John Manning

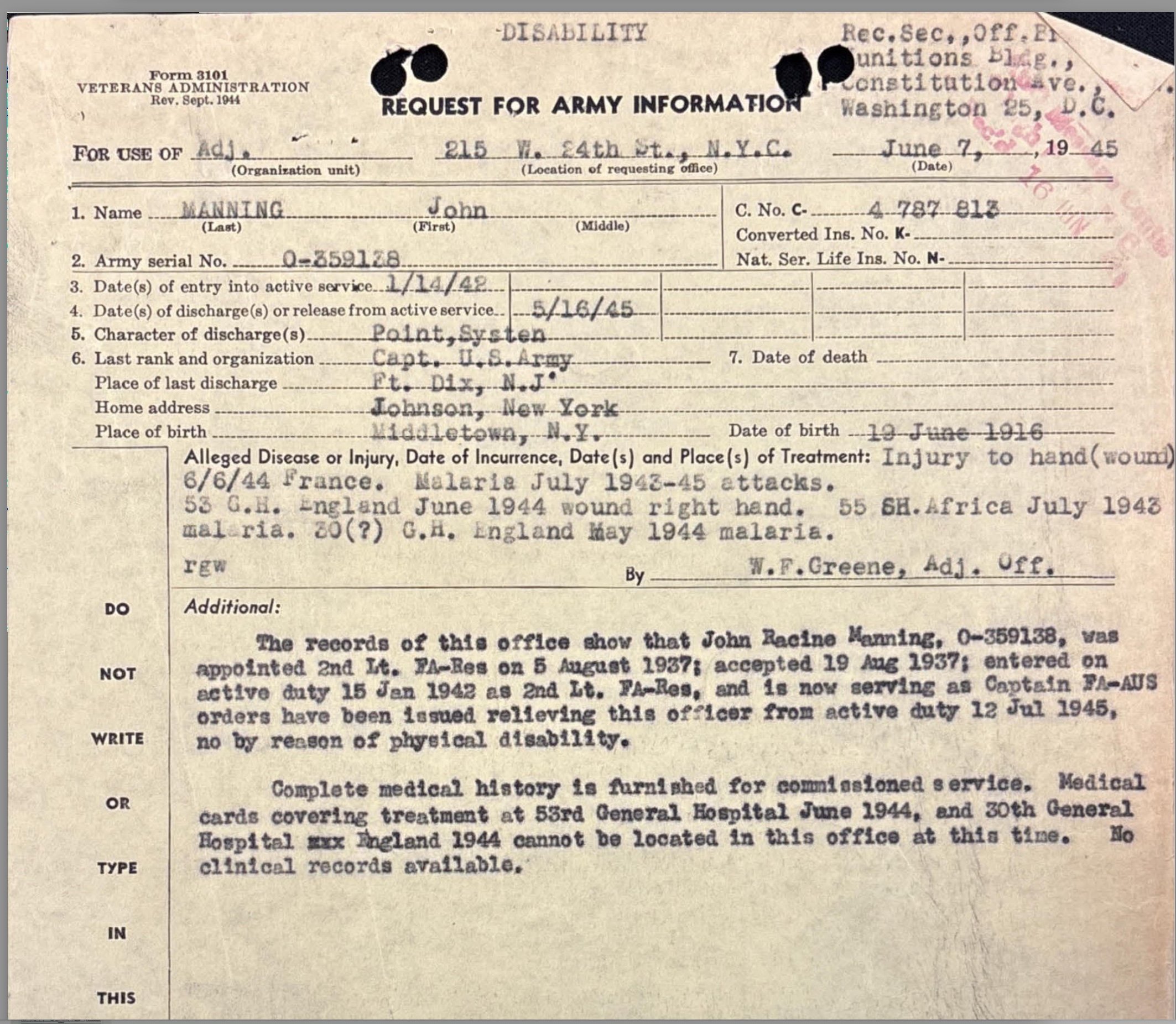

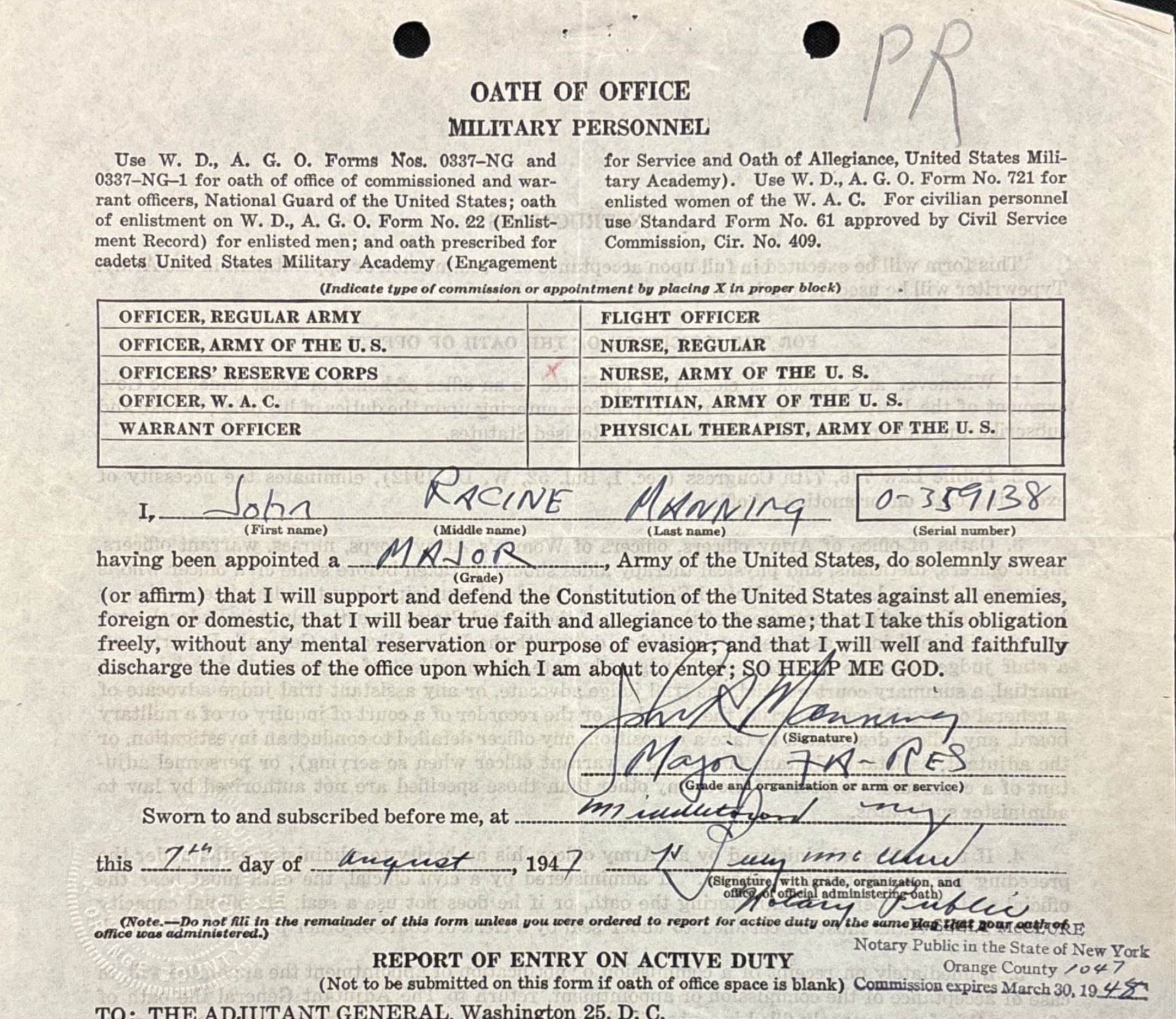

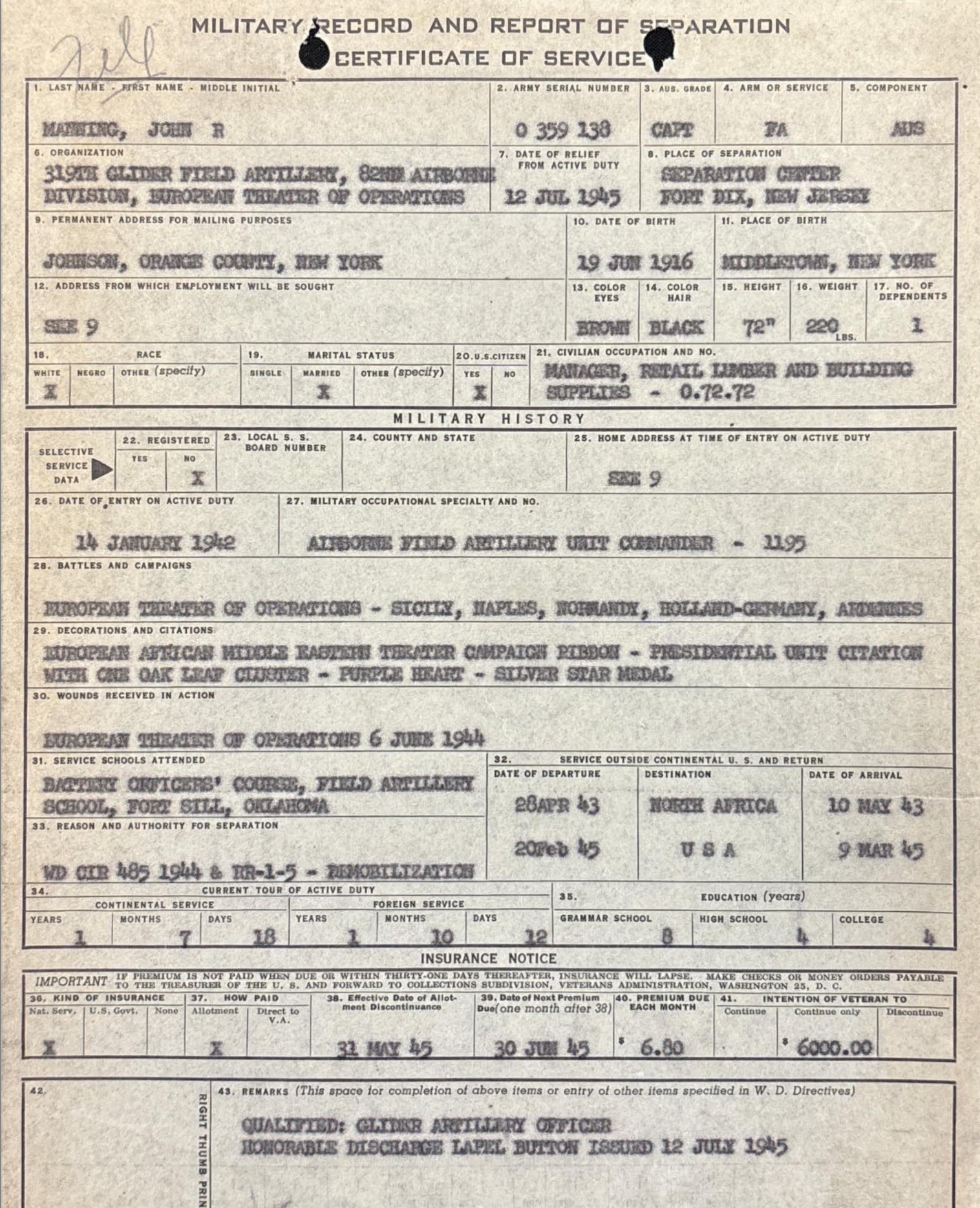

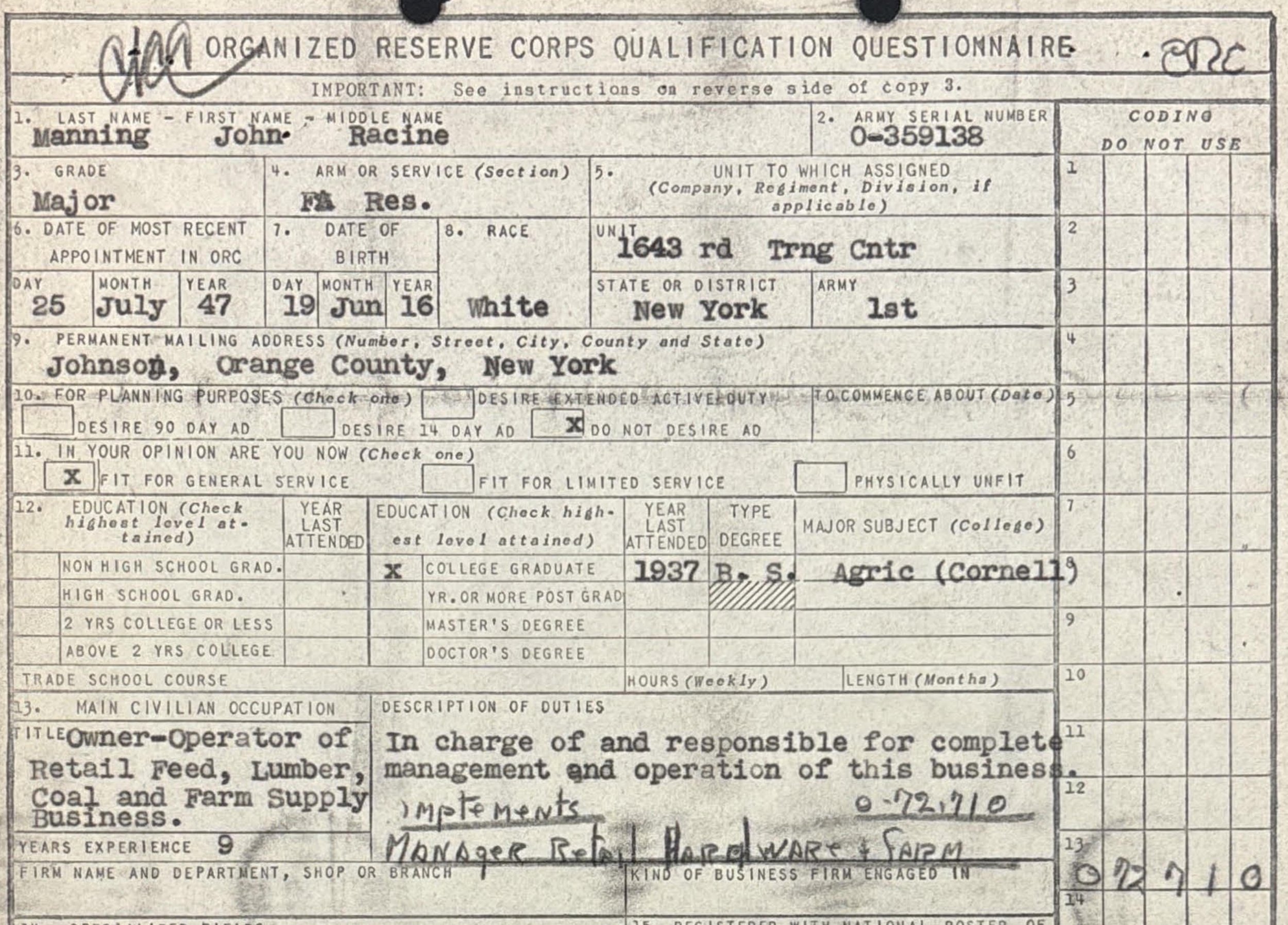

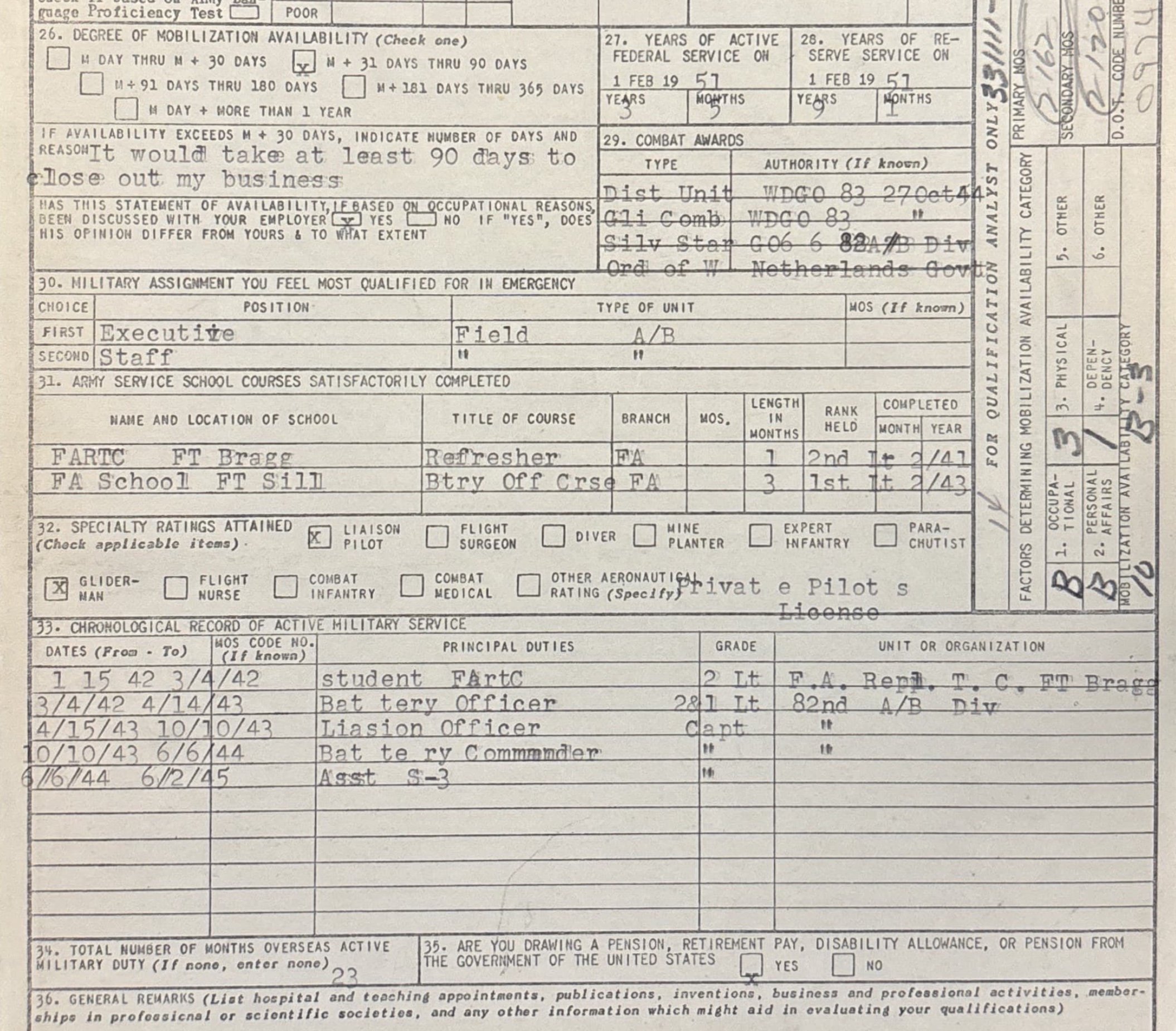

ASN:O-359138

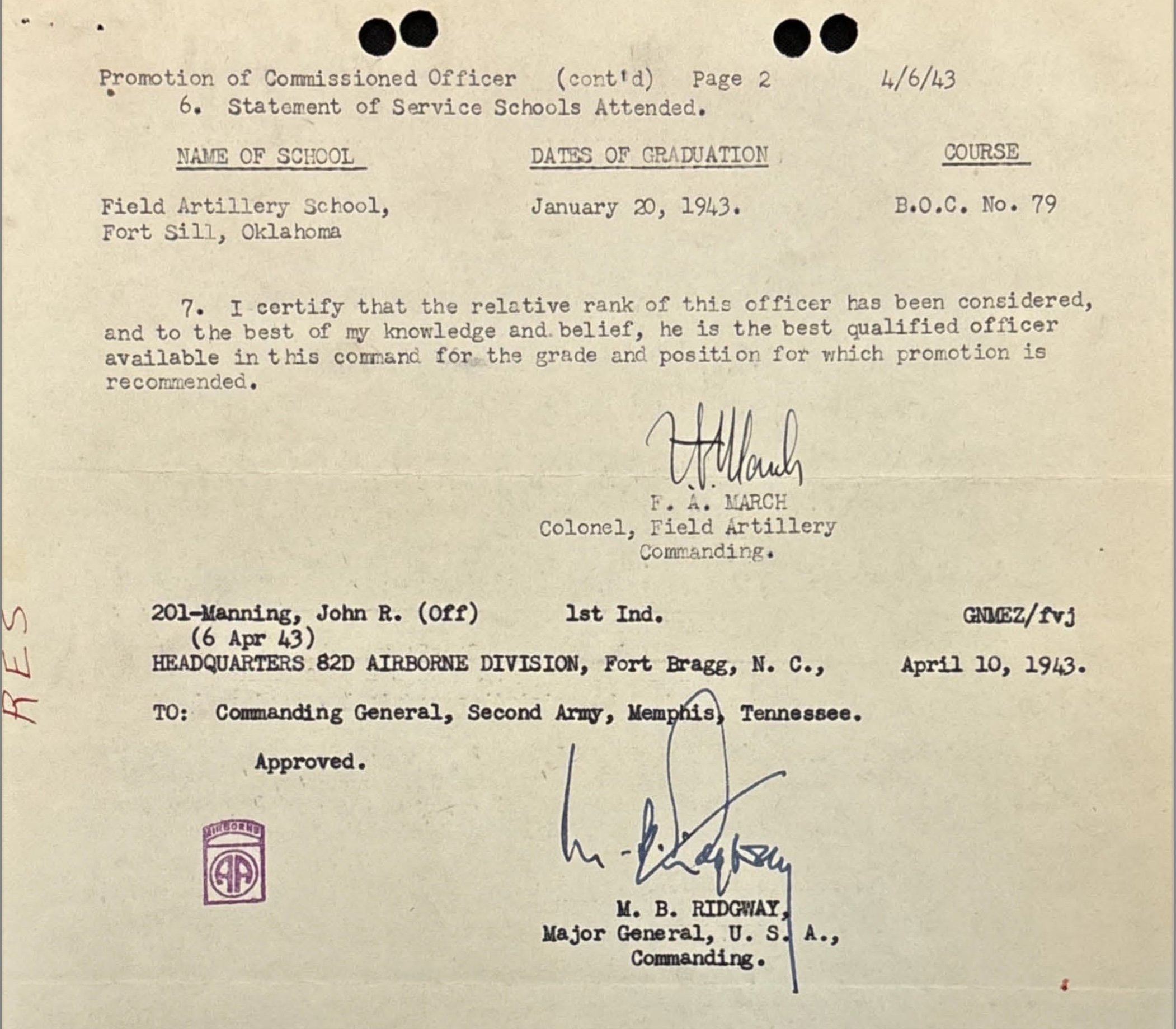

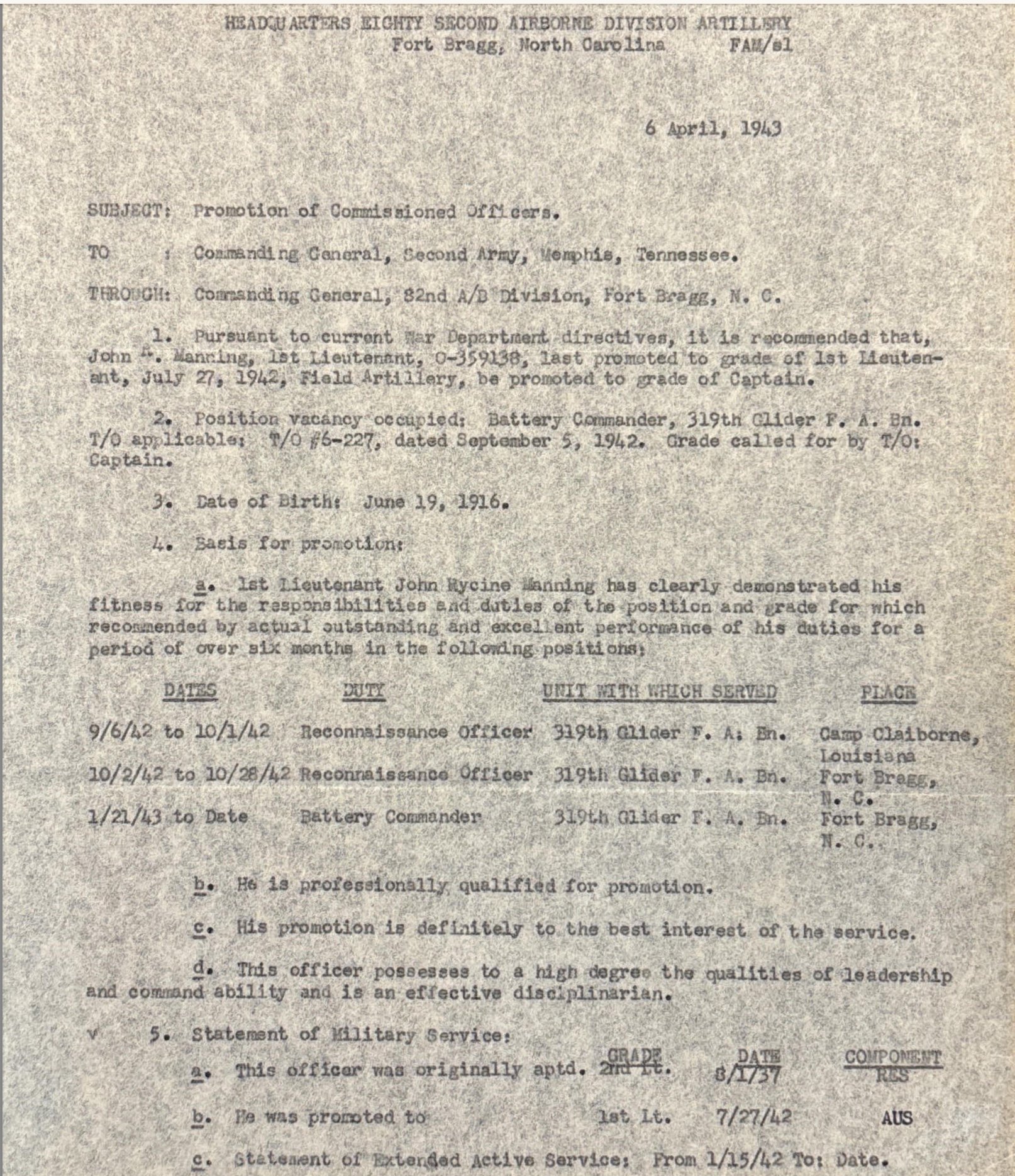

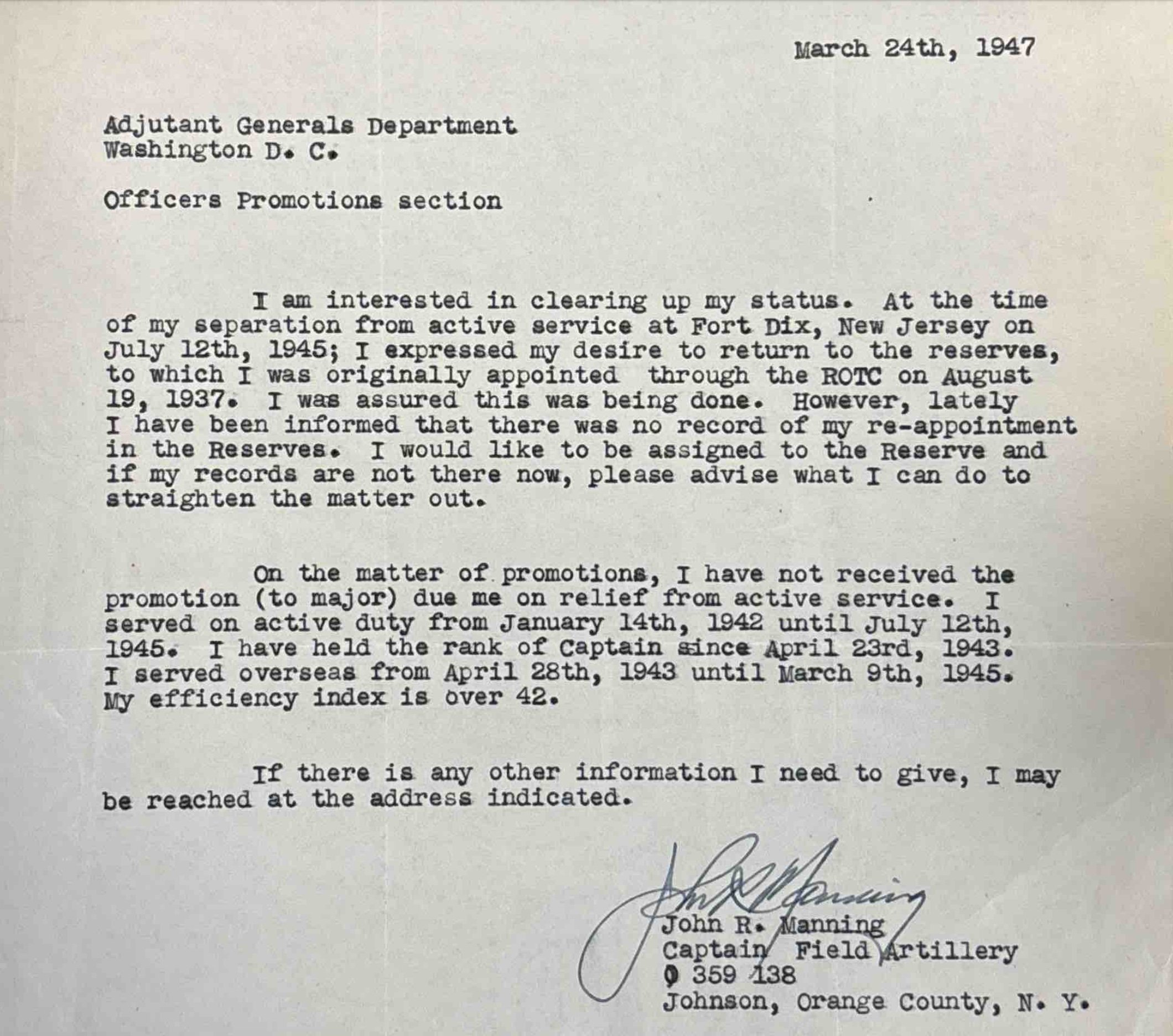

Captain John Manning

A MEMOIR

On December 8, 1941 I (John Manning) received my telegram to report to active duty at the Field Artillery Replacement center at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. This was a bitter blow to my parents and their plans to retire. Looking back on the war years, I often think how bleak it was for those left at home. True, the troops faced many dangers, but, if they survived, they had memorable experiences.

