Andrew J. Hawkins, Jr

ASN:0-415323

ANDREW JOHNSTON HAWKINS - A PERSONAL HISTORY OF WORLD WAR II

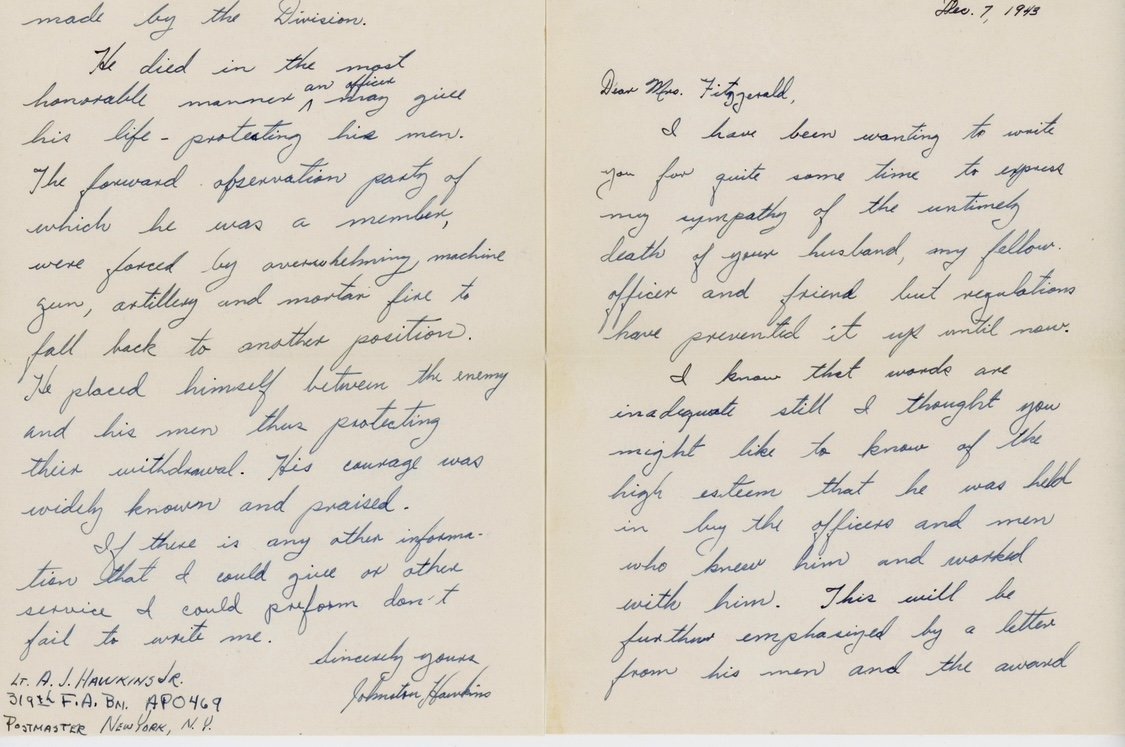

As I sat in the bucket seat of the old C47 droning over the English Channel, I looked up and down the faces of the other seventeen men facing one another. All were dressed in full battle regalia, some with blackened faces, all with every conceivable type of military contraption strapped to their harnesses. Of these men, I knew only one, Sergeant Sample, my signal sergeant. He was sitting at the other end of the plane. It was June 6, 1944, a little after midnight. I held the rank of Captain and was Artillery Liaison Officer for the 319th Glider Field Artillery Battalion to the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division. The other men on the plane with me were all specialists, some demolition men, parachute maintenance men, interpreters, and military intelligence.

Click here for Video interview with Andrew Hawkins Part 1

As I sat there, I began to think back to how in the heck I ever got in this position, a very vulnerable one. I was born and raised in Birmingham, Alabama and had gone to college at Alabama Polytechnic Institute in Auburn, Alabama (now called Auburn University). (ed. note: Captain Hawkins had just celebrated his 25th birthday May 24, 1944.) I graduated in June 1941, with a Bachelor of Science in chemical engineering. Among other things, I had taken military training, ROTC, all through college and had received a Second Lieutenant commission in the Field Artillery Reserve. Although many of my classmates had gone into active duty upon graduation, I went to work for the DuPont Company in Wilmington, Delaware. I worked in the rubber laboratory until shortly after Pearl Harbor, when I was called into active military service. My service began on January 1, 1942.

