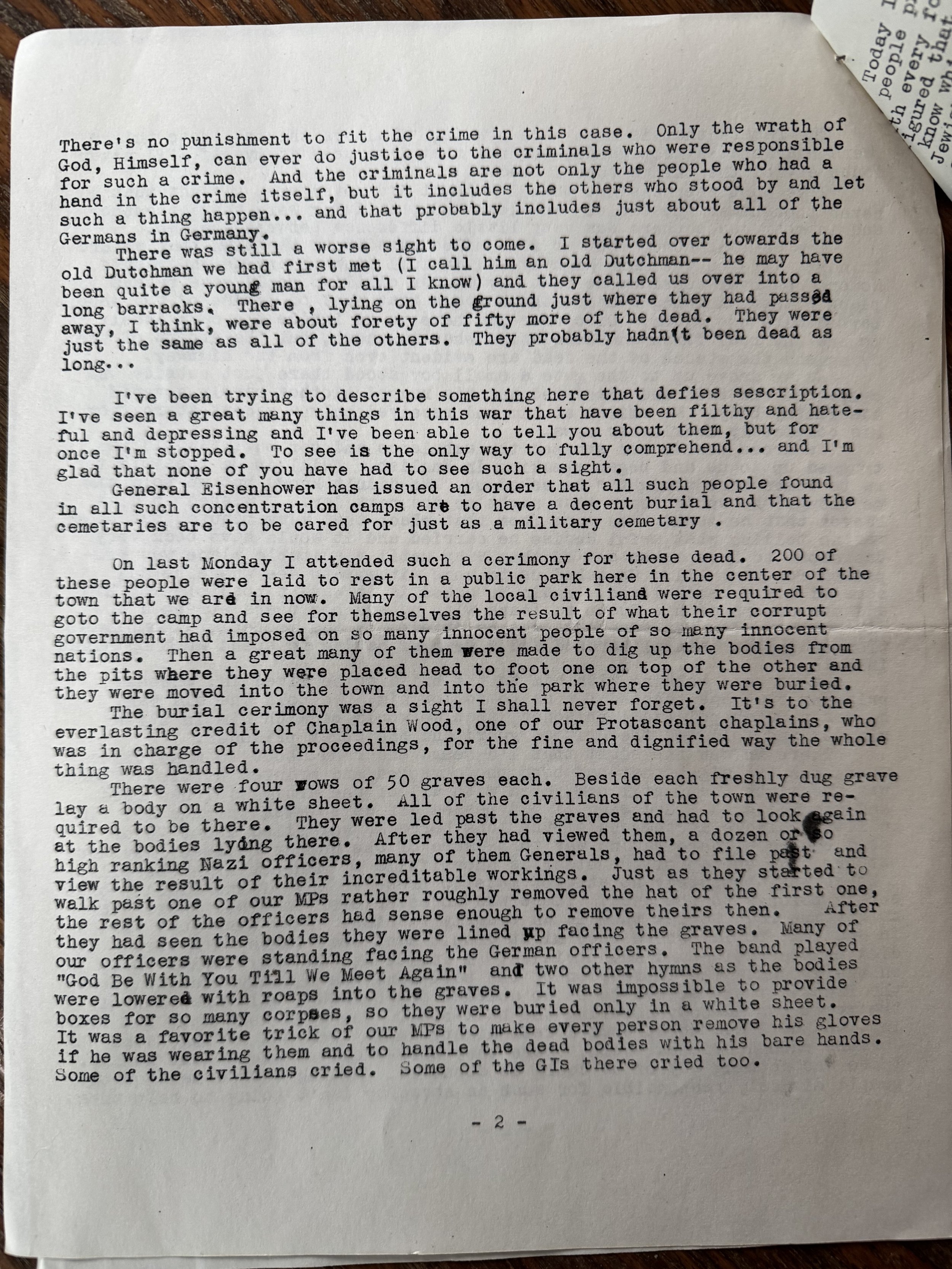

There was absolutely no attempt made to preserve any of the dignity that surely belongs to the dead. There was no cover over them and there was no attempt made to lay them in an orderly fashion. They were just thrown in and left to lay where they might drop. Each body there, I’m sure, died of starvation and malnutrition. I looked at one body lying there on the ground. The impression of the backbone was plainly visible from the front. There seemed to be no abdomen or stomach – only the skin of the front of the body covering the backbone. The eyes were open and staring, and as I looked at them, I felt mighty guilty for not having hated the Germans enough before. Well, there they were – all of those dead humans. There was nothing any of us could do about it. Hating the Germans or the people directly responsible for such an atrocity isn’t going to help them. There’s no punishment to fit the crime in this case. Only the wrath of God, himself, can ever do justice to the criminals who were responsible for such a crime. And the criminals are not only the people who had a hand in the crime itself, but it includes the others who stood by and let such a thing happen…and that probably includes just about all of the Germans in Germany.

There was still a worse sight to come. I started over towards the old Dutchman we had first met (I call him an old Dutchman—he may have been quite a young man for all I know) and they called us over into a long barracks. There, lying on the ground just where they had passed away, I think, were about 40 or 50 more of the dead. They were just the same as all of the others. They probably hadn’t been dead as long…

I’ve been trying to describe something here that defies description. I’ve seen a great many things in this war that have been filthy and hateful and depressing and I’ve been able to tell you about them, but for once I’m stopped. To see is the only way to fully comprehend…and I’m glad that none of you have had to see such a sight.

General Eisenhower has issued an order that all such people found in all such concentration camps are to have a decent burial, and that the cemeteries are to be cared for just as a military cemetery.

On last Monday, I attended such a ceremony for these dead. Two hundred of these people were laid to rest in a public park here in the center of the town that we are in now. Many of the local civilians were required to go to the camp and see for themselves the result of what their corrupt government had imposed on so many innocent people of so many innocent nations. Then a great many of them were made to dig up the bodies from the pits where they were placed, head to foot, one on top of another and they were moved into the town and into the park where they were buried.

The burial ceremony was a sight I shall never forget. It’s to the everlasting credit of Chaplain Wood, one of our Protestant Chaplains, who was in charge of the proceedings, for the fine and dignified way the whole thing was handled.