Fort Bragg

Fort Bragg was a large induction center at which all the newcomers were given 13 weeks of basic training and made ready for eventual assignment to permanent units. The strict physical training was fun for me – and the camradrie of many other young men in similar straits made the time pass easily.

My permanent assignment was to the Artillery of the 82nd Division. This was a unit with a past history as being the Division of Sergeant York, one of the individual heros of World War I. We had gone through about 10 weeks of re-training as a Unit, when the camp erupted with brass and we were assembled for a special announcement. Generals Bradley, Ridgeway, and Taylor gave us a big pep talk and broke the news that the 82nd Division was to become 2 airborne divisions – the 82nd and the 101st. We all were congratulated on the selection and told we could either jump out of airplanes or ride in gliders towed behind to be dropped inside enemy lines. At first, they put a weight limit on parachutists of 175-180 lbs. I couldn’t make this, and must say I was a bit relieved. The gliders seemed to be somewhat the better of two poor risks.

Training & Glider Flights

We trained intensively, mostly as ground troops with minimal equipment and support. It was thought that our airborne missions would usually leave us in this state – one time the “planned thinking” was correct. My assignment was to the 319th Glider Field Artillery Battalion, Colonel Bertcsh commanding. Our colonel was a West Pointer with definite ideas. Although we growled long and loud behind his back, he probably did much to make us into soldiers.

Glider training flights became a regular part of our work. I had thought that I might be prone to airsickness, but took to the bouncing, swaying, canvas and pipe birds quite well. A major problem in the training was in learning how to pack material and equipment in the gliders so that it would stay in place. Our time was also taken up by artillery practice sessions, and overnight marches with a full pack.

I related well to the men, and was soon an executive officer in “B” Battery. Perhaps I related too well – particularly when it came to being permissive. We had an inspection scheduled by some brass from 3rd Army, one time, and I earned a reprimand from our Colonel. We were told to line up along the edge of the parade ground and be ready when the inspecting party arrived. Naturally, it has to be the third day of continuing rain. We waited for about 90 minutes. I thought the men should have a break and I allowed them to break ranks. Finally the brass arrived and I hastily re-formed the battery. I had not noticed that many of the men had taken off their helmets while on break and used them as stools to rest on. When the inspectors came down the ranks of all these wet soldiers with mud circles on top of their helmets – they were not amused.

Camp Claiborne

As Bragg was an induction center, we were moved on to Camp Claiborne, Louisiana as soon as our Division was considered to have "jelled" as a unit. Our training continued in the same vein on the different turf. I had become Battalion Motor Officer. One of the duties I remember most vividly was the training of drivers. I never realized that so many men did not know the basics of driving a car, much less a 2 1/2 ton truck. I rode on more running boards, and listened to more gear grinding than anyone person should have to do in a life time. We finally developed some excellent drivers (many moved on from our outfit, and I met them overseas driving the "Red Ball"). One fun part of the training was "difficult traction" classes. It was necessary to develop capabilities of driving straight across almost any kind of terrain - for places where roads did not exist. We forded streams, winched up banks, corduroyed over mud holes, and had ourselves a great time.

The Colonel thought that he should have a Battalion Recreation officer. He appointed me to organize a jazz band. No budget was forthcoming and I had to wing it with pick-up personnel and instruments scrounged from unlikely places. Our best tunes were the Tiger Rag and the Beer Barrel Polka.

When the time came for us to head back to Bragg and get ready for shipment overseas, my Motor Officer assignment proved a break. Colonel Bertsch had a LaSalle car of which he was very possessive. Orders called for him to be on the troop train with the battalion. He selected me to nurse that car from Claiborne to Bragg. It was a break to not hit the trains again, but I was a bit nervous until he finally accepted delivery at Bragg.

I had been fortunate in that my wife Marg was able to come down to Bragg and to Claiborne. We were permitted to rent accommodations off base, along with various other young officers. These living conditions improved our morale a lot, I think.

Return to Fort Bragg

When we returned to Bragg, I was one of the officers selected to go to Field Officers Training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Marg was allowed to be with me and we located an apartment just outside the base. This was an intensive course in Field Artillery practice, procedures and well instructed.

Back to Bragg and to preparing for overseas. Marg left for home soon after we reached Bragg. She drove herself home (we still had the Chrysler dad had given us as a wedding gift). Her overnight stay enroute was in Richmond, Virginia.

My assignment had changed back to being an executive officer for "B" Battery - under Bob Cargile. Competition was quite sharp between the battery commanders and between the battalions, as to how efficient they could appear to the Division brass. When the day came to load all the equipment we had crated - howitzers, storage units, trailers, etc. - we were told where the railroad cars were sided and that we were to get them loaded. One crane was available to load into the regular 2 1/2 ton trucks. Cargile did not have a high enough rank but that we would have to wait at least two days for our turn. I happened to think of a large flat bed trailer I had seen at Pope Airfield, adjacent to Bragg. We went over and talked to the driver and he agreed to help.

We had a battery of good working men. They found some pieces of pipe and some good sized planks. When the trailer showed up we slanted the planks up to the bed, pushed the pipes under the crates, and "gang pushed" the crates on to the truck. The truck being the same height as the rail cars, and no one having yet arrived with their loads, we pushed off level into the cars and were back having beer at the PX while the other guys worked.

Off to North Africa aboard the SS General Washington

Our "embarking" was a bit of a let down. Just another routine cramming onto a train - only this time all personnel and all equipment were on board. We took two days to arrive at Camp Deven, Massachusetts. Our stay there was very brief - about 6 hours later we were back on another train for the port of New York. There we loaded onto the "General Washington" - a re-furbished cruise ship. Our trip over the Atlantic was uneventful. Most of the time was spent trying to sort out the men for their staggered eating schedules, arrange some sort of activity to keep their minds off themselves, and catch a little shut-eye myself. I spent most of the spare time I had on the open stern deck watching the stars and the phosphorescence in the ships wake. Dr. Jules Hebert, a medic Captain, helped me get more acquainted with the constellations - which came in to use later on.

Casablanca & Oujda

We docked in Casablanca amidst wrecked docks and half-sunken vessels. The bivouac area was on the far side of the town so we started out our overseas life with a parade. After two days of getting organized, we were ready to head for our first assigned training camp at Oudja. My stint as Battalion Motor officer got me a gravy assignment. All of the troops were loaded into the old 40 & 8 transport rail cars which looked like the one we had seen pictures of from World War 1. (40 Horses - 8 Men)

There was no transportation for the vehicles and battery equipment so yours truly was ordered to head up a convoy and drive to Oudja. It was a very interesting experience. We drove through Rabat, Mekness, Fez, Saidia, and various other towns; got a chance to visit a beach on the Mediterranean Sea, see many facets of the countryside, and even do some shopping. At Saidia we unknowingly infringed on General Eisenhower at one of his R & R spots.

Oujda was a big, big open plain as far as we were concerned. The town itself was quite small, and was kept off limits. One of the things I remember vividly about that location was the hauling of stones from the hills and placing them in rows to line out the walks and roads of the camps. This particularly ground on me after picking stones off of fields back home. One of the other duties which appeared hard to understand was the necessary catering to the Commanding Officers. Each one tried to outdo the next one as to having special shower facilities, patio areas by their tents, etc. Very necessary for the war effort. My assignment as Convoy Officer had put me on Battalion staff and I was always getting the word as to how some of these special projects should be implemented.

We did do quite a bit of training with the Infantry we were to support. I was Liaison Officer for the firing missions and was able to put to use my expanded knowledge of the constellations when we were released by the Infantry Colonel at midnight some 5 to 10 miles from our camp. It was often better to travel over the plain at night than to wait for the heat of the morning. We were often bumping into wandering Bedouins, but never had any problems. Their attitude was best expressed by the reaction to some of our artillery round which landed in one of their camps. We went over to assess the damage and make reparations, and were told we would have to pay for the goats and sheep killed; but no concern was expressed for the loss of two women.

Kairouan (the City of the Dead)

After five or six weeks at this camp we were assembled for a full blown air-borne operation. We were to move from Oudja to Kairouan using planes for the parachutists and gliders for us. The parachutist went first and we were told later that they had made a text book operation of it. When it came time for the gliders to move we were headed into a blinding sand storm. One hasn't lived until one rides in a flimsy pipe and canvas glider staring out at a rope which disappears into a black cloud and seems to have a life of its own. Suffice it to say that we did all finally arrive at our destination. Kairouan (the City of the Dead) was the cemetery town for quite a portion of the surrounding countryside. All the graves were mounds above ground level, and all has been fitted with holes for the souls of the departed to escape through. The atmosphere in Kairouan was quite heavy.

Our camp area here was in olive groves. Each grove was surrounded by a cactus hedge fence. The cactus produced a prickly pear which was very delicious. It was at this location that I found out my dress uniform had been completely eaten up by crickets. I had kept them in a bag under my jerri-can bed and had felt I was being very efficient.

At this location we got word from higher up that the 319th was to be changed to a 3 battery battalion. This was to be accomplished as much as possible by reducing the size of various portions of the battalion in general becoming a leaner organization. It was an ideal opportunity for the Battery Commanders to shed the trouble makers and goof-offs from their ranks. We did get some new officers from a replacement center and a few men. After the re-assignments had been completed I was informed that I was to be the commander of the new Battery "C". One Charles Lenton Sartain, one of the replacement officers, was to be my executive officer. Charlie and I took it as a challenge and worked hard at developing an esprit de corps in our battery. Many of the men were odd-balls in many ways, but they were tough and could work. In the long run we were quite successful.

Tunis to Bizerte - headed for the invasion of Sicily.

After a period of training at Kairouan, we went by truck convoy through Tunis to Bizerte - headed for the invasion of Sicily. At Bizerte we camped on the shores of the Sea - naturally, yours truly insisted on pitching the officer’s tent on the highest and windiest bluff - everything tasted like sand because it was sand.

Our first contact with war operations consisted in ducking the dropping flak from our own anti-aircraft batteries which were supposedly protecting us from German attack. After two days we were informed that our side had lost so many transport planes that there were not any left for us. We were to by-pass Sicily and land at Salerno by LCI (Landing Craft Infantry) and LST. (Landing Ship Tank)

Each Battery Commander had his headquarters group assembled and we were loaded on a LCI and set out for Italy. Off the coast we had a rendezvous with the Command Ship of the invasion operation. I forgot the name of the ship, but it was almost like walking down the streets of a small city back home. They had shops of every description. Seeing the ship and all these things after our time on the plains of North Africa almost made us forget to attend the briefings.

The beach at Maori, Italy

We proceeded to the beach at Maori about 10 P.M. The LCI's are designed to push their prows up close to the beach and drop down two stair-like runways - one on either side of the ship - for rapid disembarking. We did not have to be pushed! Everyone made it across the sand beach to a large retaining wall in record time. No opposition! We gradually felt our way across the highway and into some garden-vineyard areas. After everyone was accounted for we decided to wait for morning to assess the situation. In the AM I found our "C" battery group was cozily nestled up against a sturdy pig-sty. That day was spent in familiarizing ourselves with our surroundings and orienting ourselves on the map. Still no sign of any opposition.

That night the LST's were to come in and bring our vehicles, howitzers, ammunition, and other supplies. They arrived on schedule about 4 AM and we set them up in selected holding areas while we took some jeeps and forward parties to select the battery locations. The road went straight in from the beach and up a valley along side a mountain called Montefiore (Mountain of Fire) - as it has at one time been the location of many small volcanoes. "A" battery had the senior commander and he selected a site near the top of the valley. "B" battery was next in seniority and he selected a quite level spot half way up. We had to keep looking. I finally convinced the others that the best we could do was a hillside vineyard part way between the other two.

We had to work our way through bodies to get our posts set up

Our location was right at a bend of the road where a spring fed down from the mountain. At the roadside a watering trough and covered rest area had been constructed many years ago. From the rear of this area a steep path wound up the mountainside. We used this route to get to our observation posts on the top of the ridge, from which to direct the fire of the batteries. Just before we arrived at the observation post area it had been over run in a surprise raid - we had to work our way through bodies to get our posts set up.

The former volcanic character of the mountain worked in our favor - the craters were not too steep or deep, and made for very good foxholes. The entire top of the ridge was lava-like granules and made for easy digging when we needed to. I remember establishing a foxhole for myself on our side of the ridge, wrapping up in a blanket at the bottom of the hole and going to sleep for the night. In the morning, I noticed something draping over the edge of the hole. Thankfully, I moved cautiously to see what was going on. In the night we had been sent some Gurkhas (soldiers from Nepal) as reinforcements, and I was being guarded by one - with one of the longest knives I had seen yet! We were to find that they were very efficient soldiers.

The 105's had 7 powder bags in each shell

We took turns at the OP - keeping in shape climbing up and down the trail. "C" Battery got a large number of the firing assignments as our odd-ball battery location turned out to be the most advantageous relative to the target areas. One of the problems we tried to solve was being able to hit the target areas on the forward slope. We got so we could actually see the projectiles sail over our heads as we were so high above the battery location. Sartain came up with the thought that we might be able to drop the rounds closer to the ridge by removing some of the powder. The bags were of different sizes, so we had lots of possibilities to work with. We were successful to some extent, but did not perfect the exercise to the level Colonel Bertcsh expected - he would have liked full charts of powder selections and resultant ranges!

