Charles Sartain

ASN:O-466381

Charles Lenton Sartain, Jr. was born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana on September 19, 1920. His father was a railroad conductor, and his mother had a teachers certificate although she did not teach after she married. Charles attended a public elementary school and a Catholic High School.

Captain Charles Sartain

Sartain attended LSU in the summer of 1938 and finished his Pre-Law studies in June 1942.

In those days, Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) was compulsory for the first two years. Sartain then enrolled in advance military training for his last two years at LSU, graduating in 1942.

He was commissioned a Second Lieutenant and assigned active duty to the Army’s artillery school in Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

“I was in a pack outfit (a military unit that used pack and saddle animals such as mules, to operate in mountainous terrain) at Fort Sill for about six weeks,” Sartain later explained. “One of the reasons I joined the paratroopers was to get away from those damn mules. I knew the pack outfit was headed for the pacific and New Guinea. And I wanted no part of it.”

And so Lieutenant Sartain volunteered for the 82nd Airborne Division after finishing his basic course of training.

Lieutenant Marvin Ragland was the only other 319th officer he remembered in his class. He was then transferred to North Carolina’s Fort Bragg to join the 319th Glider Field Artillery.

Sartain’s service with the 319th glider men

During the first months of training, large numbers of draftees and newly enlisted personnel were being introduced to U.S. Army life by a small cadre of experienced regular army officers and Non-Commissioned Officers. These soldiers clung to long-held traditions. One of these was the practice of supplying officers and senior NCOs with coffee and biscuits during breaks in the day’s training schedule. Enlisted men were not allowed this refreshment.

Second Lieutenant Sartain thought this was unfair and worthy of addressing. worthy of addressing. He later reminisced that “The average G.I. would see his sergeant leave him on the training field to go to the mess hall and get a snack of biscuits and coffee…while the others would have to wait until their superiors returned to continue their training. It just wasn’t right. So I talked to the battery commander and asked him to issue an order. Either everybody could come by for biscuits and coffee or nobody could. So they put an end to the biscuit and coffee breaks.”

The request backfired. Perhaps Sartain had been naive. It caused irritation among those whose special privilege was suspended. But Sartain’s effort didn’t go unnoticed by the enlisted men. Sartain also had the habit of always going to the end of the chow-line and never pulling rank and cutting in line. The privates and corporals saw this, and knew they had a friend in the Lieutenant from Louisiana. In the end, the coffee and biscuits affair was a lesson for Sartain about the consequences of challenging entrenched traditions without preparation. For the young Lieutenant, it was a lesson well learned.

Sartain’s devotion to the men under his command in A-Battery continued to grow. When orders came for him to attend “jump school” at Fort Benning, Georgia, Sartain was also told that when he finished his training, he would most likely not return to the 319th Glider Field Artillery. Instead, he would be reassigned to a parachute artillery battalion.

When he learned this, Sartain declined the opportunity. Looking back he said, “Remaining with A-Battery was the best decision I ever made.”

North Africa

A-Battery and the rest of the 319th arrived in Casablanca, Morocco, on May 10th, 1943. More on-the-ground training followed.

That summer saw a reorganization of the battalion from two 6-gun batteries to 4-gun batteries. The exact reason for the new configuration wasn’t known, but some evidence indicates it had to do with upgrading the battalion’s weaponry with shorter-barreled 105mm howitzers, a more robust piece of field artillery than the 75mm “pack” howitzers with which they’d trained.

B-Battery “pup tent” - Kairouan, Tunisia - 1943

The creation of this third C-Battery gave the A and B Battery commanders a chance to weed out the “oddballs,” the most difficult men in their command, and dump them in the new battery.

C-Battery was placed under the command of Captain John R. Manning, with Charles Sartain as his executive officer. At the time taking over a new Battery was regarded as a big challenge. But Manning and Sartain saw it as an opportunity to demonstrate their shared theories of leadership.

Decades later, Sartain expanded on his theory. “We started C-Battery knowing we had some oddballs. But we had some solid guys too. And we didn’t treat anyone as an oddball. We never said anything to them. We just treated the men with respect, gave them responsibilities, and they just came through for us. The feeling throughout C-battery was ‘by golly, we’re going to show them.’ And we did.”

Sartain went on to reflect, and quite proudly, that “We had a very cohesive unit. We were the best battery, always on mission first, ahead of the other two batteries. We beat A and B Batteries consistently. That’s why I believe Colonel Todd took a liking to Captain Manning and me. “A little ole Second Lieutenant - me - was made the battery exec. Now that’s not normal or usual. I guess he made me battery exec so he could promote me to First Lieutenant.” Throughout the battalion, Sartain’s reputation among the men was apparent.

PFC Milton Goldfarb

Somehow, he treated them all with respect and had their best interest at heart. And they knew it. Sartains’s background in pre-law studies became known throughout the battalion. And it led him to play the role of defense attorney at the special court-martial of a B-Battery soldier named Milton Goldfarb. Goldfarb (see inset) was accused of falling asleep while on sentry duty. So, a special court-martial was convened. The event was a flashpoint for the growing resentment among the officers and enlisted men of the 319th toward their commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Bertsch. Sartain said that Bertsch made little effort to conceal his contempt for anyone who did not share his West Point pedigree.

“The first court-martial I conducted was how I got my guardhouse reputation,” Sartain remembered. “A fellow by the name of Goldfarb with B-Battery was on guard duty. He was accused of sleeping on duty. Colonel Bertsch and his driver saw him undereneath a cactus plant. The Colonel wanted to throw the book at him.”