There were four rows of 50 graves each. Beside each freshly dug grave lay a body on a white sheet. All of the civilians of the town were required to be there. They were led past the graves and had to look again at the bodies lying there. After they had viewed them, a dozen or so high ranking Nazi officers, many of them Generals, had to file past and view the result of their incredible workings. Just as they started to walk past, one of our MPs, rather roughly, removed the hat of the first one, the rest of the officers had sense enough to remove theirs then. After they had seen the bodies, they were lined up facing the graves. Many of our officers were standing facing the German officers. The band played “God Be With You Till We Meet Again” and two other hymns as the bodies were lowered with ropes into the graves. It was impossible to provide boxes for so many corpses, so they were buried only in a white sheet. It was a favorite trick of our MPs to make every person remove his gloves, if he was wearing them, and to handle the dead bodies with his bare hands. Some of the civilians cried. Some of the GIs there cried, too.

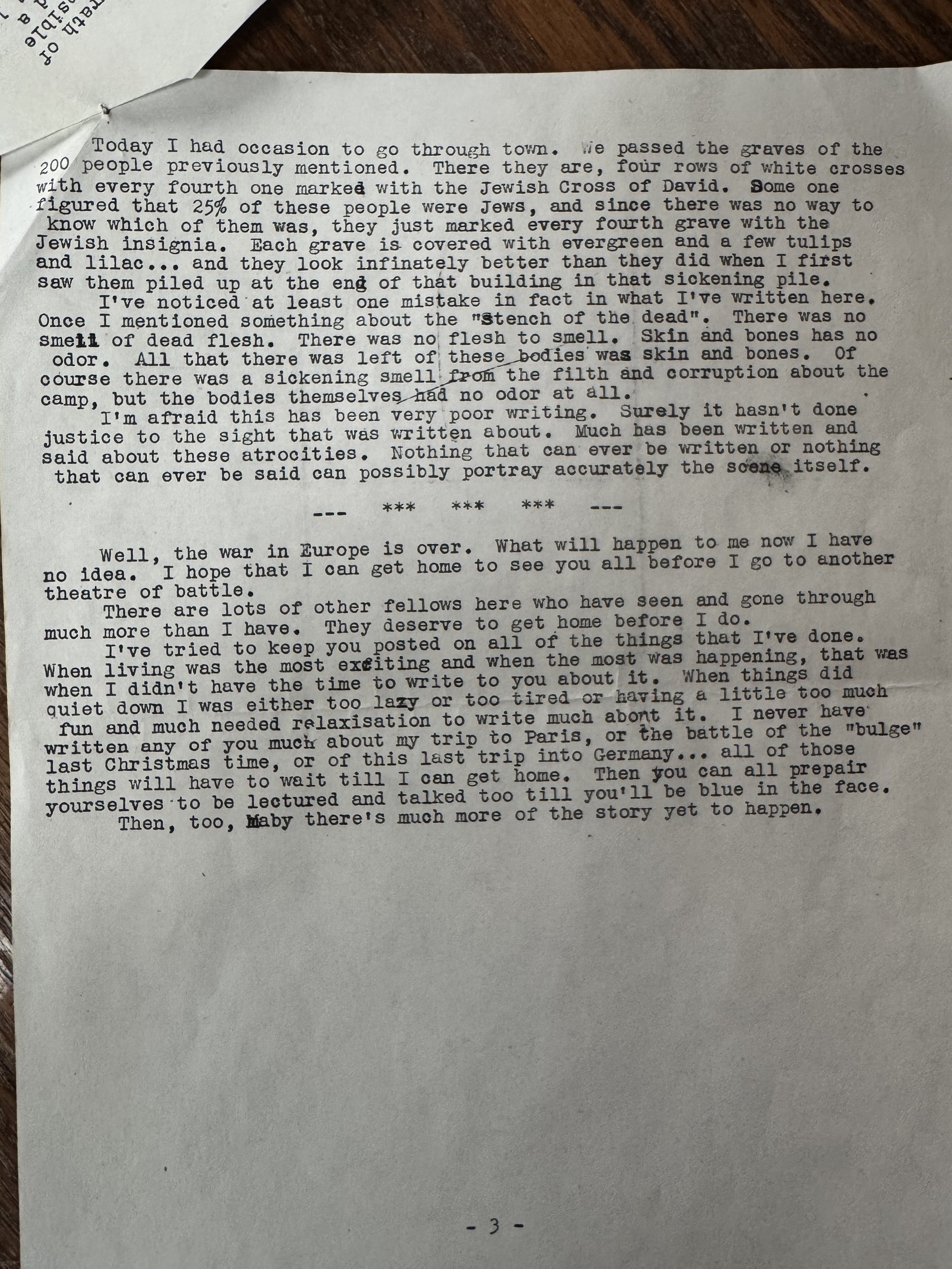

Today, I had occasion to go through town. We passed the graves of the two hundred people previously mentioned. There they are, four rows of white crosses with every fourth one marked with the Jewish Star of David. Someone figured that 25% of these people were Jews, and since there was no way to know which of them was, they just marked every fourth grave with the Jewish insignia. Each grave is covered with evergreen and a few tulips and lilac…and they look infinitely better than they did when I first saw them piled up at the end of that building in that sickening pile.

I’ve noticed at least one mistake in fact in what I’ve written here. Once I mentioned something about the “stench of the dead”. There was no smell of dead flesh. There was no flesh to smell. Skin and bones has no odor. All that there was left of these bodies was skin and bones. Of course, there was a sickening smell from the filth and corruption about the camp, but the bodies themselves had no odor at all.

I’m afraid this has been very poor writing. Surely, it hasn’t done justice to the sight that was written about. Much has been written and said about these atrocities. Nothing that can ever be written or nothing that can ever be said can possibly portray accurately the scene itself.

--- *** *** *** ---

Well, the war in Europe is over. What will happen to me now, I have no idea. I hope that I can get home to see you all before I go to another theatre of battle.

There are lots of other fellows here who have seen and gone through much more than I have. They deserve to get home before I do.