We had a wide valley area of targets, including vehicle parks, troop concentrations, and highways. Our presence became a problem to the enemy and they got quite active with counter fire. Somehow, it became possible to endure their artillery, but when the multi-barreled rockets started it was a different story. We tried to target the rocket launchers, but they were mobile and were kept parked under bridges or overpasses between firings. We were blessed with some replacement officers who had to take turns at the OP - One stood up and focused his glasses on a rocket launcher location. They spotted him and we had to carry him off on a stretcher.

The infantry we were supporting there were the Rangers - a tough, well disciplined outfit

The infantry we were supporting there were the Rangers - a tough, well disciplined outfit. I well remember when "B" battery dropped a short round on our part of the turf - Captain Sam of the Rangers came over to me and told me very succinctly what my fate would be if one of those rounds hurt some one.

One interesting experience was my contact with a British Naval gunnery officer. He had been sent to act as an observer for one of their large warships in Salerno Bay. He and I worked out patterns of targets and he took over on the ones we could not nullify. It was very impressive to hear those big rounds come whistling in. He gave me his issue winter coat when he returned to ship. It served me very well through the war and afterwards.

We worked Montifiore for about three weeks. Sartain, as executive officer, was in charge of the firing battery and got to know the owner of the vineyard we had usurped. He accepted an invitation for he and I to have dinner at the Villa with the owner and his family. A very formal, but friendly, affair with real crystal, china, and silverware! A bit of a language barrier, but we all came through.

They had irrigation ditches going through the vineyard. They were wooden troughs buried in the ground and usually quite full of water from the roadside spring. We found that they also made quite convenient bathtubs, much to the amusement of the senorita working the vineyards!

I will never forget the view when we broke out on top

When it came time to break camp we were directed up the road to go over the ridge towards Naples. I will never forget the view when we broke out on top. The ridge was very narrow and it seemed like we were on a knife edge, and could see for miles in both directions. We moved rapidly into a suburb of Naples and re-grouped. We set up the batteries but did not fire.

The word came down that Naples had been secured and we were to go in and occupy the city. DivArty (Division Artillery) assigned Battery "C" the lead of the Artillery column because of our performance at Montifiore.

In Naples the city was divided into zones and districts. Our battery was given an area of the Vomero, a classy residential portion of the city - including the main night club. We took over a vacated estate - complete with a Lancia sedan - for Battery "C". I was able to set up an apartment for our officers at a nearby location. I kept the Lancia as my "command" car.

In Naples we were responsible for the operation of the night club, the "Orange Garden"

We were responsible for the operation of the night club, the "Orange Garden." Our landlady and a girl named Adrianna Cappocci were very instrumental in our getting the right contacts for that job. We endured a few air raids during our stay, but not much else. The populace was desperate for food. I remember seeing a skinny horse go down trying to pull a cart up one of the cobblestone hills - three hours later there was only a pile of bones. We provided food when we could spare it - a department of our battery which operated very efficiently due to a super-scrounger named Corporal Smith. He "assisted" in the off loading of many ships coming into the harbor.

It came our turn to push towards the north. The Anzio beachead had been started and some other front action was needed. Our goal was to secure a crossing over the river Volturno. We were integrated with some Brits - and continually had to wait while they made tea!

We lost some men at the Volturno River

We lost some men at the Volturno. Our positions were quite out in the open and received a fair amount of fire. There were no hills for OP's so we had to get right up into the front lines to direct fire. For battery "C" we chose the top story of a 3 storyail. It soon became a target in itself and we had to vacate quickly. My Lieutenant Fitzgerald was lost in the dash out. When we reached our "security" checkpoint we found that the entire squad had been knifed during the night. We continued to pound the mountain on the other side of the river with all the fire we could. When the infantry went across, they still found an awful lot of resistance. In the end we were able to hold the crossing but not the advance. Other troops came forward through our lines and we were returned to Naples.

We had a short time to rest and relax before we were to ship out. One of the places I had always heard of was the Isle of Capri. It is in Naples harbor. We bought a ride on a fishing boat and had a great time exploring Capri, especially the funicular railway, - I even took over a horse and carriage for our stay! When we came back to Naples we ate at a restaurant at dockside - I still don't know what type of sea food I ate - it tasted good in many ways but it seemed like it was walking down my throat.

We toured Pompeii and the Isle of Capri

Another side trip was to take some of the people who had been so helpful to us down to Pompeii to see some relatives and get some fresh vegetables. In return they gave us a tour of Pompeii. The old Lancia was quite well loaded on that trip.

We got our orders to board ship. The destination was to be Ireland - in preparation for the landings in France. I well remember pulling out of the Naples harbor late at night with Pompeii glowing in the background.

Our voyage to Belfast was a typical troop ship trip - too many people in too small quarters. My main memory of the trip is of PFC Silas Hogg - one of my men who was always in and out of trouble, but still a capable soldier. He got heavily involved in crap games on ship, and won heavily. He got concerned about having all that money and asked me to keep it - and not to let him argue me into giving it back to him. He was quite prophetic in his thinking. About two days later he was constantly at me to return his loot. I managed to keep it until we arrived in Belfast and then had it sent home to his family. It took a couple of months for him to settle down.

Belfast was a busy harbor

Belfast was a busy harbor - troop ships, war materiel transports, and destroyers crammed the ways. Truck convoys were awaiting us and we were soon on our way to Bellaghy - a small village about 45 miles to the southwest. There we were to be encamped on an estate property which had been assigned to the war effort. The grounds were randomly fitted with the ubiquitous Quonset Huts. We had had slight contact with them in Africa - but there it was too hot to consider them. Here they afforded good quarters. The closest town of any size was Ballymena. It was the site of the Adair Arms - a pub hotel which welcomed our business. For some reason the higher army authorities thought we should improve the morale of the troops by having a big dance. The manager of the Adair Arms introduced us to a lady named Dorothy Pearl Armstrong and her sister, as likely contacts to round up girls for a dance. As transportation was needed, Sartain and I were assigned as convoy officers. It is hard to think that you are seriously contributing to the war effort when you are in a jeep heading a three truck convoy loaded with girls across a dark moor. To compound the issue, a lone gunman with a rifle rose out of the mist and hailed us - turned out to be a representative of the Irish Republican Army. We finally arrived at a small airfield hangar which had been set aside for us. We got good marks from the troops for throwing a party.

After we got into our routine we went into intensive training - mostly long hikes in the area, and convoy trips to artillery ranges laid out in the moors. The moors were in the northern portion of North Ireland - near Londonderry. A very open, rural area lightly populated. We were never in the Republic of Ireland. Our travel was entirely by truck convoy - no airport facilities existed at our location. The training went well as to our use of our artillery pieces and as to coordination with other forces in the same training area.

The war seemed quite distant as long as we were in the training areas. However, after we had settled in, weekend leaves were given to go to Belfast (about 45 miles away) and we were subjected to blackouts, bombing raids, and scenes of devastation which were to become common to us later on. I seemed to always get the odd-ball battalion assignments. In this location I was appointed to form a battalion basketball team. Lets just say - we had fun for the short time we had.

Market Harborough and Lubenham

An Airborne Force needs to have access to airports and planes, and it became time for us to move down into England. We were stationed at Market Harborough and Lubenham - just south of Leicester in south central England. Our airport was at Cottesmoor. Here we (our battalion) took over an estate called Papillon Manor and a small hotel in Lubenham. Our training now included glider flights and parachute jumps - as exercises, not coordinated operations, as there was not enough room for extended operations. Our training was quite intense, but allowed for R&R trips into Market Harborough and Leicester. The English people were very cordial and supported the troops by sponsoring dance halls and special events. I did get to take a leave while here and took it to Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Loch Lomond in Scotland. It was a very welcome break, the Scots were also very cordial.

While in North Africa, I had contracted malaria and went through the "cure" and a stay in the hospital. In Market Harborough this came back on me and I had to repeat the treatment – intensive quinine, etc.

As the spring weather improved, our training intensified and we were alerted to the possibility of an attempted Channel crossing for the month of May. As usual, plans were changed and re-changed and we were finally moved to a tight security camp about June 1, 1944.

Individual names in the 319th-: Col. Bertsch, commanding officer; Maj. James Todd, executive officer; Major Jerry Wimberly S-3; Major Wilcoxon, S-2; Captain Connelly, battalion supply officer. Battery “A” (my command); Lieutenant Sartain, executive officer; Lieutenant Richard Carey; Lieutenant Robert Hulle. Also in the battalion were Captain Richard Rogers, commanding Headquarters Battery ( I had known him at Cornell); Captain Robert Cargile, commanding "B" Battery; Lieutenant Frank Poole (another friend from Cornell, whom I had served as Best Man at his wedding in Fort Bragg in the few months before we left); Lieutenant Radcliffe Simpson, a West Point graduate; Lieutenant Blank, Lieutenant Bourgoise, Lieutenant O'Brien, Lieutenant Rogge, Lieutenant Sharkey, and others who have faded from my memory. We had developed into a very close group. My old command Battery "C" had been dissolved and the battalion returned to the original composition of two firing batteries. I was given command of Battery "A".

Cottesmoor Airport was very efficient. The paratroops took off in their DC-3s during the night of June 5th; the Glider Infantry right behind them. The Glider Artillery was to take off in the late afternoon of June 6th. It was a sight to remember. The sky was like a 5 mile wide Thruway - jammed with planes, and planes with Gliders in tow. We were given the English Horsa plywood gliders as it was thought they could carry more cargo. It turned out they were also more clumsy and could drop like a rock when disconnected from the tow ship.

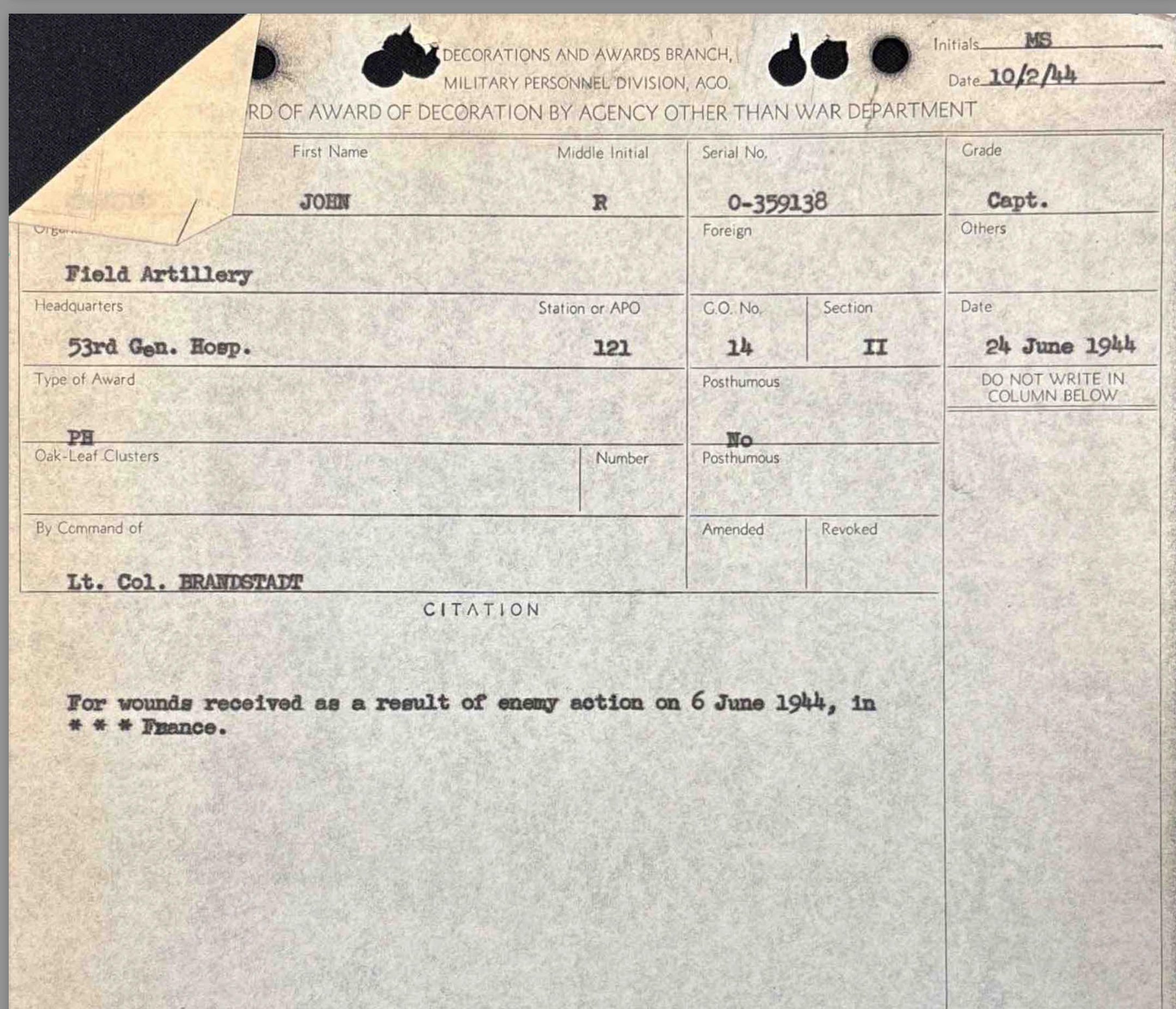

"White Cliffs of Dover"

It was almost dusk as we flew over the "White Cliffs of Dover." At any other time it would have been very scenic. Our only concern was for our survival to become part of the operation after landing. As we arrived over the French countryside we received quite a bit of flak and machine gun fire. Corporal Jameson, a medic I had requested from Captain Bedingfield, was taken out by the machine gun fire. The pilot of the tow plane was getting very uncomfortable. He told us to cut loose, or he would cut us loose at his end of the tow line. We complied quickly in order to preserve what maneuverability we could. The pilot and co-pilot asked me to take one of their watches and stand between them to count down the seconds for our glide in. These gliders land at 90 miles per hour with the brakes fully locked - and just run it out. We picked the largest field we could identify in our range of possibilities - hit it near dead center and were on a dead run for a row of big trees. We must have hit between two trunks. I came to on a pile of rubble still holding the watch. The pilot was hung up in one tree; the co-pilot was dead on the ground. I found my right hand to be cradling my partially disconnected thumb. Naturally, I bypassed my medical packet and wrapped the thumb in a dirty handkerchief. I dragged out my 45 Colt and tried to take charge. The enemy soldiers near us appeared to be confused and scared, so it was possible to assess our situation. Part of the cargo had been my Jeep. PFC Louis Sosa, my driver, had gone to sleep in the jeep on the way over the channel. He was completely unhurt. We had lost 4 other men besides Jameson, and 5 or 6 had injuries of various types. I found that I could hardly move my back. Sergeant Frank Marshall, my battery supply sergeant, took over for me and got the glider unloaded and the men formed up. We found ourselves near a farm lane which appeared to lead in the compass direction of St. Mere Eglise (our focus point) so we proceeded down it. We met up with Sergeant Johnson, my First Sergeant of Battery A and a group from his glider (which had landed quite smoothly). I set up a command post and we gradually rounded up about half of our battery. We lost Sergeant Wade and his crew in a tragic way - they had landed safely and were enroute to our area when an incoming glider landed right on top of them killing them all. By afternoon I was able to get my group to St. Mere Eglise and check in with Battalion. They decided that my right hand was useless and I should head out the medic evacuation route. Sartain took over the battery. During the ensuing action we were to lose Carey, Hulle, Simpson, and Poole from our officer cadre.