“Major Todd asked me to defend Goldfarb. It was what we called a special court-martial. Three officers from the battalion presided. Goldfarb testified that he wasn’t asleep, that he’d lost the head of his flashlight. It had fallen under a bush, and he was trying to find it when the Colonel’s driver confronted him. The Colonel’s driver couldn’t swear if Goldfarb was asleep or was really searching for the top portion of his flashlight. So, to make a long story short, the court-martial judges found Goldfarb not guilty. The next day. Colonel Bertsch called me into his tent and accused me of using my meager knowledge of the law to disrupt the discipline of his command. No wonder nobody liked Bertsch.”

In July of 1943, the 319th Glider Field Artillery was called on to participate in the invasion of Sicily, known as Operation Husky. It was to be the first large-scale airborne operation and one which called for close co-operation with our naval forces. Sadly, when tragic errors resulted in airborne personnel being killed by friendly fire, the role of the 319th was canceled at the last moment.

Naples-Foggia, Italy

A-Battery’s baptism of fire came in September 1943 as part of Operation Avalanche, the invasion of the Italian mainland. Ironically, for the glider artillerymen, it was an amphibious operation.

“Let me tell you about Italy,” Sartain later said. “Maiori was a little village on the Amalfi coast surrounded by horseshoe-shaped mountains. The only way out of the village was via a narrow lane through the Chiunzi pass, which we called the ‘88 Pass.’ Our battery was set up on the back (ocean) side of a mountain, in a big vineyard. We rolled the guns below the road into position. After we cut the wires holding the grapes up, we fired our howitzers. Then, we’d pull the wired back to camouflage the battery.”

The terrain was so mountainous that the 319th gunners couldn’t elevate their howitzers enough to hit our targets. We solved this problem by digging deep trenches to achieve an angle of fire that was nearly vertical. Sartain explained, “we were so close to the back of the mountain that we had to use those guns like a mortar. We would take out a couple of the powder bags and launch that damn shell over the mountain and let that shell drop right at the bottom of the other side of the mountain.”

Our mission was to interrupt the movement of German supplies and reinforcements from Naples in the north, down to the allied beachhead at Salerno. “We had the battery in position and our forward observers would go up the mountain and monitor the gunfire. It was a real sport to register the different concentration points. You’d have to figure out how long it would take for that shell to reach its target. Then, when you saw an enemy convoy coming, you timed it. You’d shout, Fire! And the gunners would fire. Then, you’d watch and see if the shell and the convoy arrived at the same time. You watch the convoy, and when the enemy began to scatter, you knew they could hear the howitzer shell coming at them.”

C-Battery - enters Naples, Italy - October 1,1943

Once they broke out of Salerno, the 319th entered the City of Naples. This was on October 1, 1943. It is reported that elements of C-Battery were among the first to enter Naples. They then saw further combat action along the Volturno River, about 40 miles north of Naples.

By the time Sartain and his men returned to the city as occupation forces, the Second Lieutenant had been promoted to First Lieutenant Sartain.

Ireland and England

When 1943 ended, Charles Sartain’s battalion was quartered in Quonset huts in Northern Ireland. Daylight was in short supply and allowed for only limited training, mostly marches to keep the men in condition. Gunnery practice was difficult because of the restrictions placed on military operations by the local authorities. “You couldn’t even dig a hole in Ireland,” Sartain later commented.

February 1944 saw the 319th was moved to a 17th Century manor house located outside the town of Lubenham, a tiny hamlet near Market Harborough, England.

At the end of February, the arrangement of three fire batteries was discontinued. The battalion returned to its previous configuration, two firing batteries and one Headquarter battery. The men from C-Battery were returned to their former batteries, but the duo of Captain Manning and Lt. Sartain as his executive officer, had proven so effective they were placed in charge of A-Battery.

Papillon Hall - Market Harborough, England - August ‘44 - (L-R) Lt. John Gutshall, Capt. Charles Sartain, Lt. Marvin Ragland

Early in March 1944, Sartain was again asked to serve as defense counsel in a court martial. He’d already defended Milton Goldfarb in North Africa, and in Naples, Kenneth Smith of his own C-Battery, for procuring a sack of flour by “unconventional means.” There were others, but this time the defendant was a troublesome officer of A-Battery.

Lt. Harry Vereen distinguished himself in combat, but he had a reputation. As Sartain put it, “he had an alcohol problem, and he had a woman problem.” This officer had already faced a court-martial in Naples the previous November, now, in England, he was at it again. According to the latest charges, Vereen was discovered staggering around drunk in a downtown Leicester parking lot. Sartain defended him and in the end his client was fined $100 and released. “I don’t know what that court was thinking,” remembered Sartain, “It was a real shocker. Everyone was surprised except Vereen, he was disappointed, he really thought he was going to get off. Afterwards Todd and Wilcoxson really had the red ass over the verdict. Todd wasn’t mad at me though. He was a lawyer. He knew my job was to defend him. A defense lawyer gets his client off and Todd understood that.” Looking back on the trial years later, Sartain observed, “Soon after Vereen just disappeared. Nobody said anything. Nobody said, Major, what happened to Vereen?…he was just gone and we never heard from him again.”