I’ve tried to keep you posted on all of the things that I’ve done. When living was the most exciting and when the most was happening, that was when I didn’t have the time to write to you about it. When things did quiet down, I was either too lazy or too tired or having a little too much fun and much needed relaxation to write much about it. I never have written any of you much about my trip to Paris or the “Battle of the Bulge” last Christmas time, or of this last trip into Germany…all of those things will have to wait till I can get home. Then you can all prepare yourselves to be lectured and talked to till you’ll be blue in the face.

Then, too, maybe there’s much more of the story yet to happen.

Letters to Home

France

22 November 1944

Dearest Mother and All,

Now that one phase of my military career has ended I think it’s high time that I make a report. So here is a complete as possible report of what happened while I was in Holland…at least, here is as much of it as is left after censorship. There shouldn’t be too much of it censored, though, because I’ve said nothing here that hasn’t already been on the radio and in all of the newspapers time and again.

Well, here goes: (When I sat down to write this letter one of the things I promised to do was to go straight through with the story and have none of these annoying little parenthetical remarks that are—or is—one of my bad habits. Just as I began to write though one of the fellows came in and asked if I’d seen a patient wandering about. They had a movie here earlier tonight and the fellow who came in said that he hadn’t seen the patient since it let out. That’s the way it goes all of the time. Never a dull moment for a medic. But I suppose the dull moments of the fellows who shoot the guns rather than the hypodermic needles are few and far between too.)….But now to try to go on…

We were all set to go a couple of days before we really took off. “Sweating it out” is the way it’s usually expressed in the army—those days of waiting before a combat mission. Because I’d never been in combat before I looked upon it as more or less of a lark. And besides I was overjoyed at being able to come at all, because I almost had to stay behind. You remember how I was forever bitching about that clerical job that I had in England a couple of months ago. I almost had to stay behind and continue with that, but I finally managed to talk the CO and the first sergeant of my company and the Captain of my detachment into letting me go. (A couple of times in the days that followed I wondered why I had been such a fool—but, now that it’s over, I’m mighty glad that it all came out the way that it did.)

To go flying off the ground in a glider isn’t much different than to go flying off in an airplane—except for the fact that you realize that you’re in a glider, a craft of light construction and lacking any kind of motor. First the big tow plane warmed up—you could feel the power rushing back from its mammoth motor and its great propellers. Then you watch out the little window and your eyes suddenly fix themselves on the white nylon tow-rope. The rope is curled up in great folds between the towplane and the glider. Then the rope begins to unfold, the plane is moving; the rope becomes taunt, there’s a little jerk and the glider begins to move. Soon you’re in the air… Good Lord, how I’m going on about this take off… I think I’d better get some sleep…maybe I won’t feel quite so dramatic the next time I get at this story.

26 November 1944

…I might mention that because the glider is so light and because the airplane is so heavy, the glider usually, if not always, leaves the ground before the plane does.

I just thought I’d mention that. Let’s see now, I’ve got myself off the ground. And by the grace of God and the skill of the pilot we’re safely on our way. It’s a beautiful sight to see the patterned fields below as you go flying along, and the weather was at its best; and even though we weren’t exactly on a sightseeing tour, I did enjoy the view a lot. I felt kind of a lump in my throat as we sighted the water (I guess I’d better not mention what body of water) and as we neared the other side the lump grew bigger. When we sighted the other side the excitement became almost unbearable…it was the strangest combination of fear, anticipation, false bravo and the little bit of real guts that I do give myself credit for having had that I have ever known. On the way one of the other fellows got a little sick (he was visibly sick; I guess the rest of us felt as badly as he did but were lucky enough to be able to hide it.) Always the faithful medic, I got up to help him. After he was through vomiting, I gave him my piece of parachute silk I was using for a muffler and which I prized very highly to clean his face; then I wetted it with cold water from my canteen for him to swab his forehead. I felt very sad and yet a little proud when I had to throw that scarf away.

Although our landing was far from uneventful, I’d better not get involved in a lengthy description of that either. I might say that while some of the gliders landed a little roughly (and that’s a masterpiece of understatement if ever there was one) ours made a very smooth one and all we got was a little of the Holland soil in our eyes and mouths. What happened in the next half hour will have to wait for telling till I can see you at home.

We were standing around a little village waiting further orders when one of my friends, name O’ George, called me over behind a big tree to see something. There sprawled out on the ground in a sickly little heap was the first dead German I was to see. If I still felt like I did not so very long ago I’d have felt sorry for him, but I had seen other men who weren’t German sprawled on the ground in the same way, so I felt a little viciously happy as I looked down at his powerless body. (And I don’t see why that can’t go under the heading of personal experience which the censor has told us we can relate now.)

Well, we got our orders to set up our aid station, so up went our tents with the big red crosses on them. They were out in the middle of an open field plainly visible for everyone to see. They were as plain to the German planes as they were to our own. And that brings up a couple of more stories that will have to wait for telling until I get home. Then we started digging fox holes (they weren’t really fox holes—they were slit trenches. You can only sit or stand in a fox hole, but you can lie down and stretch out in a slit trench) and I thought surely that with shells landing pretty close I’d be able to dig one in record time, but mine was one of the last ones done.

I don’t know just what satisfaction a soldier gets out of shooting one of the enemy and of seeing him fall dead or out of working order in front of him, but I imagine it might be a little like the satisfaction a medic gets out of patching up one wounded. I didn’t do very much actual patching, I was a litter bearer most of the time, but every little thing I did do made me feel good inside…and it was that feeling more than anything else, I guess, that made me glad that I was where I was instead of back in England behind a desk where I almost had to stay. We all worked damned hard and there wasn’t much time to be scared, but we’d have all worked harder yet if we’d have had to. It wasn’t the kind of job that you’d quit in the middle of and take a rest, but the kind that you felt you had to go on and on doing till you dropped—and some of us almost did drop.

But that only lasted for a few days and then we got into the place I’ve told you about in previous letters. And, boy oh boy, were those bathtubs swell and were those beds comfortable when we did get them. I don’t ever expect to appreciate those two items quite as much again as I did then.

(It’s getting late and I have to get up early in the morning, so…)

28 November 1944

I haven’t written to any of you for several days, so what I should do is to forget about the dim, dark past and leave you hear a little about the present, which I think I’ll do right now.