A mass of organized confusion

Some thoughts on war. The landing in Normandy was our first involvement at the middle of the main action. This is what we had been preparing for since the first days at Fort Bragg. It is terrifying! A mass of organized confusion. Ones dependence is heavily on oneself, even though your comrades in arms are supporting you as you are supporting them. Be it in hand-to-hand combat, or in supporting artillery fire. Death and injuries become almost mundane. One cannot help but feel deep sympathy for the civilians whose lives are on the line, and whose properties are being destroyed. I found that I survived by concentrating on each immediate problem, how to get to the next corner, or map location; making a schedule to get us through the next few hours; trying to secure our position through the night. As each problem was solved, or changed, we could measure our progress to the next plateau. We found, as we went through the various campaigns, this attitude served us well in moving forward, or in retreat. There is no time to worry about ones own mortality, or about the progress in the "big picture." One has to develop confidence in himself and in his immediate group, then after one step at a time the end of any given operation, suddenly arrives.

Normandy gave me the chance to experience the "Mash" experience first hand. One has to admire the medical personnel very much. The casualties at Normandy were extreme - mostly from the beach landings. My thumb injury received a quick stitch or two, a heavy dose of Sulfa, a bandage, and a ticket to be put on a hospital transport. The Transport was a large freighter which had brought over supplies for the landings. The side walls of the hull were hung with hammocks and we were each assigned one. While we waited for the ship to fill up we went through three bombing raids, but with only minor damage. The trip across the channel was a bit rough as the ship was riding quite high in the water. The seriously wounded men had a very hard time of it.

My thumb was re-attached

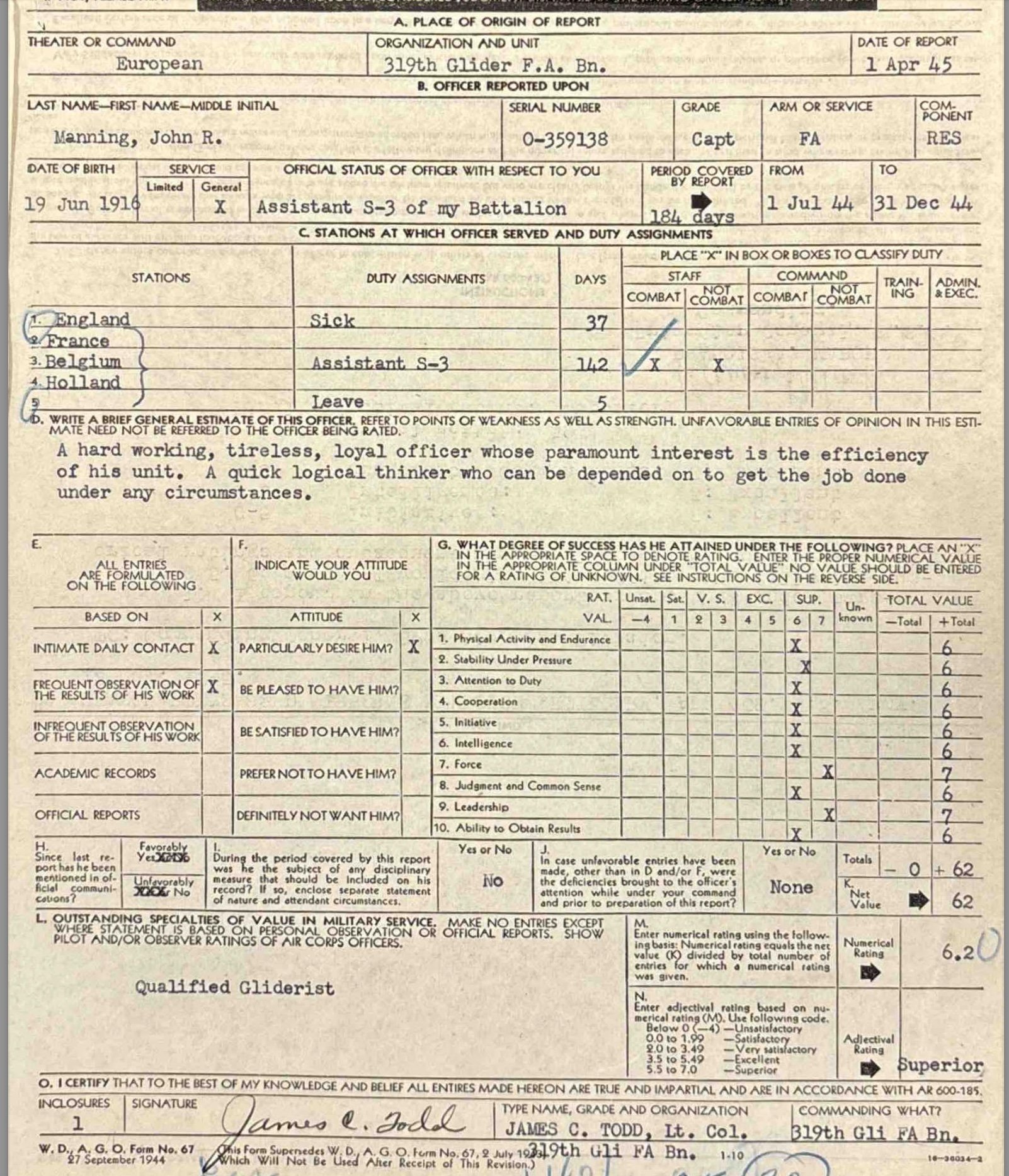

I ended up at a Field Hospital in Malvern in southwestern England. My thumb was re-attached and skin was grafted from my leg. The first graft did not take, but the second procedure was successful. My back injury seemed to be gradually improving. I was given some exercise therapy and extended rest. By wheedling information from Nurses Haines and Hagen (from Utica, NY), I was able to slip out of the hospital after a month. I had heard that the battalion was back at Lubenham, and wanted to make contact. I did not want to be re-assigned to a repo-depot. Colonel Todd (who had been promoted to command) pulled a few strings and got them to process my release back to the 319th when they felt I was ready for discharge. I was given the staff assignment of Assistant S-3, a post usually involving being the contact between the battalion and the forces we were supporting.

Our second stint at Market Harborough was a bit different, but still much of the same. We were quite efficient in our procedures, but continual practice was necessary. Now we had had a taste of what happened when we were committed to action. It made us more aware of improving our physical condition and our expertise.

Marg's brother De Hutchins was a driver on the Red Ball Express (the army terminology for the Quartermaster Corps). He looked me up one day as he was driving through with a load of bombs. I got him to put the truck in our motor park and he and I headed into Market Harborough to have a few beers and catch up on each other. De was a PFC, so army etiquette directed that we have our own party. As usual with De, it was a fun evening. I arranged a bed for him in my room. In the morning he got off early - thank goodness. Major Wilcoxson had made a spot investigation of the motor park during the evening and by lunch time was out to crucify whoever had allowed a truckload of bombs to be parked there.

"Market Garden"

By September we were again on the alert. The first operation got cancelled, then we became a part of the "Market Garden" operation dreamed up by Lord Montgomery. It was a plan to cross through the central portion of Holland and strike into Germany from the northwest - being the upper arm of a pincers movement, with General George Pattons army on the opposite arm from the south. As history records, our operation, as a whole, was only partially successful.

We were soon back at Cottesmoor. This time we were back in the US CG-4 Gliders we had originally trained in. Pilots were becoming scarce and we officers had to fill in as co-pilots. I never heard if any of us had to perform a landing, I don't think I would have been too adept! It was a daytime flight. As we approached the coast of Holland we could see the dikes and roadway systems very clearly - and they could see us! We received a lot of flak, but our glider only had superficial hits. It was very uncomfortable being such an obvious target. The daylight helped us make out the landmarks and we spotted a crossroad near Groesbeek and cut loose. Just in time, our tow plane went down in flames a few minutes later. We dropped into a large field in a rather steep glide and dug up about ten bushels of potatoes as we plowed our way to a stop. We unloaded the jeep, trailer and equipment and got on the road. No injuries in the flight or landing. The jeep driver was a recent assignment as far as I was concerned, and right then I found out I should have checked him out. As we sped down to an intersection, I pointed out the road it seemed to me we should take. Some paratroopers set up in a ditch called out that it was the wrong direction. At that point we found out we had no brakes, the driver had tied down the jeep in the glider and had pressed the brake lines against the axles and punctured them. A little fancy turning got us back on track.

I'm not much of a milk drinker, but I will always remember how good that tasted

My first contact with the Dutch people was shortly after. We stopped at a small house where I saw a woman in the yard to confirm our direction. She was very helpful and pulled a jug of milk up out of the well for refreshment. I'm not much of a milk drinker but I will always remember how good that tasted. A short ways down the road we found the battalion CP and started out to help find everyone. All were soon accounted for except for Connelly - his glider had gone past the drop area into enemy lines. Fortunately he was able to find his way back within a couple of days.

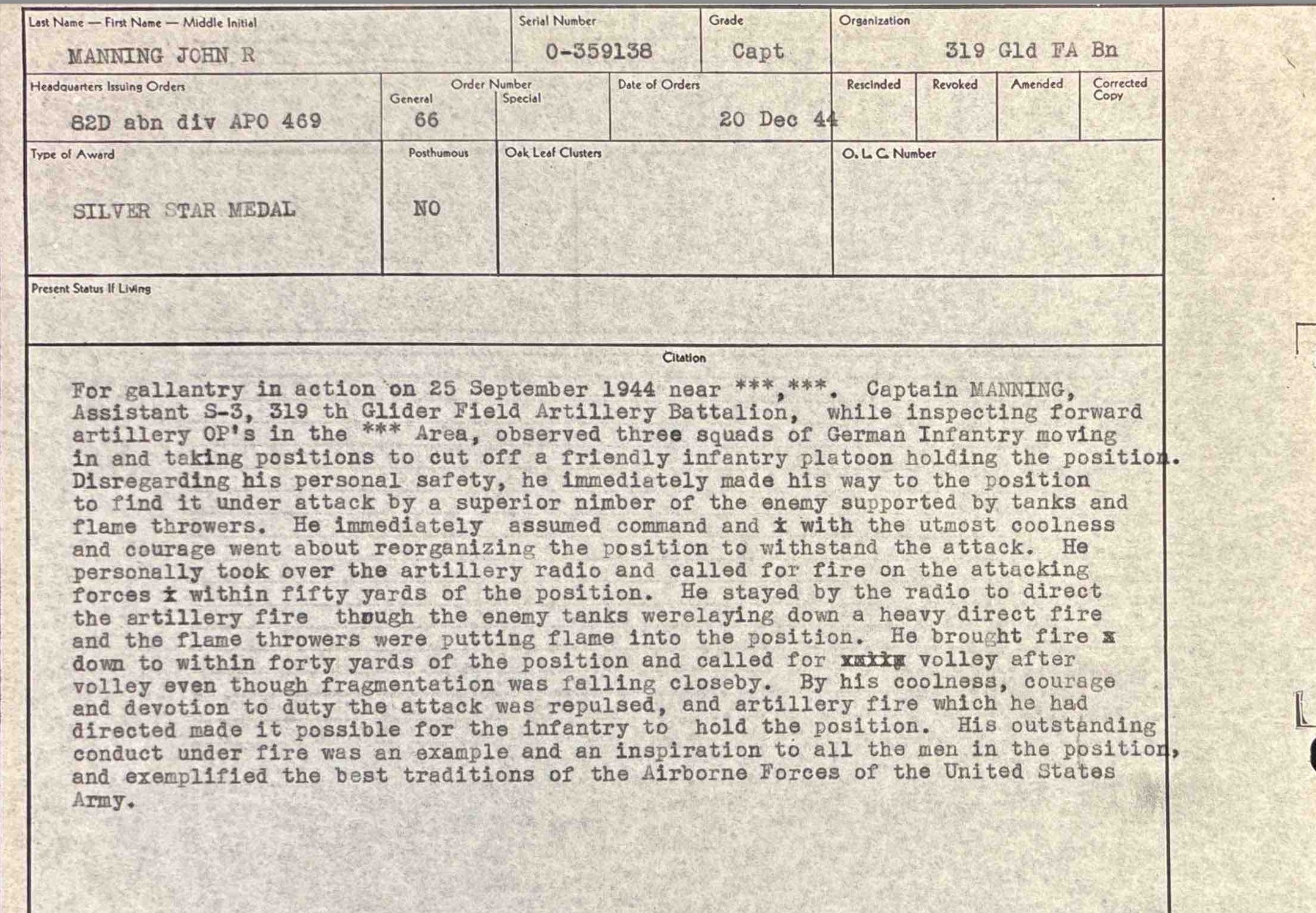

We blew up two flame throwers and a few tanks

We were immediately involved in supporting the capture of Nijmegen and its bridge over the Waal River. This operation was a strenuous one for the paratroopers and other infantry we supported. We did not get much close contact with enemy ourselves. However, before the crossing had been secured we were assigned to support the 325th, which was holding the southeastern border of our encircled sector. They were near the town of Mook and were receiving pressure. Sartain went with me to check out the situation as I had assigned one of his Lieutenants as a forward observer there. The troops were quite uneasy and the attackers had tanks and flame throwers. I discussed the situation with Sartain and was ready to give them a pep talk and leave - but he thought we should stay and work with them a while. The situation deteriorated quickly, as they brought in more equipment against us. I took over directing the artillery. It got down to me talking directly to Battery "B" (Andrew Hawkins Battery) and his section chief Sgt Deloss Richardson, who had been my First Sergeant in Battery "C". Del and I coordinated things down to the last mil of elevation and the last yard of distance. We were able to drop the artillery rounds on the attackers within 25 or 30 yards of where we sat. We blew up two flame throwers, a few tanks, and caused a good amount of damage and confusion. Finally got things cooled off. Evidently the Germans were impressed enough to take their attack somewhere else.