Normandy - Operation Neptune

Crashed CG-4A glider - Normandy

Photo courtesy of the Pongracic Family

The 319th glided into Normandy late in the evening of June 6, 1944. Casualties were high, as was anticipated. Some were killed or injured by ground and anti-aircraft fire before their gliders were released. Many more were added to that grim list on landing. Few of the gliders came to a stop intact. Nearly all crashed into trees or hedgerows or became fouled in the German’s anti-glider defenses. These defenses were typically telegraph or railroad poles, planted vertically, then outfitted with explosives and interlaced with wire entanglements. In all, the 319th suffered nearly 30% of its personnel killed or wounded.

“We were in a Horsa glider,” Sartain remembered in a 2005 interview. “The pilot over ran an open space and ended up in a lane at the far end of the field. The trees tore off the wings, but we remained upright and finally came to a stop. It was near a small farm home with a large barn, all enclosed by a stone fence. The home was occupied by at least a platoon of Germans and there was a lot of enemy traffic to and from the farm.

Sartain and his small party approached to within a few dozen yards of the perimeter wall. Expecting to be discovered or all hell to break loose at any moment, he had drawn his Italian Beretta automatic because “that damn .45 automatic they gave us was useless, unless you were close to whoever you were shooting at.” After a while they heard someone calling, “Americans! Americans!” it was a French farmer. “How he knew we were out there I’ll never know,” Sartain recalled. “But he told us the Germans were all gone.” Thankfully, Sartain could still remember a little of the French he’d grown up around spending summers with his mother’s family in rural Louisiana.

Through a conversation in broken French, Sartain learned that they were about 3 miles from the landing zone and the assembly area, near the small village of Etienville.

“Most of the night we worked our way from hedgerow to hedgerow. Along the way we picked up about six more 319th members. We then decided to wait until daylight always staying hidden. When daylight came, we moved out, one hedgerow at a time. There were German motorcycles coming and going. We could tell that they were very confused. We finally got to our assembly area about noon.” That’s when Col. Todd called me aside and said, ‘Charlie, (Captain) Manning has been badly injured. He’s already been evacuated. You need to take over the battery.” Thus, began Sartain’s tenure as Battery Commander, a position with which he became most closely associated for the rest of his life.

“Captain Charlie” as he came to be known among the enlisted men, also spent enough time calling in artillery fire from a piper-cub aircraft to earn the Army Air Medal. It was hazardous duty, not only because of enemy fire, but more so because the L-4 Piper-Cubs were forced to take off and land among small fields surrounded by tall hedgerows.”

“I made about 70 aerial observations,” said Sartain, “Then I got awarded the Air medal with a cluster, but Col. Todd put an end to that. He told me Charlie, you like being head of A-Battery? Well, you’re going to either be an aerial observer or you can be a Battery commander. If you want to stay as Battery commander, then keep your ass out of that plane.”

Sartain emerged from the Normandy Campaign as Captain and Battery commander, with a growing reputation among not only the men in his command, but among the officers leading the infantry units which his battery supported. Particularly among these was the 3rd Battalion of the 508th Parachute Infantry, led by Lt. Col. Louis G. Mendez.

Holland - Operation Market Garden

On September 18, 1944, the 319th as part of the 82d Airborne division, participated in the invasion of Holland. The objectives were ambitious and had the course of events gone differently, would certainly have had a profound effect on the course of the war. As it turned out the fighting in Holland deteriorated into a long, drawn-out slugging match, a “dogfight” as Sartain later put it.

For the two months the battalion spent in Holland its position, though shifted several times, remained in the vicinity of Nijmegen. All the time in support of the 508th Parachute and 325th Glider Infantry regiments.

Barkston Heath Airdome - (L-R) Lt. John Gutshall, Lt. Laurence Cook, Lt. Joseph Mullen, Lt Marvin Fellman, Lt. Marvin Ragland, Capt. Charles Sartain - “the morning before the glide into Holland”

One episode in particular exemplifies Sartain’s qualities of command and character. Sartain later described what happened on September 25th: “It was my policy to check on the forward observers regularly. One afternoon when things were kind of quiet, Johnny Manning and I went up to this hill to check on Lt. Fellman – he was our forward observer there. The platoon commander was not there nor was the platoon sergeant. Well, just as we got there the Germans hit us with everything, tanks, flame throwers and everything else.”

Army records reveal that Lt. Marvin Fellman, one of A-Battery’s forward observers, had been placed with a platoon from “E” Company of the 325th Glider Infantry, on an elongated promontory known as “finger ridge.” The position commanded a choke-point on the road running along the north bank of the Maas river and thus could block any German efforts to reach points westward. Potentially cutting the only real highway between the allied lines and the beleaguered British Paratroopers at Arnhem.

“The thing is,” continued Sartain, “These kids didn’t know what to do. They were not seasoned airborne troopers… you could just tell. They were frightened. You know, so Manning took over the radio and I took over the infantry, reorganized them, kicked a few kids in the butt and then we were ready. But they were not seasoned airborne troopers you could just tell.”

Manning and Sartain, who had already shown their ability to lead and inspire, reacted in just the way the situation called for. “ (Captain) Manning took over Fellman’s radio. Fellman was the forward observer. He was over in the foxhole with Manning, and I’m delighted because Manning was a lot savvier about artillery fire. Fellman was just, you know, brand new. I’ve said if it hadn’t been for Manning on that artillery we never would have survived. Manning had that whole battlefield zeroed in on concentration points. All he had to do was call for concentration point 11, or concentration point 7, or whatever, and man the battery came in.”