Just bear with ne and I may be in the States to read this letter to you myself by the time it gets to you.

29 November 1944

Now I’m coming to a part that I want to tell you, but I’ve got to be darned careful what I say. I suppose it’s best that I don’t tell you how much time I actually spent on the front lines. It wasn’t so very long—not nearly as long as some of the fellows I know who are in some of the ground forces, the infantry and such other outfits as that. I’ll tell you about one day and night that I was there and that will do the trick, I guess.

We had worked all night and had just been in bed about a half-hour, when the sergeant came into our room and told us that they needed two litter squads at the front. I was too sleepy to be scared—just sleepy enough to be thoroughly disgusted with the whole set-up. We finally got dressed and ready and were on our way. As we neared the actual front lines we could hear occasional small arms and machine gun fire. We could always hear artillery fire so that didn’t frighten us as much, but the machinegun and mortar fire had more than an unfriendly and treacherous ring to it it seemed. Arriving at one of our advance aid stations, we got out of the ambulance and just sat around for a while. Then an officer came out and told us to follow him. We walked down over a little hill and through an open field—one at a time and at five or ten yard intervals we walked up to the corner of a forest. Our job was to evacuate wounded men on stretchers down through the thick underbrush of that woods. It was hilly, and it was hot, and it was muddy. A guide came to lead us to the place where the wounded men lay. Up through the woods and down over the steep ravines and in a circle around the winding trail we crept. We finally reached our men and got them onto the litters and started the long trek back. If you’ve never been one of a team of four men who had to carry another man on a litter through a thick woods, you can’t have any idea how backbreaking it can be. In some places the trees were so thick that only two of at a time were able to carry him. Several times we had to hit the dirt when an artillery shell landed close by. After what seemed hours, for all I know it may have been—I really can’t remember how long it took, we arrived back at the starting point. We all sat down, said “To hell with the artillery”, and just rested. A little later we all ate some K ration.

Then they said that one of the litter squads—four of us—would have to stay all night. We matched. My squad lost. We stayed all night. I found myself a foxhole that was already dug. (This time it was a foxhole and not a slit trench—this was one of the kind that you sit doubled up in with your knees up under your chin, not the kind in which you lie down and stretch out flat.) Darkness came and there we were. I can think of very few times in my life when I felt so lonely and scared and miserable as I did that night. There was none of the beauty of flying through the white clouds and the blue sky like the glider ride offered. There was none of the heroic and conquering feeling like when the glider landed. This was just plain, honest-to-God, dirty, filthy, stinking war at its worst. I rummaged in my pocket and found a package of Lifesavers, and after pondering for a moment over the name of them—Lifesavers, I began chewing on them. I chewed them like some people chew their finger nails and for the same reason.

Then the artillery started—ours and theirs. Ever since I first heard artillery shells I decided on one definite theory: Unless I, myself, regardless of what anyone else said or thought—unless I was sure it was from the other side, I assumed that it was all our stuff going out. That night I couldn’t even convince myself that it was all going out. I’d lay there in the hole, bugs crawling down my neck and up my sleeves, and listen as they landed in patterns all around where I was. First you hear one hit pretty (Hell, there’s nothing pretty about it)—first one hits quite far away. Then another lands a little nearer, another a little nearer, and another nearer still. They seem to be coming along in a straight line right at you. Then they get real close and the dirt begins to crumble down from the side of your little trench. You hug the dirt and try to borough into the ground a little deeper; you try to pull your steel helmet down over your whole body; you begin to wonder if it will be better to get hit in the head or in the legs and whether to sit with your knees up and your head down or with your head up and your knees down and you just squirm there and try like all hell to get both down at the same time…and you pray…you have been praying all the time, but you pray a little harder; and you begin to think of all the good that you’ve done and of all the bad that you’ve done and you hope the good deeds far outnumber the bad ones. Then you suddenly realize that the shells are landing on the other side of you and are going on the other way. Then you realize that you’re pretty lucky and you hope that the fellow who is on up where they’re landing now has the same good fortune.

That is you do all of these things if you’re anything like me, and most of the fellows I’ve talked to have said that they feel the same way. There’s a big difference between being afraid and being a coward. The coward wouldn’t be there in the first place unless someone dragged him. Most all of the fellows I know haec been mighty afraid many times, but not one of them is a coward.

Belgium

14 January 1944

Dearest Mom – This is as far as I got with the letter about Holland…and it doesn’t look like I’ll get to a typewriter soon, so I’ll sent it on as is. Don’t take too seriously some of the things I’ve said here. Lots of other fellows over here go through far more hell than I do.

If I ever get a chance I’ll write another long letter about my trip to Paris…and then could follow another about Belgium. Let’s hope, though, that before I have time to write of all of these things that I’ll be home and can tell you all of the stories personally.

Love to all,

Lee

Ludwigslust, Germany

24 May 1945

Dearest Mother and all,

Everyone but me has been getting mail the last few days. No kidding, I haven’t had a letter from anyone for about a week now. I suppose that there are some letters for me on the way though.

Well, here is that long letter I’ve been promising you for so long. I’m sending a copy of the same to Aunt Ann and Aunt Peg and Mary.

Jean said in her last letter to send her letters to J S from how on. Is she coming home?

Tell Norma that I’m surely going to write her a letter real soon. I really liked her last letter a lot. See if you can get the twins on the ball and have them write to me.

I gotta go to a class now. I’ll write again soon.

Love, Lee

P.S. I suppose you’ll have to pay extra postage on this letter.

May 1945

Prime Minister Churchill and Marshall Stalin and President Truman have made their statements concerning the ending of the war in Europe. So now the time seems ripe for Cpl Patterson to make his. Those great men (or at least Churchill—I heard him) found it fitting to trace the war from beginning to the end, so I’ve decided to do it in the same way. One word of explanation: If at times this sounds a little egotistic, please forgive me. I learned long ago that the best way to have a letter pass the censor is to keep it personal—to mention yourself only and not your unit. So if at times some of the things I say I did sound as though they would require the help of a few other people, chances are that I did have the assistance of a great many other men.