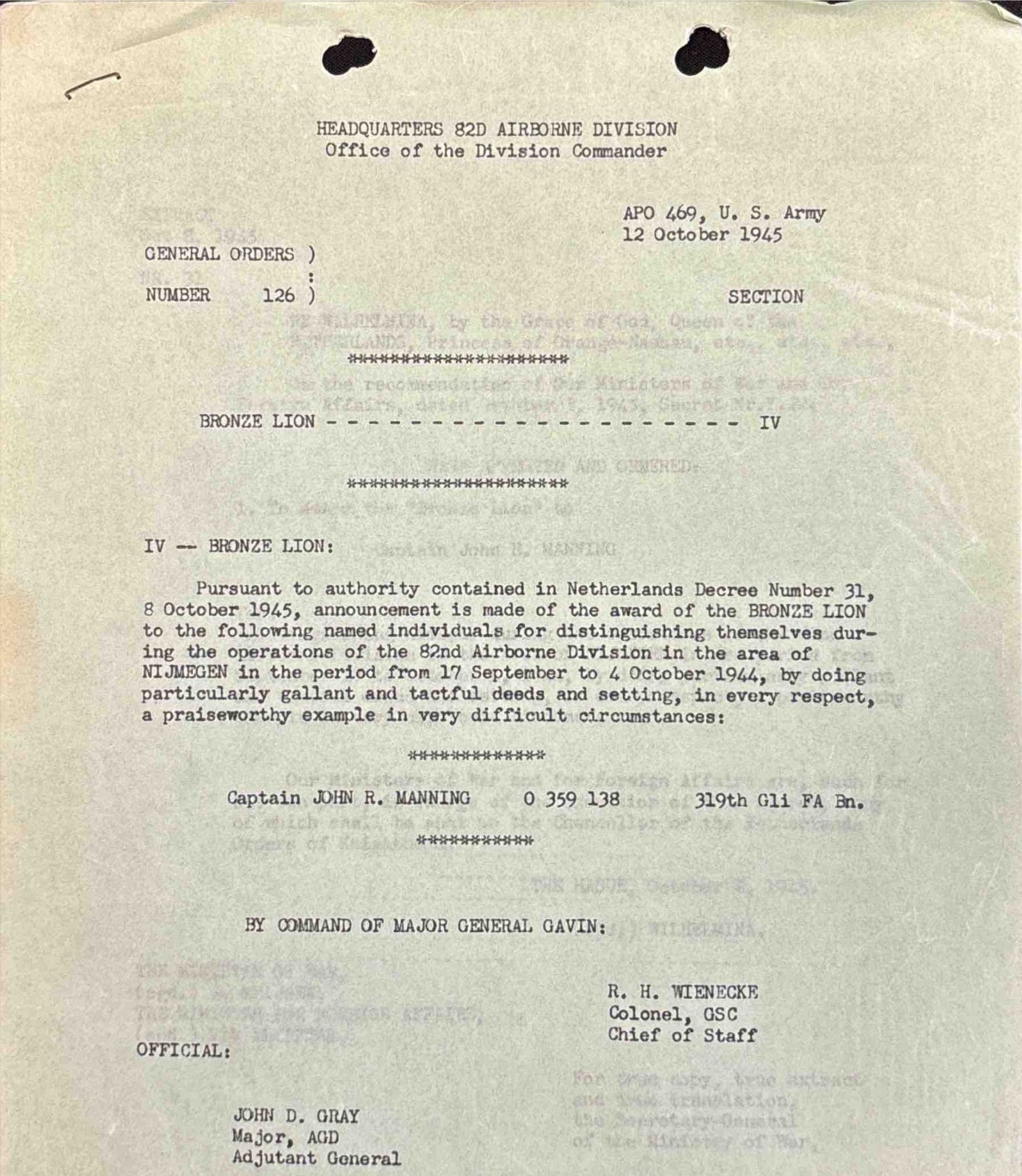

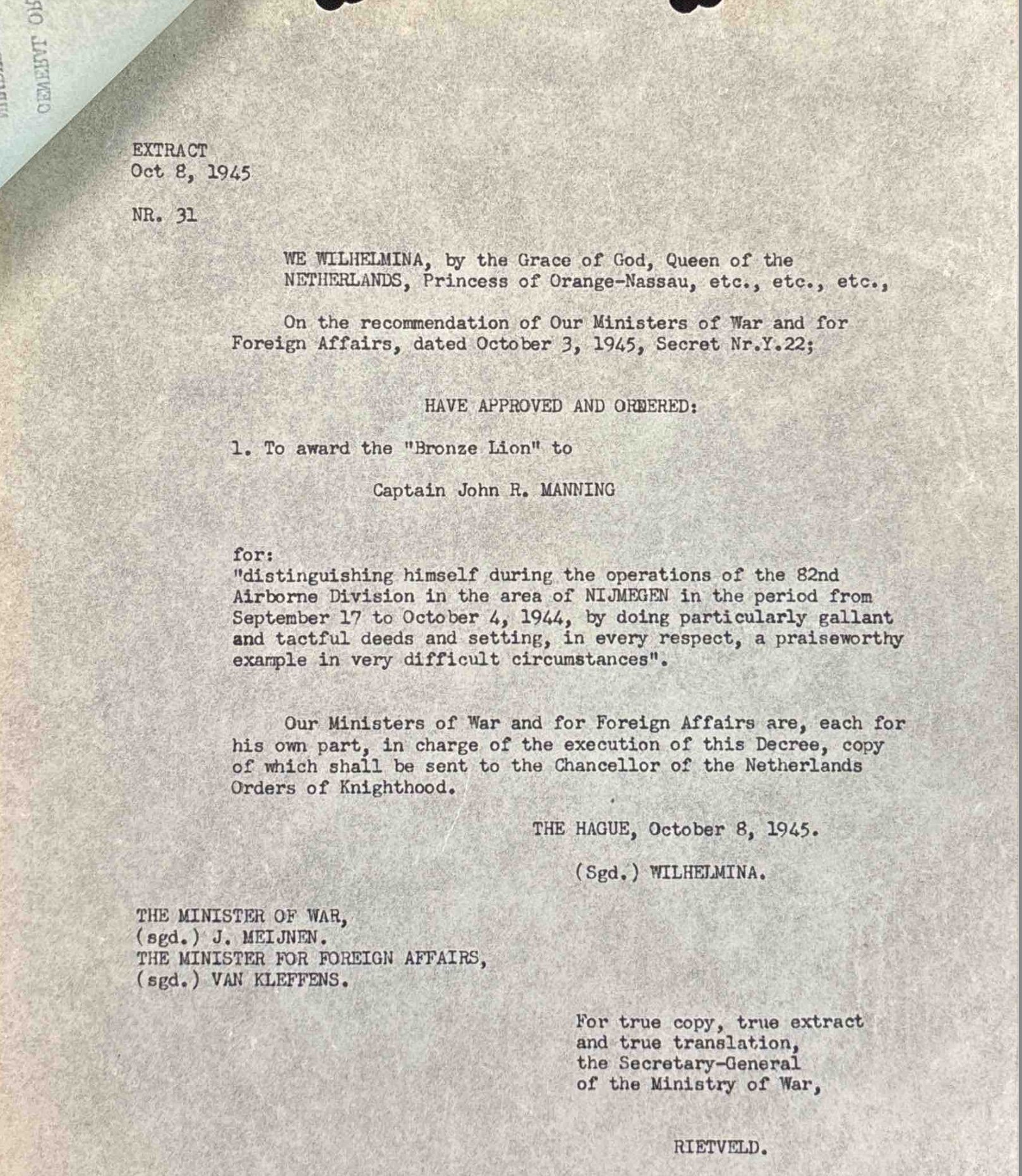

Evidently this action was a more important part of the scheme of things than I imagined. I was awarded the Silver Star and the Order of the Bronze Lion by the Netherlands government. Sartain was also the recipient of decorations.

"The only hill in Holland"

Shortly after, we were alerted to move over the Waal Bridge and go into place to support the Arnhem assault. On the north side of the river we were in flat farmland and cabbage patches. Where we had landed on the south side we had been on "the only hill in Holland" complete with some heavily treed areas. The new location improved the range and breadth of fire for our batteries but left them more exposed. It also cut back on the positions for artillery observation posts. We were given two pilots and two Piper Cub planes to use for observation. One capable pilot and one not so capable. Most of the time, I was able to get Morgan, the capable one. In the book "A Bridge too Far," which was written about this campaign, they mention the artillery support of one operation involving the silencing of a German 88. It was unsuccessful because the artillery response was too slow. I'll always believe it was I and the not so capable pilot who flubbed.

We had been told of the specific objective and had located it on the map. Once in the air we were the recipients of quite a bit of enemy attention. The pilot began to get panicky and I was having a hard time adjusting the rounds. He suddenly put us into a spin, and when we came out close to the ground he said we had plane trouble and must head in. The gun did not get silenced that day. Miller told me later that he was going to insist that they equip him with a chute - if he had had one he would have used it. I wonder what he thought I was going to do without a pilot!

"There is a German gunner calculating the range to the bridge right now”

As history records, the Arnhem crossing was never secured even after a long and bloody battle. We continued in support for some time and were finally ordered to retire through some regular army troops which were coming up from the rear. One incident I will always remember. The army brass was very conscious of the cooperation and loyalty of the Dutch people and they wanted all the baggage of the men checked for illegal "souvenirs." In the DivArty group it was decided to have a staff officer from one battalion check out the troops of an adjacent battalion. I got the job of checking the 320th - who were already across the bridge and south of Nijmegen. When I had finished the checking, I headed back across the bridge. The driver I had was an American Indian by the name of Janus. We had developed a bit of rapport and as we approached the bridge I was kidding him "there is a German gunner calculating the range to the bridge right now and the shot will be on the way by the time we get on it." He offered to bet me and we started across the bridge. “The Brits” had been with the incoming troops and had posted signs on the bridge - "Get Mobile" (in plain English, Keep Moving). We had just come up on one of those signs when the first round hit. I really think Janus's foot went through the floor boards - that Jeep took off! Immediately at the far end of the bridge we passed the 319th in column headed for the crossing - everyone hitting the ditch. We had obeyed the "Get Mobile" sign.

We were assigned to the Rheims area of France at a French army post near Chalons-sur-Marne. Our battalion received Division commendation for the roles we had played in the Holland operation. Even then, though, it seemed such a waste of lives, time, and money. In my opinion, General Montgomery's self aggrandizement got the best of Eisenhower and we were committed to a cause which was unsupportable.

He was a good pilot and one who loved to be flashy

In this location we did little training beyond hikes and physical workouts, at first. As the "utility" staff officer, I was assigned the job of finding a location for an officer’s club-party house. It was suggested that I investigate in Chalons-sur-Marne. Having become quite accustomed to traveling by Piper Cub, I enlisted Morgan to transport me. He was a good pilot, and one who loved to be flashy. Various times on the road to Chalons he would drop down and run along on the Highway for a few yards - just to excite the populace. When we got to Chalons it turned out to be a moderate sized town with a large central square. That square took Morgans eye - we dive-bombed it at least 15 times. We had nothing to drop - just diving in as close to the ground as possible and roaring back up and out. We did attract a lot of attention! After he got tired of that, he found a small pasture at the edge of the town and landed. We did not have to worry about transportation - the Gendarme were there! After a stint in the local police office we were allowed to leave - and also given the address of a house available for the officers to rent. I think Colonel Todd had to clear this caper with General March of DivArty and he remembered it - to the point of having me appointed as Provost Marshal of Chalons while our troops were in the area. It always seemed that some lady in the town would show up to help us enjoy the neighborhood. In Chalons, it was Yvonne Dettling, the assistant librarian. She helped the Colonel arrange for dances and other outings.

We saw our first "buzz-bombs"

Army regulations required that Airborne troops being held in reserve must participate in some aerial exercise at least every few weeks. I inherited the assignment at the nearest airport of running the men through these mandatory Glider rides. A barracks was set up; the troops were rotated in, given so many hours of air time, and then returned to their posts. Right in the midst of this operation the Germans precipitated the Bulge. General Ridgeway was our Corps commander and the orders came down to close up the training operations and be on the road in two days! It is hard to believe we did it. We went through the Bastogne area before the Germans reached it and we became the northern front at Goronne.

We were pushed back some from Goronne but most of our contact was by artillery - ours going out, theirs coming in. After the hold-out at Bastogne we were able to straighten out the front and were ordered to proceed through Liechtenstein towards the German border. During this march we saw our first "buzz-bombs." They were about half again as big as a piper cub and more compact. They trundled along overhead at a low altitude but we were told not to try to shoot them down. It seemed wrong to let these things go on to their target in England, but we understood that sometimes they were intercepted over the Channel.

We soon were closely attached to some of the Paratroopers operating as ground infantry and headed for the German border. It was cold and snowy winter weather and a continual problem to keep our Jeep moving cross country. We finally caught up with some Germans at a border point and were able to provide some active support. I got a call from the Battalion HQ to report to the Colonel. He told me that they were passing our TD's (Temporary Duty) assignments back to the states and that the Battalion had been granted one. It was the consensus at the HQ that it be given to me! A quick end to my combat experience.

"Sorry, Captain, they tried to escape and we had to shoot them"

The Division had a rear echelon office at Malmedy to which I was ordered to report. The square in this town was the scene of a mass killing of American prisoners by the Germans about 6 months before. It brought to mind that war brings out the worst in all of us. Shortly before my last assignment, while I was traveling with the Paratroopers, we captured six German prisoners. The Captain of the Paratroopers interrogated them and then assigned two men to escort them to the rear. The two escorters’ were back with us within a half hour - "Sorry, Captain, they tried to escape and we had to shoot them"

Home and love at last!

From Malmedy, Belgium, I was given transportation to Le Havre, France and passage on a Victory ship bound for New York. Starting with my field assignment, and from the rear echelon post, I had gradually collected my various duffel bags and other paraphernalia. By the time I unloaded in New York I found it necessary to carry some bags some distance - put them down - go back for the rest portage them on ahead - go back - etc. Finally got on the Erie train at Hoboken for the ride home. Still the main line then, it seemed so tranquil and welcoming to ride up through Tuxedo, Monroe, Chester, and Goshen. Finally arrived in Middletown to find that the station was no longer in use and I was dropped off in the middle of the rail yard. Marg was there - I had been able to call her from New York before I got on the train. Home and love at last!