James Todd, Charles Sartain, Andrew Hawkins, Unknown (L-R) - Dec. 1944

When asked how an officer turns a disorganized collection of soldiers on the verge of retreat, into a resolute band determined to hold their ground, Sartain explained his method. “You keep going among them. You keep going among them and give them a little spirit and then they start responding. A couple of them I had to kick in the butt. One guy couldn’t get his gun going. He kept telling me, it’s jammed, it’s jammed! So I said, well you know how to break it down and clean it, clean the son of a bitch! Clean it, clean it! After a while I passed him again, he’d broken it down and cleaned it. He was firing and he was so proud of himself. You know what I mean?”

At one point the Germans attacked with a flame-thrower. The weapon was notorious for provoking terror against those upon whom it was directed. “Well,” said Sartain of it, “when the flame thrower hit us, we had to bring one gun in (range) about forty yards from us. If it’d gotten any closer, he could have hit us, but that flame-thrower was only about forty yards away. We were just out of his range. Well, it was interesting.”

“We fought them throughout the night. I organized the troops, but they kept attacking us all afternoon and all night. We fired phosphorous shells to light things up once it was dark, you know, and I was credited with organizing the infantry and bringing in the artillery. That’s when I got the Silver Star.”

“The thing that amazed me was that we got absolutely no reinforcement from our headquarters. It was like those kids were stuck out there and nobody even knew they were there. That’s why I said they had to be new recruits from the 325th, because I couldn’t see anybody from the 508 being involved in a situation like this.”

Sartain and Manning both received the Silver Star for their actions that day. His citation read: “For gallantry in action, 25th September, 1944, near Holland. The battalion assistant S-3 on routine inspection tour of forward artillery Ops in the area observed three squads of German infantry moving in and taking positions to cut off a friendly infantry platoon holding the position. He immediately made his way to the infantry position through heavy small arms fire and found the position under attack by a superior number of the enemy, supported by tanks and flamethrowers. The battalion S-3 assumed command, while Captain Sartain, with the utmost coolness and courage, went about reorganizing the position, passing among the men time after time, giving encouragement and instruction to each individual soldier. His courage and devotion to duty, in utter disregard of his personal safety, was a great factor in halting the attack and holding the position until the arrival of reinforcements and resupply of ammunition. His courage, coolness, and conduct under fire was an example and inspiration to all the men in the position and exemplified the best traditions of the service.”

Capt. John Manning (left) and Capt. Charles Sartain awarded the Silver Star for bravery, courage, and disregard for personal safety while under attack by a superior number of enemy - Sept 25, 1944 (see photos below)

“The Bulge”

The Ardennes, or “Battle of the Bulge,” as it is popularly known may well have been the most trying of the 319th’s campaigns. In reality it was two battles fought simultaneously: one against the German army, in this case often fanatical, aggressive SS formations, and the other against unrelenting winter weather. While the former posed the more obvious and immediately deadly foe, the toll of fighting in winter was, in fact, greater than battle casualties.

American troops serving in northwestern Europe were generally not supplied with specialized winter combat clothing. Ironically, most of the clothing developed for severe weather, such as alpaca pile caps designed to protect the ears and neck, were distributed to those divisions fighting on the mountainous Italian front.

With temperatures hovering between zero and freezing, problems with inadequate winter gear made themselves known almost immediately. American combat boots, for example, were notorious for not allowing sufficient room for extra socks or to flex the feet. Though the men in Sartain’s battery tried stuffing their jump-boots with straw and chaff the measure was largely ineffective. Frostbite claimed an alarming number of men.

PFC William Bonnamy (loading 75mm shell) wearing an improvised “hooded scarf” made from blankets

Exposure of the ears, neck, and face could, however, be addressed but only in a way which skirted Army regulations. So in late December 1944, once the battalion was settled into a secure defensive position near Froidville, Belgium, Sartain did what he could to see after the men’s comfort. “I saw a sign in one of the houses where the lady took in sewing,” he explained. “So I gathered about 15 blankets from Harold Jinders in supply and the lady made us enough scarves and hoods for the battery. She cut it and sewed it on the top and put it on the edge and it came down just below the back of your neck. (see inset) It was worn under their wool knit cap and helmet, so the neck was kept warm. But as for General Gavin, he was a stickler for regulations and if he had ever seen one of these, he’d have raised hell. I kind of worried about it. We’d have to hide them if Gavin was going to come because he’d have considered us out of uniform and accuse us of desecrating army equipment.”

CPL Ted Simpson

Perhaps one incident from the Bulge represents Sartain’s character as well as any account of his leadership in the heat of combat could. Ted Simpson (see inset) was one of the replacements sent to the outfit just prior to Normandy. When asked about Sartain over sixty years after the war Simpson vividly recalled one episode during the Bulge. “We were on a hillside one night with our bedrolls. It was cold, it was miserable. We had been in contact a good bit with the enemy and it was just one of those nights when you didn’t know what was coming tomorrow. Sartain came up and sat down and talked to me a few minutes. How you getting along, where you from, that sort of thing. Very one on one. It was one of those warm and friendly conversations. I didn’t really know the guy very well so everything he said was illuminating to me about him. My thought at the time was how can he spend so much time with me? I’m just one of many guys around there. Yet by God he came up and set down and we had a couple of minutes together. It was just really wonderful. It made me feel good and then he went off. I expect he was doing the same thing with a variety of soldiers. Quite a guy.”