I think maybe the last place I mentioned by name was Camp Reynolds, Pennsylvania. The place I went to from there was Camp Miles Standish, Massachusetts. It’s about 20 or 30 miles from Boston. I was there for about two weeks…once during that time I got into Boston on pass. On the 12th or 13th of May I boarded the good ship “John Erickson” and set sail for Europe. The trip itself was very quiet and uneventful. The weather was good almost all of the way and not once did I get seasick. For a day or two the ocean was a little rough, the wind was high and the air cold, but it wasn’t too uncomfortable. We sailed in a large convoy and must have zig-zagged all over the whole Atlantic for the trip took 14 days. The food was fair, except for an over-abundance of hard boiled eggs. Although there were probably some women in the convoy, I’m sure that there were none on our boat. Although there were countless rumors of submarines, I’m quite sure we were never pursued by any. At least we were never shot at. Some of the fellows on the boat got together a little show and it was put on in one of the large rooms several nights in a row…and a good show it was too. I went to church once or twice on board. There wasn’t much to do in the way of relaxation except to play cards on deck…and the breeze was usually too strong for that. The evenings were usually the most beautiful and peaceful part of the day. Of course we were under strict blackout every night. Smoking was prohibited on deck at night. Nearly all of the nights were black as pitch, and it was a little difficult to feel your way about the boat after the sun went down. I was lucky enough to be quartered on the top deck. The air was rather foul in the lower part of the ship, but where I was was rather pleasant. There was a loud speaker in the large room where I stayed. Every morning they woke us up with recorded music and the news. Since there were only two meals served each day it was almost necessary to get up for breakfast. Usually at noon we had soup and crackers or coffee and cookies. And I guess it’s about time for a new paragraph…

One fine afternoon land was sighted. This they told me was the coast of Ireland. Who made that decision I don’t know, but I had no reason to doubt that it was Ireland. Maybe someone happened to notice that the leaves of the trees were green, I don’t know.

We were still on board for three or four days after sighting land. But we finally docked at Liverpool, England. There was the usual throwing of cigarettes and candy and gum to the people on the dock. There was a great to-do when the first female was sighted. The next day we were packed bags and all off the boat and onto the solid earth of Britain. Our group marched through the winding streets of Liverpool to the railway station. There I saw the first results of the war in Europe. We passed several places that had been bombed during the early part of the war. One of the worst pieces of destruction was the post office. The whole building was demolished. All four sides were still standing, but the inside was only a pile of rubble. I imagined for a moment what commotion and inconvenience it would cause if the post office in Williamsport or Jamestown were suddenly destroyed.

At the railway station there were Red Cross girls and civilians passing out donuts and coffee. Then we boarded the train. The train was one of those European type with separate compartments rather than large coaches. There were six or seven fellows in each compartment, and the privacy was very good for horseplay purposes. The highest ranking soldier in it was a Pfc, so the order not to throw candy and gum to the kids was strictly disregarded. The trip across some of the English countryside was really impressive. It was early spring and the colors were really at their peak. Everything looked unusually clean and fresh. The land really looked great, but I suppose after two weeks on ship board any earth would have looked great.

The train trip lasted for a couple of hours, and we finally ended up at a place called Olton Park. Olton Park is a Replacement Depot. A Replacement Depot is referred to by most soldiers as a “Repple Deppel”. And a repple deppel is the source of the whole U.S. Army. Luckily I was only there for ten days, but I’ve listened time and again to the trials and tribulations of soldiers who have spent months in such places. In the first place arrangements are nearly always made for it to rain continuously during a fellows stay in such a place. And it’s always cold. And it’s damp. No one knows you and you don’t know anyone else…and furthermore no one including yourself gives a damn. The one bright spot at Olton Park was a beer tent which was set up just when I got there. I almost felt that it had been arranged for my particular benefit, because it had been completed the same day I arrived. That was my first introduction to English beer, an acquaintance that grew into a warm friendship. Another fellow and I went down with our canteen cups and had them filled for a shilling. As luck would have it the bartender had just tapped a new barrel, and it was spoiled. Well, we drank ours and wondered how many humans could thrive on such stuff. When we noticed several fellows pouring theirs out we began to suspect something was amiss. But it was too late…we had already gulped ours down. The next cut, out of a new barrel was much better. I had one pass from Olton Park into Chester, a town about 15 or 20 miles away. We had lots of fun there and had our first opportunity to meet the British civilian. The British civilian was very patient with us and we got along right well together.

After another physical examination I was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division. Even though now I think it is one of the best Divisions in the whole army, I hadn’t heard of it before. In fact I wasn’t at all clear on what the term Airborne meant. From Olton Park to Leicester was another pleasant train ride…this time in a day coach with a lot of other fellows. Our train arrived in Leicester station and we were picked up in trucks and taken to our new camp. This was on the 4th of June. We were really made to feel like somebody when we arrived there. Finally I was in an outfit. It was like being an orphan for six months and suddenly finding that you had parents to call your own. The camp is just on the outskirts of the city of Leicester in a beautiful spot called Braunstone Park. The camp was neat and clean, the food was excellent, and the fellows there were exceedingly friendly. There I learned the ways of the English civilian…and decided that people all over the world are similar in many ways. Two days after my arrival was D-Day, 6 June 1944. All of the fellows at the camp sat glued to the radio, and it began to dawn on me that I was part of a fighting unit. I had missed this particular battle—probably the bloodiest of the war, and certainly one of the most important—but I was ripe for the next one.

I think I’ve already told you most of what went on in Leicester. About the only thing I didn’t mention was the name of the place…and now I’ve told you that. I had a girlfriend there…everyone else had too. Many of the fellows married English girls and lots of them have children there now. I drank lots of mild and bitter and ate my goodly share of fish and chips. I spent all of my money as fast as I could get it, and when I did get a chance to take a furlough was broke, so I stayed in Leicester. It was there that I had my first airplane ride, and it was at one of those English airfields that I got a closeup look at a glider.

In July the fellows came back from France and we began getting acquainted and began training.

Then came Holland…then came my first glider ride. I’ve had two or three rides since, but landing on an airfield is infinitely different than landing in a field that’s being shelled by the enemy. About the only new thing I can add about Holland is a fact that you probably already know. The place was Nijmegen.