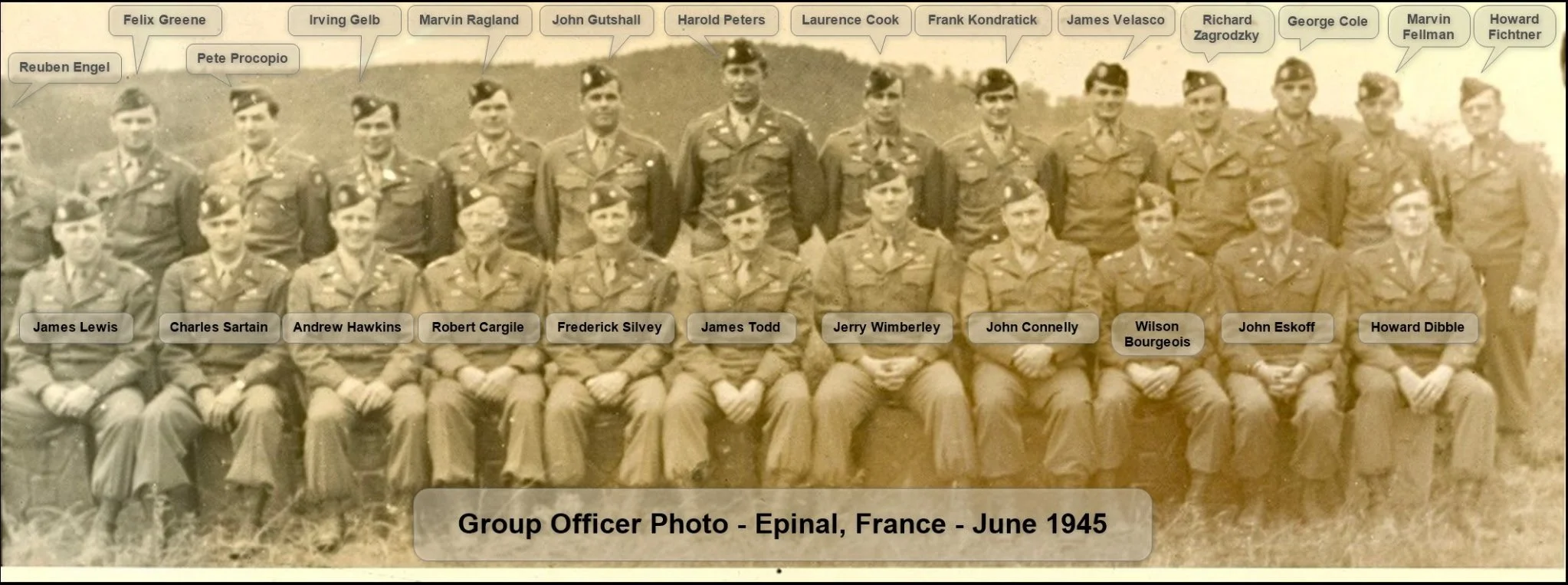

I went first to Fort Bragg, North Carolina for a few months of training and then, in early April 1942, became part of the original officers and men who activated the 82nd Infantry Division. We trained in Camp Claiborne Louisiana. In the Fall of that year, after special exercises, we were proclaimed the leading division of the five newly activated Army divisions in the United States. We were given the honor of being the men who were to be used to form two American Airborne Divisions, the 82nd Airborne Division and the 101st Airborne Division. Major General Omar Bradley was our Division Commander, Brigadier General Matthew Ridgeway, our Assistant Division Commander, and Colonel Maxwell Taylor our Chief of Staff. All these men later became Chiefs of Staff of the United States Army and men with important political and military significance. It was their leadership that caused our divisions to be what eventually turned out among the top fighting units of the United States Army during World War II.