The Bulge campaign dragged on through January and into February of 1945. During these last months of the war Sartain seemed deeply disturbed by what he witnessed: social demoralization, destruction of property on a massive scale, and the very worst of human nature given free reign.

In April 1945, he found himself serving as defense counsel for a 319th man charged with sexual assault against a German woman in a Cologne (Germany) apartment. At the end of the sordid affair his client was found guilty and sentenced to five years at hard labor. It was one of the few cases Sartain lost during his career as a, “jailhouse lawyer.”

Unknown, Jesse Johnson, Charles Sartain, John Gutshall (L-R) Germany - 1945

Thinking back on the sentence, he remarked, “Five years. Well, it could have been a lot worse. Molestation of civilians, General Gavin would have none of it. None of it. Anybody that would mess with a civilian was court martialed. As battery commanders we had to stay on top of all that conduct, and we did. But generally, I think the men were pretty well disciplined. This did not happen often, but I was assigned to defend some knuckleheads of that type.”

Sartain went quiet, trying to find an adequate closing to an unfortunate series of past events. He reconsidered then spoke. “You know, there were a lot of cases they had to dismiss because civilians would not testify. They were scared and of course the men knew that. A civilian woman was not going to testify against a soldier. They were scared and they didn’t want to cross that bridge.”

By May 1945, Sartain had to deal more and more frequently with “knuckleheads.” Looting, for example, not just American but British and Canadian troops as well. Once the battalion crossed the Elbe River it became clear from the thousands of refugees they encountered, the Soviet forces the 319th would soon meet, were conducting outrages against civilians on a scale not seen for many generations. As sobering as these events were it was the discovery of the Wobbelin concentration camp a few kilometers outside of the city of Ludwigslust, Germany, which made the sharpest impression.

“When I went to see it many of the victims were still there,” he said. “It was horrible. I didn’t get to go inside but I walked along the wire. All these people were lined up; they were going crazy, hollering, and putting their hands through the wire to touch you. They wanted to hold your hand and all of that business. I was pretty well shook-up to see it.”

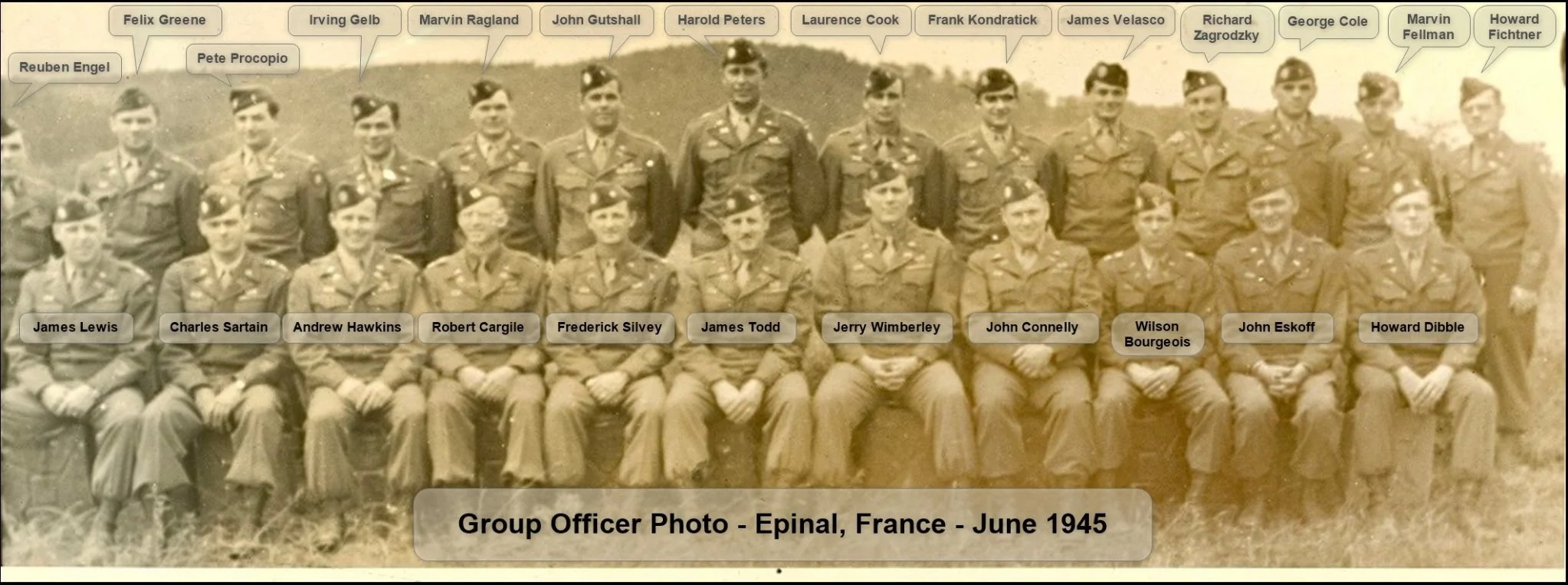

Going home

In June 1945, all the high-point men (the point system the U.S. Army used at the end of the war to determine when soldiers were eligible for discharge) Sartain included, were transferred from the 82nd to the 681st Glider Field Artillery of the 17th Airborne division. Low point men from the battalion were, likewise, transferred to the 319th. It was a giant reshuffle which allowed the 82nd to remain active at full strength, allowing an administrative avenue through which its most veteran personnel were sent home and discharged.

Sartain himself became “athletic officer” of the 319th, then the 681st. For him it was a let-down. He regarded the position as a joke, for it was clearly a way to keep supernumeraries like him on the rolls of a battalion staff which already had too many officers.