When our division was taken out of Holland we went back to France. Our camp was outside the town of Sissonne. It’s about 20 miles from Reims, the place where the unconditional surrender terms were finally arraigned. I’ve been on pass twice in Reims. It’s the home of some of France’s finest champagne, and in the center of the city stands the Reims cathedral, one of the oldest in Europe. One day I went inside the cathedral and stool spellbound at its beauty.

A platoon of the 50th Field Hospital was attached to our company for the trip into Holland, and when we came back to France they were detailed to run the hospital for the camp. I was detailed to work with them. There I really began my clerking career in the army. We were living a calm and peaceful life, when von Rundstead began his big push up in Belgium. Before that, however, I squeezed in a 48 glorious hour pass to Paris.

Paris… There never was a city like Paris. It was rainy and cold most of the time I was there, but I never saw such a bright and happy city in my life. Paris had suffered under the domination of the Germans for a couple of years, but there were no signs of any suffering that I could see. Paris refused to be depressed. In spite of hell, I think Paris would manage to be happy and naughty. There I had a room of my own in a beautiful little hotel. It was a room with a private bath, and it had a bed with sheets and pillows. But there was too much to be done in such a short time so I’m afraid I didn’t really take advantage of the luxury of that hotel, but it was nice to know that it was there anyway. I didn’t see the Follies Bergere, and I didn’t see the Eiffle Tower, or the Arc de Triumph, or Notre Dame Cathedral. But I did have the time of my life at some of the night clubs and at one or two of the shows. I did see the inside of the Paris Opera House, but couldn’t get tickets for one of the operas because they had all been sold out for days in advance. There I met an old friend of mine from basic training days in Camp Barkley. That same night I lost him in the crowd at the Club El Tamborine, and haven’t seen or heard from him since. We exchanged addresses like people always do, but I lost his and I suppose he lost mine…like people always do. I didn’t do any of the things there that I wanted to do. Paris is much too much to be taken in two days. People who have spent the greater part of their lives there have never really seen it all. You walk out onto the sidewalk and gaze at the crowd and try to decide which way to go. If by some magic you managed to go in all directions at once, you might be able to do the city in 48 hours. I just did my best.

Like I said before, then came the “bulge”. This time we left Sissonne, France by truck. Had any of really realized the danger of that day and night trip, we’d never have taken it so lightly. I guess Germans were infiltrating back of our lines by droves, but we—or at least I was—were unaware of it.

When our convoy arrived at its destination we began to set up tents for our Clearing Station. We just got them about set up when word came to take them down again and move. We moved several miles ahead—maybe back, I don’t know—and set up again. Some of the fellows dug foxholes and prepared for a stay. I was working during the day and had no foxhole when night came. Someone discovered a hay mow down the road, and thought it wasn’t as safe as a foxhole it was surely much more comfortable. The hay was warm and I had my bed roll and plenty of blankets. The nights really weren’t too bad at all—for me at least. It was at this place where I was homesick as the devil all of Christmas day. Our chaplain came over around noon and we sang a few hymns around a fire outside one of the tents. We watched a great many of our planes fly over that day, and were really thankful for the clear weather that permitted them to fly. I watched and almost cried when I saw a few of our own planes shot down. The machines burst into flame high above us and floated down to the ground. No one in any of them jumped out. There wasn’t time for that. It was Christ’s birthday, yet one man on the ground saw fit to shoot another out of the air and kill him. War is a damnable thing and it wouldn’t stop for anything.

I just asked a fellow here if we were still in the tents on New Years eve. He said no that we were at Chevron in that little house. He added, “I remember it was New Years eve and there I was with only one bottle of wine”. I said, “Hell, I didn’t even have that…if I’d known you had a bottle of wine I’d have been down to see you.”

That’s where we went when we moved out of the tents…to Chevron, Belgium. Chevron, as I figured it out, is something like Saratoga Springs in New York. It’s famous for a certain purifying water. Many people in peacetime went there on vacations and rest cures. Because of that there were some fine buildings there. I lived with some other fellows in a little house on the side of a hill. Our little hospital was at the top of the hill. It was a beautiful spot. We were lucky…we could live and work inside. Some of the Infantry men froze, while we were comfortable. I was thankful during that time that I was in the medica.

The only disconcerting thing about Chevron was the buzz-bombs. The vibration of a buzz-bomb is really something. Thank God I’ve never felt the concussion from one of them. We were down in a little valley and they sailed over our heads continuously. They usually came over at night, but once in a while they would send them over during daylight…especially on cloudy days. They travel so fast that you have to look way ahead of the sound to see the bomb itself. At night it is just a red ball of fire in the sky and during the day just a black spot. It was mighty eerie at night to lie in a sleeping bag on a litter and listen to the windows rattle and feel the house shake as they went over. The idea of them, I guess, is that when the motor stops they dive down straight and explode where they light. So our favorite song at the time was “Praise the Lord and Keep the Motor Running”. None of them ever hit where we were…I think they were aimed for Liege, Belgium several miles away. Once one conked out and hit some five miles away and the concussion where we were was terrific. As far as I know they never did any good for the war effort of the Germans, but their effect on moral was terrific.

The jet planes were something else. They are a propeller-less machine and look just like any other airplane but are much faster. They travel faster than sound too. All you hear is a horrifying swish through the air and they’re gone. One day one came over and dropped a bomb not so far from where we were and scared the daylights out of us all.

One of the fellows in my platoon went hunting one day and shot a fine deer. It happened to come at a time when we were eating mostly hash and stew, so the venison really was a welcome relief. We all ate deer meat and bread till most of us were a little ill for a while.

I’ve slept in some peculiar places since I’ve been over here, but one of the most unusual and yet comfortable was in a coal bin of a nice little house a few miles from Chevron. We set up an advanced aid station about ten or 15 miles towards the front. I was working nights at the time and it was really comfortable in that living room of that house with the potbellied stove going full blast and with the hot cocoa boiling continuously to be sipped on if there was nothing else to do. We weren’t too busy at the time, so we sat around doing quiz questions for entertainment. One of the fellows in our company has a cousin who sent him one of those pocket size Quiz Books every time she sent a package. One fellow would act as quiz master and the rest of us would answer the questions. I’m glad and proud to relate that I was in the upper bracket when it came to answering questions.