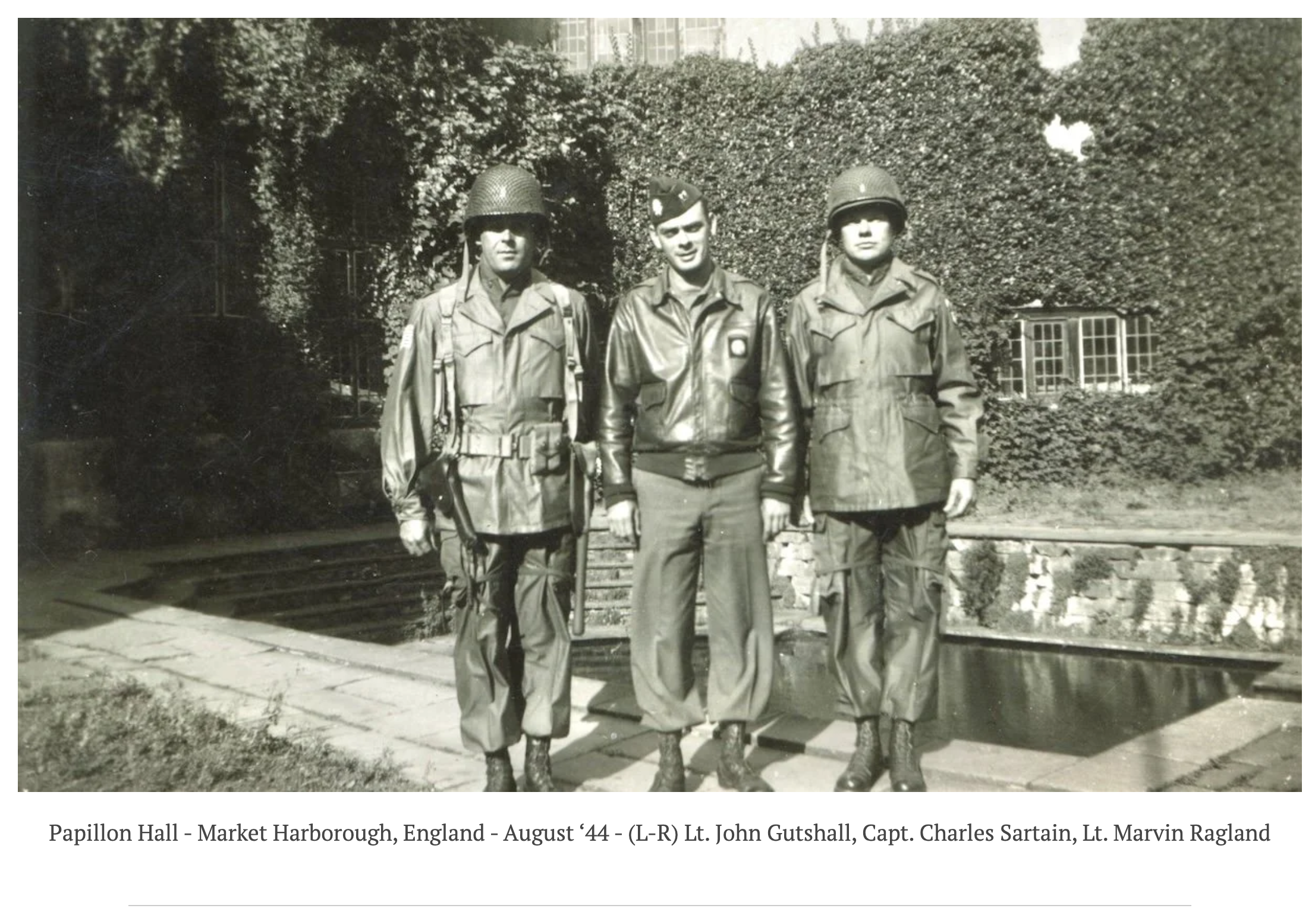

When we were designated as the nucleus of the Airborne Units, everyone was given a choice as to whether he wanted to go to parachute school or be trained as glider troops. At this time, I wanted no part of the jumping out of an airplane with a parachute and so I chose to stay with the glider troopers. We trained in Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, and then later moved to Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Later I went to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for special artillery training in the winter of 1942 / 1943.

In May 1943, we were put aboard ships and sent to Casablanca, North Africa. We arrived after having several narrow escapes from submarine warfare in the crossing. Fighting had just ceased in North Africa. We crossed the hot deserts by train and trained in Kairouan and later in Bizerte. Our division led the way in the invasion of Sicily. I was scheduled to go on the second day with my battalion by glider. However, the night before we were to go in, our own Navy shot down many of our own planes which were carrying paratroopers. As a result of depleted air lift capabilities, we did not see action in Sicily. Our training was then intensified as we began to prepare for the invasion of Italy.