Frank Kondratick (standing L-R), Richard Johnson, Howard Fichtner, Robert Cargile,

Marvin Ragland, James Todd, Jerry Wimberley.

Reuben Engel (kneeling L-R), Joseph Mullen, Charles Sartain,

Felix Greene, Maxwell Torgersen, James Miller.

Camp Suippes, France - 1944

Interview with Charles Sartain - 2005

Initially, Sartain felt short-changed, convinced his service had been rewarded with a trivial position on the battalion staff. As days passed, however, he came to comprehend the decision. “When Colonel Todd gave the Battery to LT Ragland, I didn’t know how to handle it,” Sartain admitted later. “I can appreciate it now and I really feel like Todd was trying to give me a rest, but for sentimental reasons and everything else at the time I really wanted to come home with the battery. Instead, I came home as Athletic Director. When I look back over it now, I can see it was the one way Todd could get Ragland promoted. And Ragland was a good CO, he richly deserved it, he really did.”

While Sartain had his own personal misgivings about leaving as commander of A-Battery there was also a widespread anger among the transferred men on learning that they were to remove their 82nd division patches and replace them with the eagle’s talon (patch) of the 17th airborne. Many of these men had served for three or more years in the “All American” division. Its record was unequaled. To learn that they were to remove their unique insignia seemed a slap in the face for their sacrifice.

Eventually a compromise was reached. Those who’d seen combat service with the 82nd were allowed to wear their All-American patch on their right shoulder, but the “eagles talon” of the 17th had to be sewn to the left shoulder.

Today it is an accepted practice throughout the army for soldiers to wear the patch of the unit with which they first see combat on their right shoulder. “So, we switched the 82nd from the left to the right and put the shit-hook on the other side,” commented Sartain. “We called that the shit hook, that’s right. I hated having to wear that. I really wanted to take it off.”

Before starting home in the final parade of the 17th before Major General Miley, its commanding officer, the men of the old 319th acknowledged their commander by saluting with their fingers turned inward like a claw. Sartain was hugely amused by the whole stunt. “Yeah man, we gave them the claw,” he recalled, “But Todd put an end to that business in a hurry. He told us cut all that crap out! But we didn’t give a damn. We were ready to go home.”

Sartain was among the first wave to be brought home and discharged in September 1945. Everyone’s attention was fixed on getting home as quickly as possible. There were jobs to return to, wives, and sometimes children as well. There were girlfriends and fiances whom many of the single men were eager to marry and start their lives with.

When interviewed about his wartime experiences in 2005, Sartain sat quietly in his chair and packed his corncob pipe then lit it and began to reminisce. “A-Battery of the 319th was a very, very important part of my early life, it really was, and now having aged, when I talk about things, I get very sentimental. It’s very difficult for me to keep my composure when I talk about things I dearly love. And A-Battery was really something else. I didn’t realize it was as special as it was until the damn thing was over with, but looking back over the years, I understand that now.”

In the years which followed Captain Sartain’s significance to those who served under him was apparent. His daughters related more than one phone call or letter from a veteran down on his luck asking “Captain Charlie” what he should do. Typical would be the A-Battery veteran who, on being interviewed about his service would ask, “What about Sartain? Have you talked to him? He was a hell of a guy.”

Captain Sartain was indeed, a hell of a guy. His philosophy of command was one built on respect for character not status or rank. In short, the respect due every decent human being.

In his 2005 interviews Sartain was asked if he had a particular philosophy or style of command. “Yeah,” he answered. “I definitely did. We had a terrific group of noncoms. Sergeants and corporals. A real terrific group. I had regular, routine meetings with them. It got to where they could say what they wanted to. A-Battery was terrific because of the NCOs and the personnel. The officers could screw it up but the backbone of A-Battery was the personnel, the rank-and-file personnel. I guess I had the right attitude to work through them and with them. I guess the men knew that. I was very fortunate, very fortunate.”

Sartain took a few more puffs, then added a postscript, “Sometimes, in England or Ireland,” he recalled, “You’d get these guys who’d go off on a bender. In the morning they wouldn’t be at roll call. We’d mark the morning report as all present and accounted for. Well accounted for could mean a lot of things. If they didn’t show up by ten o’clock, then I’d send off a couple of guys in a jeep to go look for them. We’d find them because they were sleeping it off somewhere, but they were good guys. I’d tell their sergeants to give them some extra duty and let it go.”

Captain Charles Sartain fought in the major campaigns of Naples-Foggia, Normandy, Holland, Ardennes, Rhineland, and Central Europe. His service was awarded with the Good Conduct Medal, Distinguished Merit Badge, European/African Middle Eastern Service Medal with six bronze service stars, Bronze Arrowhead, Air Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster, Silver Star, Dutch Bronze Lion, Belgian Fourragere, Glider Badge, Parachutist Badge, Presidential Unit Citation Badge, World War II Victory Ribbon and French Fourragere of the Croix De Guerre. (See below.)

General Order 13 and 126 - 1945

Award of Air Medal w/Oak Leaf Cluster

“For meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flights from 22 June 1944, to 8 July 1944, in Normandy. Captain Sartain distinguished himself by skillfully and successfully completing 35 sorties as an artillery observer in the adjustment, surveillance, and registration of artillery fire on enemy installations And in front line reconnaissance during the period of combat. On all these missions Captain Sartain was exposed to enemy antiaircraft fire as well as occasional attacks from fighter planes. Entered military service from Baton Rouge, Louisiana.”