…but all the time there was artillery howling about outside. Some of the shells landed uncomfortably and dangerously close, but for some reason or other I wasn’t much afraid of them. That’s a funny thing about fear: Sometimes you’re not afraid when there is reason to be, and sometimes you get scared as hell when there’s nothing to be afraid of. For some reason or other I felt quite safe in that little house. When I got through working at seven in the morning I’d go down the cellar to my coal bin and crawl into my sleeping bag on the litter and really sleep. When there are shells flying about outside, a cellar is a pretty safe place.

I wasn’t too happy to leave Chevron. It had been a safe and comfortable place. There were four other fellows and myself in our little room. We had a stove for heat and extra cooking. (That was the place where the boxes of food that you sent were more than welcome.) One of the fellows who stayed with us was killed not so long after. He was a long, lanky kid. He was only about 19 or 20 years old and a quiet boy. One night he was trying to think of someone to write to and I gave him Colleen’s address. He wrote her a letter that very night. But we did have to move…

…and the next place awas Ligneuville (I hope you don’t try to find these places on the map, because I’m sure that the spelling of them is pretty atrocious). That move was made just after a snow storm. Never have I seen so many dead German soldiers as I saw on that trip. There were bodies on both sides of the road, some half covered with snow, some with little drifts of snow piled up against their still bodies. They had tried to remove all of the dead Americans, but I’m sure that among them there must have been some of our own men. The actual battle is real war at its worst, but the survey of the scene after the battle is really more pitiful. During the actual battle, there is no time for pity one man for another…there is barely time for self-pity. I’ve never been in an actual big battle itself, but I’ve been a witness of many scenes like this one close on the heels of the real thing, and it surely isn’t a pretty thing to see. It’s at times like this that all of the glory goes out of war.

We arrived at our new spot and found that we were in a hotel in the middle of town. Our aid station was to take up all of the space in the hotel, but again we were lucky and got a house to sleep in. There was a trail leading from the house to the hotel. There had been a terrific battle there a day or two before. Not a tree had been missed by bullets and shrapnel. Everything was torn to smithereens. I’d have hated to have been there a short time before. We hadn’t been there long till we had to move again. The men of our division had begun to attack the Seigfreid Line. We were pretty far back but there seemed to be no place for us to move. All of the buildings further up had been destroyed. Finally though they found a couple of houses standing several miles closer to the front. Our aid station this time was in a school house, and we slept on the floor of a former beer joint. That’s the first time I’ve had occasion to sleep all night on a barroom floor… I hope it’s the last time.

Then news came that our division was to be relieved for a rest. That was great news because we were all pretty tired and run down, but even as worn out as we were we had no reason to be half as tired as most of the infantry men we were supporting.

I can’t tell you the name of the place we went to for our rest. This time we found ourselves in a deserted insane asylum. It really was a nice place and we all had hoped to have a real reprieve from hard work for a while. We spent one night there and the order came to move again…this time into Germany.

I got my first good look at the Seigfreid Line. Surely people who saw that monstrosity being constructed must have suspected Germany of something. It curls like a giant snake over the hills between Germany and France and Belgium. There are huge triangular cone shaped concrete blocks embedded into the ground and here and there are concrete and steel “Bill boxes” with small openings for guns to protrude. A great many soldiers of all nations were killed trying to uproot those forts. They are painted green to match the foliage around them. If the constructor of that had used his ability for building buildings he’d have really had something.

This time we went to the town of Rotgen in Germany. This German town hadn’t been touched at all by our bombers or by artillery. Rotgen was a very lucky town. Our aid station was in a former German beer garden and we slept in a former German home. Nothing of much interest happened here. The weather grew somewhat warmer while we were there and there was the mud to contend with. I worked at night again and we weren’t at all busy for some time. We made lots of toasted cheese sandwiches over the potbellied stove and drank lots of coffee. It really wasn’t bad at all. (You know, when I speak of things being “not bad at all” I certainly don’t mean that they were at all pleasant. They are pleasant in comparison to some of the things that I have done or that I could be doing is more what I mean. Sleeping in a coal bin is much better then sleeping outside in a fox hole, and eating toasted cheese sandwiches and drinking coffee is infinitely better than drinking cold lemon juice and eating cold K rations.)

Only about one other thing happened at Rotgen that is worth bringing up. It was another move. Again we found ourselves too far back of the infantry men to be doing them much good, so we moved up closer. This time there was no house, hotel or barn to go in to. We moved right up near the bank of a river and began to set up our tents. We fully expected to be showered with some artillery that night so everyone began to dig a fox hole. We had all of the tents up and were all set to receive patients when the order came to tear them down and move back. We went back to the town of Rotgen and stayed all night and the next day began the long trip back to Sissonne, France.

There began the long process of “Sweating out” the crossing of the Rhine river. “Sweating out” a mission is one of the worst things a soldier can experience—especially an airborne soldier. The jumpers were sweating out the parachute jump and we were sweating out the glider ride. You try to live in the present and to take advantage of the fairly decent living conditions that a rear area affords, but somehow or other your thoughts drift to the future and you begin to imagine all kinds of catastrophes that might happen. I myself don’t take the sweating out period quite so seriously as a lot of the other fellows do, but it’s no pleasant experience no matter how calm you are able to be.

In Sissonne we lived in tents, but luckily the weather was pretty nice so it wasn’t too uncomfortable. We had the opportunity to see some pretty good shows while we were there and I began to do my PRO work and that kept me pretty busy. Maybe that was one reason the thought of an airborne mission across the Rhine didn’t bother me so much. I wrote up several stories on several of the fellows in the company for their hometown papers. I like the job a lot (I still do some of it yet). Some of the clippings have found their way back to the company and I’ve been glad to see that the papers saw fit to publish them just the way I wrote them without any changes.

It was a happy day for our group when that bridge was captured at Remagen and our troops began pouring over the Rhine on foot. A few weeks later it was a much happier day when the actual crossing was made without an airborne mission on the part of the 82nd Airborne Division. Some parachutists and glider men were used in the northern sector around Holland, but this was a British Division and another American Outfit. We were pretty sure then that all airborne operation were over…in Europe at least.