As I write these lines the television is reporting the ground war starting in the Persian Gulf. This conflict has been almost like a TV program. There has been a lot of communication to and from the troops. At the time I was overseas Marg and I communicated by "V" Mail - letters which were reduced to filmed copies about the size of a post card. We still have some of them around the house. Letters meant a lot to both of us - although they did not move super efficiently.

In the combat theater one is distracted by the novelty of ones surroundings or the enemy. The letters from home seem like windows to an unknown world. I know the letters I received from Marg, and from my mother, were what kept me sane.

STL Archive

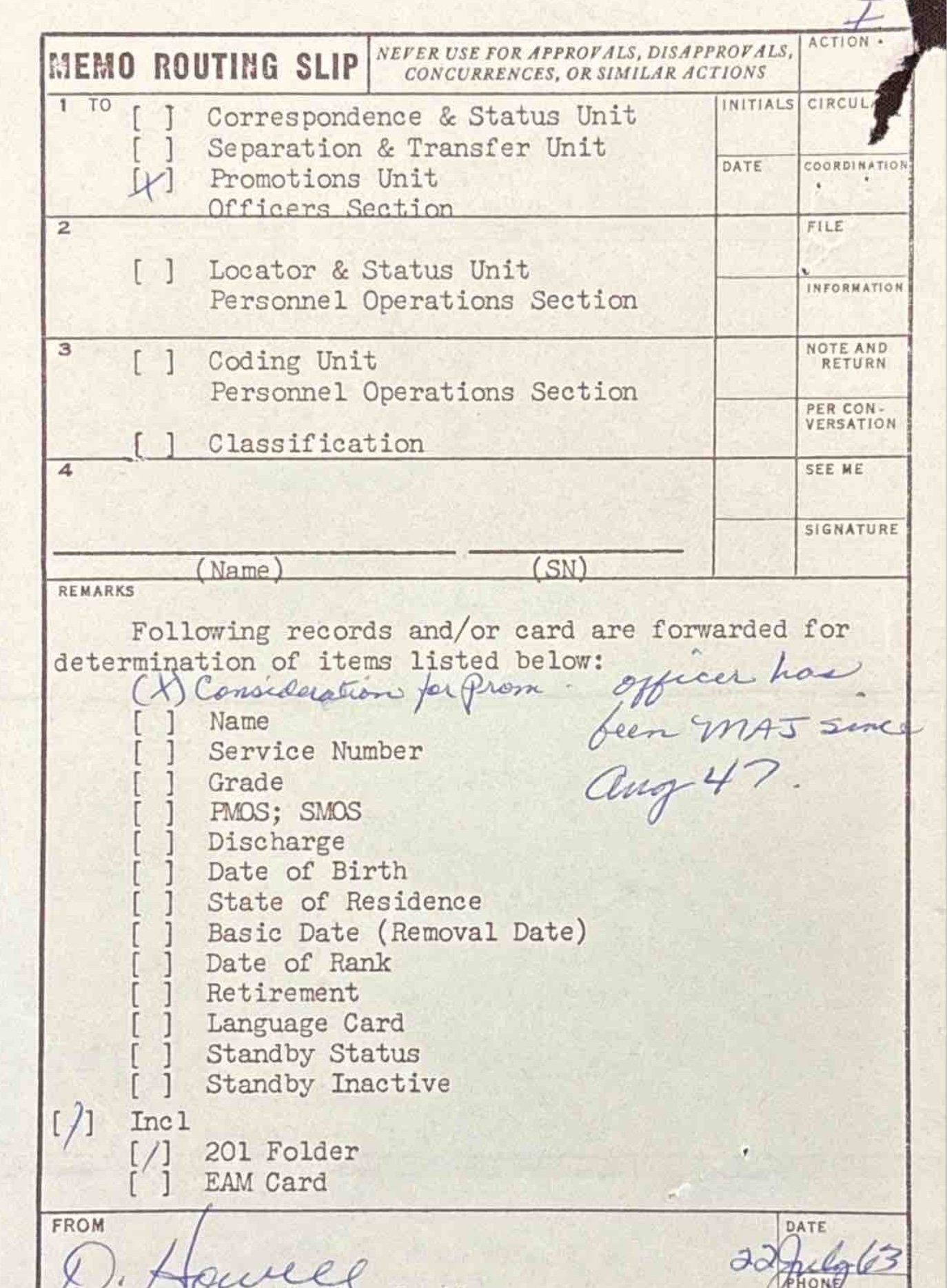

Following written (unedited for now) by Joe Covais

May 23, 2023

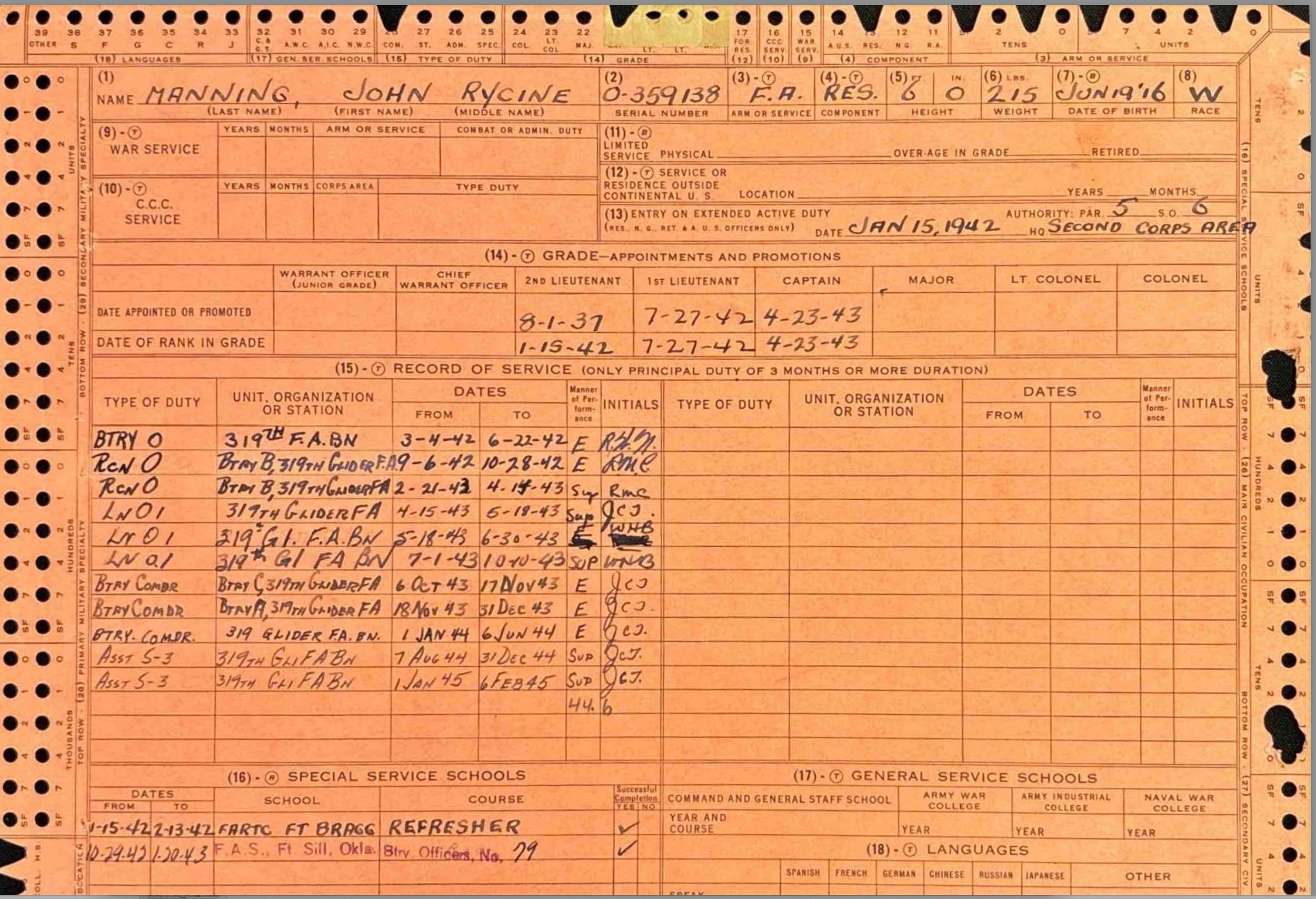

Soldier Name: John Racine Manning

ASN: 0-359138

Rank at date of discharge: major - July 12, 1945

DOB: June 19, 1916, Middletown, New York

DOD: October 22, 2004, near Howey-in-the-Hills, Florida.

Early Life:

John R. Manning was the son of Hiram and Emma Manning. He grew up in Unionville, NY, in the Hudson river valley, where his family owned a dry-goods and agricultural supplies store. He graduated high school in 1934 and went on to enroll at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY,

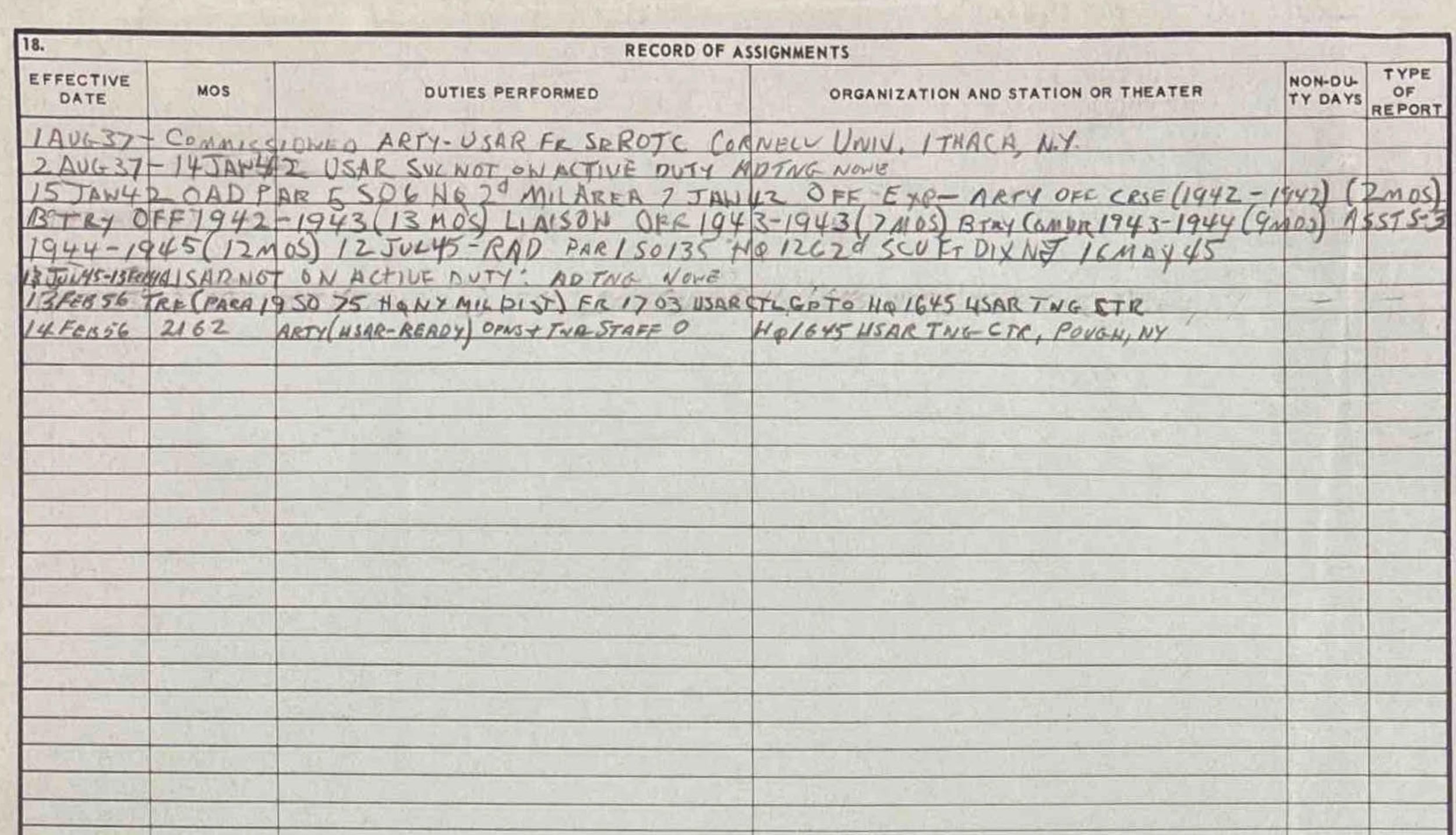

Prior military service:

As a student at Cornell, Manning was enrolled in the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC). In those days, participation in the ROTC was compulsory for male students during their first 2 years of college. Manning graduated from Cornell in 1938 with a Bachelor's of Science in Agriculture.

Service in the US Army:

John Manning was inducted into active service on January 14th, 1942. He received basic training at Ft. Bragg, NC. A group photograph taken in May, 1942, of the HQ Battery, of what was then the 319th Field Artillery Bn., at Camp Claibourne, LA, shows Manning as a 2nd Lt. posed among the officer cadre’.

Manning was placed as officer in charge of the battalion’s motor-pool. “I never realized that so many men did not know the basics of driving a car, much less a 2 1/2-ton truck,” he wrote decades later. “I rode on more running boards, and listened to more gear grinding than anyone person should have to do in a life time.”

Nonetheless, Manning enjoyed working with the enlisted men. He also showed a clear ability to relate to and motivate those under his direct supervision. Capt. Charles L. Sartain, who came to know Manning as well as anyone in the unit, described Manning’s manner in these terms, “Johnny Manning never cared much for military formalities, never talked down to people. He treated everyone like a human-being and the men liked that, they really did.”

Since the outfit’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Harry Bertsch, believed the battalion should have a jazz band, he volunteered Manning to put one together. No funds were allotted for such an ancillary feature in the unit, so Manning had to scrounge instruments from what he described as, “unlikely places.” Apparently the thrown together band met with some success. “Our most popular tunes were the tiger Rag and Beer Barrel Polka.”

Service with the 319th GFAB:

In the spring of 1942, the 82d division was converted to an airborne division. Manning, who stood 6’1” tall and weighed 220 pounds, was too large for training as a paratrooper. Consequently he remained with the 319th Field Artillery – now re-designated as a glider unit. the division was transferred from Camp Claiborne to Ft. Bragg, NC, where its training with gliders began and continued until the unit was sent overseas.

Manning’s memory of the trip, aside from the overcrowded conditions, also included nights spent on the stern of the ship. With all lights blacked-out, the view of the stars was unlike anything he’d ever seen. Under the tutelage of one of the battalion surgeons, Manning learned to recognize the constellations of the night sky.