One night in September of 1943 we were rushed aboard an LST (Landing Ship Tank). On this ship there was our one artillery battalion, four armored tanks, two bulldozers, and sundry, other military personnel, and equipment. Together with us on two LCI’s (Landing Craft Infantry), we set out on a supersecret mission as a task force of these three unprotected and relatively unarmed vessels. In the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, we were told that we had been chosen as part of a military envelopment of Rome, Italy. According to this plan, the 82nd parachute and glider people were to drop into the outskirts of Rome. Our special group was to go up the Tiber River and bring in the tanks and artillery. Fortunately, though General Maxwell Taylor went into Rome secretly to receive the surrender of Italy to the Allied Forces. When he was there, he saw that Rome was completely encircled by a German armored corps. He immediately sent a specially prepared message that our mission would be suicidal and that we were to be diverted. We were then sent to Salerno Bay to be a part of the seaborne invasion of Italy below Naples.

Our unit in the LST was assigned to the American Rangers. If there was any group rougher than the paratroopers, these were the ones. We landed on the beach two days after the invasion had begun and were rushed up winding roads into the mountains above Maiori, near the Amalfi Coast. We fought there for 28 days in September and October and were later a part of the first group to occupy Naples. We were occupation troops in Naples except for a couple of weeks when we were sent up to the Volturno River just north of Naples as a part of a fight front.

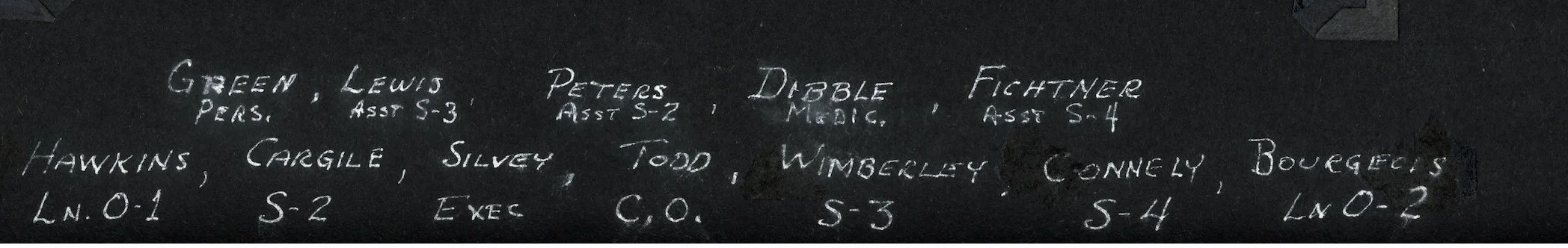

In November of 1943, we again got on Navy transport ships and were taken to Northern Ireland. We trained in Ballyscullion above Belfast until February of 1944 when we were moved to Market Harbor, England.

By this time many units of our division had seen considerable combat. I began to count noses and realized that there were just as many glider troopers getting killed as paratroopers. The paratroopers were receiving extra pay and the glider troopers weren't. I figured that so long as I was taking the same risk, I may as well become a paratrooper and get the extra pay, $100 a month more for a Captain. I went to parachute school which consisted of about five hours of training and three consecutive parachute jumps within one hour of each other. I definitely do not recommend this to anyone.

Since I was one of the few officers in our glider artillery battalion with parachute training, I was assigned the task of liaison officer to the infantry parachute regiment which we would be supporting in the then pending D-day invasion of France. Because of the relative importance of my mission, I was one of the first people in our group to learn of the invasion plans. I helped formulate the plans for our artillery battalion in addition to assisting the infantry regiment.

On June 1, 1944 I moved in with the infantry and stayed with them from then on. We loaded up our planes on June 3 to invade the morning of June 5, however, as history notes, bad weather caused this to be postponed for 24 hours. Although most of our division had seen combat, the 508th Infantry Regiment had not been part of our division up to this time. They were new in Europe and apparently did not know combat. As a result of this, I and my radio operator sergeant were delegated to the last plane in a formation of 72 planes which went into Normandy in one large V, one of many V’s across the channel. So, here I was, just about to become a part of the greatest military invasion in history. I hope that it is never again repeated. It is hard to imagine how it could be with the weapons we have today.