“Charles L. Sartain, Jr. 0466381, Captain, 319 glider Field Artillery Battalion, for gallantry in action, 25th September 1944, near Holland. The battalion assistant S-3 on routine inspection tour of forward artillery Ops in the area observed three squads of German infantry moving in and taking positions to cut off a friendly infantry position through heavy small arms fire and found the position under attack by a superior number of the enemy, supported by tanks and flamethrowers. The battalion S-3 assumed command, while Captain Sartain, with the utmost coolness and courage, went about reorganizing the position, passing among the men time after time, giving encouragement and instruction to each individual soldier. His courage and devotion to duty, in utter disregard of his personal safety, was a great factor in halting the attack and holding the position until the arrival of reinforcements and resupply of ammunition. His courage, coolness, and conduct under fire was an example and inspiration to all the men in the position and exemplified the best traditions of the service. Entered the military service from Baton Rouge, Louisiana.”

“Charles L. Sartain, Captain (then 1st Lt.), 319th GFAB. For meritorious achievement while participating on aerial flights from 17th June 1944 to 3rd July 1944, in France. Captain Sartain distinguished himself by skillfully and successfully completing 35 sorties as an artillery observer in the adjustment, surveillance, and recognition of artillery fire on enemy installations and in front line reconnaissance during the period of combat. On all of these missions Captain Sartain was exposed to enemy anti-aircraft fire, as well as occasional attacks from enemy fighter planes. Entered military service from Baton Rouge, Louisiana.”

“Pursuant to authority contained in Netherland’s decree number 31, 8 October, 1945, announcement is made of the award of the Bronze Lion to Captain Charles L. Sartain, Jr., who distinguished himself during the 82nd Airborne Division operations in the area of Nijmegen in the period from 17 September to 4 October, 1944, by doing particularly gallant and tactful deeds and setting in every respect a praiseworthy example in very difficult circumstances.”

“While serving as the Alpha Battery Commander of the 319th Glider Field Artillery Regiment, when he took command of E co. 325 Paratroopers. Captain Sartain personally directed and led the group’s defense of finger ridge after encountering an attack by German armored forces on September 24th, 1944. His leadership save the Company of 82nd Paratroopers in the position as well as repelled three successive enemy armored and flame thrower attacks, allowing friendly forces to hold the critical high ground of the Divisions’s southeast flank. As a direct result of his efforts, E Co 325th GIR successfully held the strategic position of Finger Ridge for the duration of the campaign. For his exemplary service, he was awarded the Silver Star.”

In 2021 Captain Charles L. Sartain Jr., was elected into the “All American Hall of Fame.”

Postwar life

Like so many other discharged GIs, Charles Sartain first had a homecoming with his parents in Baton Rouge, followed immediately by a trip to be reunited with his fiance, Margaret Huddleston, in Shreveport. The couple were married on November 30th, 1945. Colonel Todd, Major Silvey, Chaplain Reid and most of the other newly stateside officers of the old 319th were invited and a number attended.

Mr. & Mrs. Charles Sartain - Nov. ‘45

The newlyweds rented a flat in Baton Rouge and Sartain resumed his study of the law. By taking summer school classes, he graduated with a JD degree from LSU in June 1948.

In the meantime, Sartain was without income. To ease the financial stress, he signed up with the Army’s Inactive-Reserve for its $70 monthly stipend. “It was very, very inactive,” he later recalled. “We met once a month doing problems with maps, things like that. It was a waste of time really.” Sartain also learned that by declining a Major’s commission in the reserve he would be eligible for a $400 bonus as a field officer. Considering he had no aspirations of staying in the military Sartain made the decision to remain a Captain and collect the money.

Korean conflict

In March 1951, Sartain’s entire inactive reserve unit was called up for the Korean War. He was not pleased to be back in the active military. It interrupted his struggling law career, but he’d signed the papers and was obligated. Sent once again to Ft. Sill, Oklahoma, Sartain found himself an Airborne Artillery Instructor. Though there were aspects of life at Ft. Sill which were appealing much about the military autocracy rankled him. Moreover, having once declined a Major’s rank the Army passed him up for promotion, advancing other Captains with less seniority over him. By the time he was discharged in September 1952, Sartain, never one “to go along to get along,” had his fill of the military machine.

Practicing Law

Attorney Charles Sartain

Now returned to civilian life Sartain devoted himself to his law practice. While he built up his own practice Sartain was also affiliated with a firm which, according to Sartain, “were labor oriented. They represented all the labor unions. Well, my inclination and interest were totally opposite. I didn’t care about getting called at eleven o’clock or midnight to get some guy out of jail who’d just poured sugar in his boss’s tank, you know what I mean? I didn’t want any of that because I didn’t want some drunk bastard calling me at three o’clock in the morning to get him out of jail. That happened to me one time. Telephone rang, it was about two thirty in the morning, this guy says this is so and so and I belong to such and such local. I’m here in jail. Come get me out. I said, well you stupid son of a bitch, if I was to come get you they’d put us both in jail at this hour of the morning. I’ll see you around eight-thirty. And I did.” “I loved the practice of law, but I got really tired of being a lawyer, I really did. I was going back to the office on Saturday mornings, Sunday afternoons, just to catch up with my work. I was in court two full days a week. It got to be a real hassle,” remembered Sartain.