That journey took him across the Atlantic to French Morocco and soon a harrowing glider mission over the Atlas mountains to Algeria. The flight was made amidst a driving sand-storm. “One hasn't lived until one rides in a flimsy pipe and canvas glider staring out at a rope which disappears into a black cloud and seems to have a life of its own,” Manning later recalled.

Promoted now to 1st Lt., Manning was next assigned as executive officer of “B” Battery. Night marches were intended to develop the men’s ability to find their way through strange territory without a map. On such occasions, Manning’s newly acquired familiarity with the constellations were a significant aid in finding the battery’s way back to camp.

In July of 1943, the 319th was reorganized from having two firing batteries – each with six guns, to three batteries of four-guns. Popular with the men, Manning had shown himself to be a competent and resourceful officer, worthy of greater responsibility. He was promoted to Captain - and placed in charge of the new “C” Battery, With then Lt. Sartain as his executive officer.

Manning and Sartain held a mutual command philosophy – one based on respect coupled with high expectations. If other officers saw the reorganization as an opportunity to purge their ranks of misfits or eccentrics, Manning and Sartain saw it as an opportunity to put their shared command strategy to the test.

“Charlie and I took it as a challenge and worked hard at developing an esprit de corps in our battery,” he later wrote. “Many of the men were odd-balls in many ways, but they were tough and could work. In the long run we were quite successful.” Corporal Bob Storms described part of Manning’s style of command when he said, “That Captain Manning was good with us. He was the only one I ever knowed that every once in a while he’d have a bull session. If some officers were picking on you or you were getting extra duty for some reason or another you could raise your hand. When it came your turn you got up there and he wanted to know what your gripe was. So you told him, like a lieutenant put you on duty a couple of times too quick instead of going by the roster. He’d say, that’s your bitch? I’d say, yep, that’s it. He’d tell you, sit down. Then he’d ask the Lieutenant how come? Well, I told him to do this or that and he took his time, so I give him extra duty. He says, when you give anybody extra duty you check with me, that’s my job. Your job is to go by the roster. He’s the only officer I ever knowed do that. Yup, he was some Captain.”

Italy:

As it turned out, the unit’s baptism of fire came in September as part of Operation Avalanche, the invasion of the Italian mainland. Ironically, for the glider artillerymen, it was an amphibious, not an airborne operation, directed at Maiori, a little village with a ring of mountains surrounding it. The principal mission for the battalion was to interrupt the movement of German supplies and reinforcements from Naples in the north, south to the allied beachhead at Salerno.

The battalion’s batteries, “C” among them, were set up on the back side of these mountains, placed within a vineyard. The terrain was so mountainous that the 319th gunners were unable to elevate their howitzers sufficiently. To compensate, trenches for the trails of the howitzers were dug in order to achieve an angle of fire which was nearly vertical.

Manning later described the position on the mountain top from which he and other officers directed the fire. “We took turns at the OP - keeping in shape climbing up and down the trail,” he wrote. “. "C" Battery got a large number of the firing assignments as our odd-ball battery location turned out to be the most advantageous relative to the target areas. One of the problems we tried to solve was being able to hit the target areas on the forward slope. We got so we could actually see the projectiles sail over our heads, we were so high above the battery location. The 105's had 7 powder bags in each shell, and Sartain came up with the thought that we might be able to drop the rounds closer to the ridge by removing some of the powder. The bags were of different sizes, so we had lots of possibilities to work with. We were successful to some extent.”

Manning and Sartain took turns directing fire from the mountaintops for the following few weeks. As the Allied presence increased, other forces brought their power to bare – including the British Navy.

“One interesting experience was my contact with a British Naval gunnery officer,” Manning remembered. “He had been sent to act as an observer for one of their large warships in Salerno Bay. He and I worked out patterns of targets and he took over on the ones we could not nullify. It was very impressive to hear those big rounds come whistling in. He gave me his issue winter coat when he returned to ship. It served me very well through the war and afterwards.”

Following the breakout from Salerno, the 319th entered Naples. It is said that personnel of “C” Battery were among the first to enter the city. A photograph believed taken by photographer Frank Cappa, of American troops entering Naples, on close examination, shows members of the 319th. The leading jeep, driven by Manning’s driver, Louis Sosa, shows Captain manning seated in the passenger seat. The soldier in the back of the jeep appears to be Corporal Ted Covais.

Further action along the Volturno River followed. Ed Ryan was one radioman who was often working under Manning, sending his fire commands.

Ryan remembered one incident, saying, “In Italy he got hold of a radio from the front deck of a tank and was calling artillery fire from it. I said to him later that that was a pretty dangerous thing to do. His answer was, You got to get this over with.”

after this action, Manning’s battery, along with the rest of the 319th was part of the city’s occupation force.

Ireland and England:

In November the 319th left Naples and relocated to Northern Ireland. 1943 came to an end with the battalion quartered in Quonset huts near the town of Ballymena. Daylight was so short as to allow for only limited training, mostly marches to keep the men in condition. Actual practice with the guns was difficult because of the restrictions place on military operations by the local authorities.

In February of 1944 the 319th was moved to a 17th Century manor house located just outside the town of Lubenham, a hamlet near Market Harborough, England. At the end of that month the arrangement of three fire batteries was discontinued. The battalion returned to its previous configuration of two firing batteries and one Headquarters battery. The men from “C” Battery were returned for their former batteries, but the duo of Captain Manning and Lt. Sartain as his executive officer had proven so effective they were placed in charge of “A” Battery.

“Manning was, how shall I say it, a formative influence in my military career,” commented Captain Sartain decades later. “Manning was low key and all you had to do was just be around him and watch how he worked. Johnny Manning knew what he was doing, knew what his aims were without proselytizing anybody or without advertising it. He was just a good guy.”

Normandy – Operation Neptune:

The 319th glided into Normandy late on the evening of June 6th, 1944. “It was almost dusk as we flew over the White Cliffs of Dover,” Manning wrote years later. “ At any other time it would have been very scenic. Our only concern was for our survival to become part of the operation after landing. As we arrived over the French countryside we received quite a bit of flak and machine gun fire. The pilot of the tow plane was getting very uncomfortable. He told us to cut loose, or he would cut us loose at his end of the tow line. We complied quickly in order to preserve what maneuverability we could. The pilot and co-pilot asked me to take one of their watches and stand between them to count down the seconds for our glide in. These gliders land at 90 miles per hour with the brakes fully locked - and just run it out. We picked the largest field we could identify in our range of possibilities - hit it near dead center and were on a dead run for a row of big trees. We must have hit between two trunks. I came to on a pile of rubble still holding the watch. The pilot was hung up in one tree; the co-pilot was dead on the ground. I found my right hand to be cradling my partially disconnected thumb. Naturally, I bypassed my medical packet and wrapped the thumb in a dirty handkerchief. I dragged out my 45 Colt and tried to take charge. The enemy soldiers near us appeared to be confused and scared, so it was possible to assess our situation. I found that I could hardly move my back. We found ourselves near a farm lane which appeared to lead in the compass direction of St. Mere Eglise (our focus point) so we proceeded down it. I set up a command post and we gradually rounded up about half of our battery. By afternoon I was able to get my group to St. Mere Eglise and check in with Battalion. They decided that my right hand was useless and I should head out the medic evacuation route. Sartain took over the battery.”

As popular as Captain Manning was, his injury and evacuation only amplified his status in the 319th. “They had a hell of a time with him,” Recalled Sergeant Robert Rappi. “He wanted to stay with the outfit. The story was it took six men to put him aboard the boat.”

Returned back to England with other casualties, Manning was hospitalized for nearly a month. During recovery, his greatest fear was that he would be sent to a replacement depot and separated from the 319th. Having heard the unit had returned to Lubenham, Manning secreted himself out of the hospital and made his way back to the unit on his own.

Since Manning was still healing and didn’t have full use of his right hand, he was reassigned from his position as “A” Battery commander to serve as the battalion S-3 – essentially a liaison between the unit and the infantry it would be supporting in combat.

Holland – Operation market Garden:

On September 18th, 1944, the 319th participated in the invasion of Holland. Open terrain, a daylight landing, and smaller, more maneuverable gliders, all combined to make the Holland landings much less chaotic than those in Normandy had been.

During the time the battalion spent participating in Market-Garden, its position, though shifted several times, remained in the vicinity of Nijmegen, generally in support of the 508th parachute and 325th Glider Infantry regiments. The objectives were ambitious – nothing less than an enormous maneuver around the German Army’s northern flank. Had the operation gone as planned it could have brought the war to a swift close, but two months of bitter fighting resulted in a muddy stalemate.

Throughout, Captain Manning operated as the 319th liaison officer, coordinating support of the infantry. One episode in particular exemplifies Manning’s qualities of command and character. On September 25th the battalion was supporting troops of the 325th Glider Infantry in position near the town of Mook, when reports came in of a strong, aggressive German probe.

Manning described what happened: “Sartain went with me to check out the situation as I had assigned one of his Lieutenants as a forward observer there. The troops were quite uneasy and the attackers had tanks and flame throwers. I discussed the situation with Sartain and was ready to give them a pep talk and leave - but he thought we should stay and work with them a while. The situation deteriorated quickly, as they brought in more equipment against us. I took over directing the artillery. It got down to me talking directly to Battery "B" (Andrew Johnstons Battery) and his section chief Sgt Deloss Richardson, who had been my First Sergeant in Battery "C". Del and I 'coordinated things down to the last mil of elevation and the last yard of distance. We were able to drop the artillery rounds on the attackers within 25 or 30 yards of where we sat. We blew up two flame throwers, a few tanks, and caused a good amount of damage and confusion. Finally got things cooled off. Evidently the Germans were impressed enough to take their attack somewhere else.

Sartain remembered the action as the most skilled demonstration of artillery direction he saw during the war. “If it hadn’t been for Manning on that artillery we never would have survived,” he later said. “Manning had that whole battlefield zeroed in on concentration points. All he had to do was call for concentration point 11, or concentration point 7, or whatever, and man the battery came in.

Manning received the silver Star for his actions that day. The citation read: “For gallantry in action, 25th September, 1944, near Holland The battalion assistant S3 on routine inspection tour of forward artillery Ops in the area observed three squads of German infantry moving in and taking positions to cut off a friendly infantry platoon holding the position. He immediately made his way to the infantry position through heavy small arms fire, and found the position under attack by a superior number of the enemy, supported by tanks and flamethrowers. The battalion S3 assumed command, while Captain Sartain, with the utmost coolness and courage, went about reorganizing the position, passing among the men time after time, giving encouragement and instruction to each individual soldier. His courage and devotion to duty, in utter disregard of his personal safety, was a great factor in halting the attack and holding the position until the arrival of reinforcements and resupply of ammunition. His courage, coolness, and conduct under fire was an example and inspiration to all the men in the position, and exemplified the best traditions of the service.”

The Bulge

The Ardennes, or “Battle of the Bulge,” as it is popularly known, may have been the most trying of the 319’s campaigns. In reality, it was two battles fought simultaneously: one against the German army, in this case often fanatical, aggressive SS formations, and the other against unrelenting winter weather. While the former posed the more obvious and immediately deadly foe, the toll which fighting in winter took was, in fact, greater than battle casualties.

The Bulge campaign dragged on through January and into February of 1945. The 319th remained in more or less continuous contact with the enemy – first blunting the German attack with defensive fire missions which shattered their armor and supporting infantry, then reorienting its fire to augment the Allied counteroffensive.

By early March the battalion was on the German border. It was becoming clear to everyone that German resistance was crumbling. With the end of the war in Europe in sight, the Army was already shifting its focus to the Pacific theater. Deserving men with plenty of combat experience were needed to train a vast invasion force for the anticipated invasion of mainland Japan.

Manning fit the profile. He described what happened: “I got a call from the Battalion HQ to report to the Colonel. He told me that they were passing our TD's (Temporary Duty) assignments back to the states and that the Battalion had been granted one. It was the consensus at the HQ that it be given to me! A quick end to my combat experience.

From Malmedy I was given transportation to LeHarve and passage on a Victory ship bound for New York. Starting with my field assignment, and from the rear echelon post, I had gradually collected my various duffel bags and other paraphernalia. By the time I unloaded in New York I found it necessary to carry some bags some distance - put them down - go back for the rest portage them on ahead - go back - etc. Finally got on the Erie train at Hoboken for the ride home. Still the main line then, it seemed so tranquil and welcoming to ride up through Tuxedo, Monroe, Chester, and Goshen. Finally arrived in Middletown to find that the station was no longer in use and I was. dropped off in the middle of the rail yard. Marg was there - I had been able to call her from New York before I got on the train. Home and love at last!

Now with the rank of Major, Manning would surely have been a part of the anticipated invasion of Japan – except for the abrupt end with which the Atomic bomb ended the conflict.

Post-War Life.

John Manning returned to running his family’s agricultural supply store. As times changed, so did Manning. He became involved with construction of residential and commercial buildings. Later on Manning became a realtor, eventually specializing in real-estate appraisals through New York’s Hudson Valley.

Leadership came naturally for Major Manning. In civilian life he expressed this through his commitment to community service. Manning became involved in and helped charter several civic organizations, was a volunteer fireman, he served as an elder in his Presbyterian church and on several committees. Manning was active in the Kiwanis, served on the local school board, and town planning board as well.

Though it was not until his later years that his interest in veteran’s organizations grew, Manning and Sartain maintained an active friendship throughout their lives, with occasional visits to each other’s homes.

He served as a volunteer fireman for the Johnson Fire Company. He was a Charter member of the Minisink Kiwanis Club which continues to provide service to the area where he lived. He remained very active in Kiwanis serving as Club President and later as Area Lieutenant Governor. He was also a past member of Lions Club in Middletown. John served as the president of the school board for the Minisink Valley Central School. He also served as the Planning Board Chairman for the Town of Minisink. Memorial Services will be held on

“A mass of organized confusion. One’s dependence is heavily on oneself, even though your comrades in arms are supporting you as you are supporting them - be it in hand-to-hand combat, or in supporting artillery fire. Death and injuries become almost mundane. One cannot help but feel deep sympathy for the civilians 'whose lives are on the line, and whose properties are being destroyed. I found that I survived by concentrating on each immediate problem - how to get to the next corner, or map location; making a schedule to get us through the next few hours; trying to secure our position through the night. As each problem was solved, or changed, we could measure our progress to the next plateau. We found, as we went through the various campaigns, which this attitude served us well - in moving forward, or in retreat. There is no time to worry about one’s own mortality, or about the progress in the "big picture". One has to develop confidence in himself and in his immediate group - then, after one step at a time, the end, of any given operation, suddenly arrives.”

“Keep your head down but keep going and it’s gonna work out. “