I’m glad that we got in again for the final kill. To see the German war machine break up as it did is a sight I’ll never forget. First we went to Cologne.

Cologne, Germany is really a ruined city. Never have I seen such destruction on such a large scale. There is a city about the size of Pittsburg flattened out completely. They say that the city has been about 85% destroyed. I was unable to see the 15% that wasn’t supposed to be destroyed. I guess they must have been referring to the outskirts of the city, for there was certainly nothing left of the heart of the place. I had occasion to go into town several times and it really was something to see. And right there in the middle of all of that rubble is the beautiful Cologne cathedral unhurt. That surely is a tribute to the Allied Air Force. Within a block of the cathedral is a railroad station that is smashed completely, and on either side of the cathedral is a bridge that has been blown out…yet the cathedral still stands in one piece. One day I walked with one of the officers in our company halfway across the one bridge. So I was one of the first in my company to get partway across the Rhine. Do you remember those puzzles that we used to do in some of the papers where you took a pencil and traced a line from the outside to a point inside the picture and you weren’t allowed to cross any lines doing it. That’s the way it was trying to get through the streets of Cologne. You’d drive for a while towards a point and suddenly the street was completely barred with rubble. You just had to turn around and try another course. It was just as hard to get out again.

This time we were in a big hospital—“krankenhaus” in German. That’s one of the few German words I know. It had been a beautiful place. It still was a beautiful building for that matter except that nearly all of the windows had been blown out. There were lovely big bath rooms and electric lights. We had quite good food and even a mess hall to eat in—with real tables and chairs.

Here began the policy of non-fraternization that General Eisenhower has ruled shall be strictly enforced. We are not allowed to talk to any Germans—man, woman or child. It’s pretty hard to be around people all of the time and not be friendly with at least some of them. You see a pretty girl walking down the street and the natural thing seems to be to get acquainted with her and to get to know her better. You see an old man or an old woman and it seems only natural to at least greet them in a pleasant manner. Or you see some little kids playing and you feel that you must dig down into your pockets and bring out some candy or gum for them. I suppose the problem of the kids is the hardest for most of us. GI’s just naturally like kids of all nations, and kids seem naturally to like GI’s. It’s pretty hard to ignore people as it is on us, and it is in the form of punishment for them not to be able to associate with us…and small punishment it is at that. (After I got further into Germany and saw some of the concentration camps it wasn’t nearly as hard to ignore them all completely.)

Our whole company was ordered to move again after the Cologne pocket was cleared. One officer and nine or ten men and myself were to stay for a few more days at the “krankenhaus”. We were there for five or six days. We all moved into one wing of the place and lived like kings for the time we were there. We had sheets on our bed and even had maids to make up the beds and clean the room. We had a couple of wine parties on a couple of nights and everyone had a real gay old time. But finally we too had to leave.

We joined the company at a place not so far from Hamburg, Germany and the battle went on. The Germans at this time were retreating at a terrific speed and it was all we could do to keep up with them. We spent a night in the mayor’s house near a little town and moved on again.

Then we crossed the Elbe River and began to see the disintegration of the whole Germany armies. The first night across the river we stayed in a barn just on the other side. It was that night that we heard of the death of Herr Hitler. From then on there wasn’t much to it. The Germans were surrendering in droves. I even captured a few myself. Well, I didn’t actually capture them…you don’t capture a helpless little kitten that is unable to walk. Capturing a German at that time was about the same thing. We moved into a German Labor Battalion Camp near Lubtheen (Spelling is uncertain again). This was a regular army camp like any you might find in the U.S. The afternoon we got there we had hardly had time to settle—we were waiting for the Engineers to come and go through the camp to test it for booby traps and mines, when a group of Jerries came marching down the road. They were unarmed but there was no guard with them. Some of our guards went running out to see just what in hell was the idea. The Krauts said that they had been told to march down alone to the prison cage. There were too many prisoners for the guards to handle. One soldier came down the road alone and one of the fellows went out and stopped him. At the time I was trying to get some sort of office together so we could get out our reports that night. I looked up and there stood this German soldier in the doorway. He wished to surrender. The fellow outside just stood there laughing at me as I stood there wondering what to do. That’s the story of how I captured the German.

The next day is one I’ll never forget. From early day light till late at night they moved past our camp. It seemed that this must have been the whole German army there at our front door. They were in cars and trucks. They were on horse drawn wagons and bicycles. Many of them walked. It was an endless caravan of beaten soldiers. It was the end of a once proud army. It was a little sad. You couldn’t help feel a little pang of sorrow for some of them…at least I couldn’t. (I still hadn’t seen the concentration camp.) Once in a while a French or Russian or Polish refugee would run out onto the road and take away a car or a bicycle for himself. There was nothing the Germans could do but get out and let the other fellow have it. It was no more than fair either, because it’s a long way from Germany to France and Russia and Poland. Why should these men walk while the beaten Germans rode? No one stopped them.

That just about brings us up to date. The next move was to the place where I am now. The place is Ludwigslust, Germany. It’s between Hamburg and Berlin on the map. It’s just a small place so you might not be able to find it. Oh, along in there I should have mentioned that the war over here ended. You see the events leading up to V-E Day were so much more exciting over here than the real surrender day was itself that it made very little impression on anyone. We were told about 24 hours before it was made public that the war had ended. I thought that was a nice gesture on the part of the powers that be—to let us in on the thing before the general public knew about it.

Things are pretty dull now. There isn’t a heck of a lot to do. Of course the captured horses and bicycles and motorcycles are taking their toll on our troops. We have some patients every day from some accident or other. Once in a while one soldier shoots another accidentally. But at least the big fight is over and our job here is done. The fighting part of the job is done I should say. There are still all of these displaced and starved and maltreated people to be got home to their own lands. There’s a new government to be set up in Germany itself. And there are a hundred and one other little jobs to be done; but the fighting is done.

I wish I knew what the next move is to be. I wish I knew if I would get home at any time soon. But I don’t know. Time alone will tell.

Cpl Lee M. Patterson,

Ludwigslust, Germany

STL Archive Records

Died July 24, 1967