Sartain as a Jurist

In 1960, Sartain was approached by the Louisiana Bar Association, asking him to seek election as judge of the Family Court in East Baton Rouge Parish. The idea had been a growing ambition for some time, and he accepted the offer. On November 10th, 1960, he was sworn in as judge of the Family Court. “When I got to be judge that changed my attitude,” he later explained, “My gut feeling was that when I put that black robe on,, I had to be open-minded and I had to be fair. People would come in and the bailiff would have whites sit on one side and blacks on the other side. I thought, we are in a court of law. You know that’s wrong, that isn’t right. So, I was not going to separate the races in the courtroom, I was not going to do it. I told my bailiff when somebody comes in the courtroom, they should take their seat where they wanted to. He got upset and quit which was OK with me. I would have fired him anyway.”

“when I put that black robe on I had to be open-minded and I had to be fair.” - Judge Charles Sartain

In the early 1960s the subject of segregation was the most controversial and divisive issue since the Civil War. Dodging the question would have been the expedient political, social, and professional thing for Judge Sartain to do. Instead, he faced the issue head on by bringing a screwdriver to the courthouse and, early one morning, taking down the “Whites” only sign above the drinking fountain. “The ladies in the record room across the hall had an absolute fit. I knew that but I just felt like, well, it wasn’t their water fountain to start with.”

Perhaps Sartain remembered his rash proposal to make coffee and biscuits available to the enlisted men during their daily training at Ft. Bragg in 1942. He was a naive 2nd Lieutenant then and his effort backfired. The result was that nobody got coffee or biscuits. If he were to address two-hundred years of discrimination it had to be handled carefully. “I was determined to hire black probation officers,” he recalled. “So, I did, but I had to wait about two years to do it until after I had talked to every Boy Scout troop, every Sunday school class, every high school in the city, till I thought I was personally strong enough to withstand the storm. I hired two black probation officers and then later on I hired another one. By the time I left the family court it was about forty percent integrated.”

Though he’d taken the initiative in desegregating Louisiana’s courts, Sartain remained modest about the accomplishment. “I wasn’t a crusader,” he said. “I never have gotten out on street corners and all of that foolishness. It’s just that there isn’t any reason why an individual, black or white, can’t be treated with respect.”

Court of Appeals

After a half dozen years presiding over the unfortunate and often sordid details of Family Court the job became burdensome. Judge Sartain explained his decision to move on as an Appellate Court Judge this way, “I liked it alright,” he said, “but it got really tiresome, you know, messy stuff. I’d had all the domestic squabbles I could take. I was either going to go back to practicing law or run for the court of appeals.”

In 1966, an opportunity to do just that came around. Feeling his chances were good Sartain ran for the unexpired term of a deceased judge and was elected to the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals in June of that year. “When it was time for somebody to run for Court of Appeals, I was head and shoulders above everybody. I’d kept my contacts. I’d hired my two black probation officers by that time, then we’d hired two more. So, I was in solid with the black vote you know, and the guys that were going to run against me I told them go ahead and run. I got elected with opposition. First to a two-year term of unexpired vacancy then secondly to a full twelve-year term. It got to where they couldn’t run anybody against me.”

Over the following fourteen years Judge Sartain continued his judicial duties and supplemented them with a full schedule of service in community and church affairs. He was a member of the Masonic Order and a founder of Acacia, an associated fraternity. The Sartain girls, Lynn and Charlotte, grew up to marry lawyers themselves, a situation which the Judge jokingly complained about when he said, “Too many damn lawyers in the family. We need some plumbers! Sink gets clogged up, nobody knows what to do.”

Summation

Many of the men who survived their time in the 319th, came through with not just physical wounds and injuries, but also with less clearly defined but just as enduring marks of the war upon them. These ranged from neurotic reactions to combat such as hyper-reactivity and startle responses, emotional volatility, intrusive memories of the war, and interpersonal difficulties, to insomnia, alcoholism, violence, and intractable chain-smoking. For most there were also more subtle changes, loss of ideals and the world-weary cynicism of those who have seen too much of life’s uglier side, too quickly. Though most of these symptoms dissipated over time traces of some or all remained for many.

All American Hall of Fame - 2021

While Judge Sartain exhibited some bitterness about the Army as an institution what came through most clearly was a firm belief that civil society could be made better. Human beings were innately good if given the opportunity to realize their potential. We each have a responsibility to contribute toward that end when and where it was within our power to do so.

Judge Sartain’s 2005 interview was perhaps his last statement as battery commander. He spoke slowly, choosing each word carefully. “Other than my parents, wife, children, grandchildren, and sons-in-law,” he said, “I can truthfully say that the best thing that ever happened to me were my days with A-Battery, the 319th and the 82nd. Even though it was sixty-five years ago, there is never a day that I don't think about those days. It just means more and more. A-Battery was a special group every last one of them. To feel that I had their respect is a cherished memory. Now there’s a lot more behind me than ahead, but when I think about it all and say my little prayer, I just thank goodness.”

Charles Lenton Sartain, Jr., 97, died November 15, 2017. God Bless this hero.

The following video was produced in 2013 in anticipation of a talk given by author, Joseph Covais, for members of the 82nd Airborne at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Judge Sartain would have been the best guest speaker, instead this interview was conducted. He spoke of his military career with the 319th Glider Field Artillery in World War 2 and war-time memories.

Photographic illustrations included were taken from actual World War 2 photos of the men of the 319th Glider Field Artillery.

STL Archive Records