As a result of the unfortunate situation that occurred in Sicily, with the Navy shooting down our own planes full of paratroopers, our planes were routed around the Cotentin Peninsula. The intent was to approach the Drop Zones from the South, avoiding crossing over our Navy ships poised just off the invasion beaches.

The 101st and 82nd Drop Zones were a just few miles inland at strategic points behind the beaches. As we approached the islands of Guernsey and Jersey, we ran into cloud formations and fairly, heavy antiaircraft fire. Despite very strict orders to the troop carrier pilots that no evasive action should be taken, our pilot began to dodge the flak. With this and the clouds, we soon became separated from the remainder of our planes and ultimately wandered to the West since we were the tip end of the left vector of the formation of the 72 planes. The pilot then became lost. The order to stand up and hook up came early, yet the red light remained. I was the number seven man in the jump and the senior officer (Captain) aboard this plane. Antiaircraft fire began to hit our plane heavily and we seemed to be dropping in altitude fast. This turned out to be a very well-fortified area of Normandy. We must have crossed out over the English Channel and then veered further to the West and turned back South. As soon as we got over land again, the green "Go" light was given and we jumped. We were only a couple of hundred yards from the beach. Of course, we had no idea of where we were and I mistook the water I saw, as I dropped to the ground, as that of the flooded lowlands of the Merderet River - where we were supposed to land. The plane was very low when we jumped, probably 300 to 400 feet altitude.

From the time that my parachute opened until I hit the ground, machine gun fire was zipping around me. I landed in a small field about 25 feet from a German machine gun. There were six men who landed in the field behind me. The Germans apparently decided to go out after the group of six soldiers and to pick me off later. I wasted no time in cutting my parachute away with my knife. I ran to the nearest farmhouse and banged on the door to try to get in. Of course, there was a lot of antiaircraft fire, noise, shooting and all types of confusing situations going on all around. I can't blame the Frenchman who came to the door and screamed at me to go away.

He was as frightened as I was. I then ran into a cluster of buildings and climbed up into the loft of a barn. I destroyed all my military codes and any information which, had I been captured, would have been important to the enemy. I also got rid of my gas mask, shovel, and any additional paraphernalia which I knew would not be important to me as I was well aware that we were greatly separated from the remainder of the people with whom I was to have dropped. I climbed down out of the loft after hiding everything that I could in the hay, hoping that some loyal Frenchman would find it. Later they did and I'll tell this story as time progresses.

Somewhat safe for the moment, my conscience began to get the better of me and, inasmuch as I was the senior officer on this plane, I felt it my duty to immediately go back into the fray and try to gather together as many of the men as possible to see if we could start our journey towards where I felt we should be in order to accomplish our missions. Dark and confusing as it was, before long I heard some noise in the brush and after a quick exchange of passwords, I met up with PFC Clifford Ford. We started together to try to find other men. From then on, everything we bumped into was German. There was just no sneaking past them and finally they heard us and opened fire on us. I told Ford to run down the hedgerow, cross over another hedge at the end of the field and then stop and cover me. In the interim, I would fire on the Germans with my pistol and cover his withdrawal. I guess, in his excitement, he forgot the latter part of my instructions and once he crossed the hedgerow, he kept going. I soon realized that I was not going to be covered for my withdrawal and so I ran and jumped the hedgerow myself.

Much to my embarrassment, as I jumped the sticker bush hedgerow my foot caught the top of the fence. Further, as the field on the other side of the hedgerow was about four feet lower than the field where I started, my poorly judged and executed jump caused me to land on my head. In a moment, I stood up dazed and found myself looking down the business end of the muzzle of a German Luger. My pistol lay on the ground, and I was in no position to argue the point with him when he yelled, "Hands up!". He asked for my pistol, and I pointed to the ground. He reached down to pick up the pistol as I glanced across and saw that my friend, Private Ford, was returning. I quickly reached down and grabbed the German's hands, his pistol in one hand, my pistol in his other hand. Private Ford, who I later learned was an expert marksman, fired twice from the hip and struck the German square in the middle about two inches under my arm. The German folded like a sack of wheat, and we took off like a couple of sprint runners. (ed. note: Pvt. Ford later received a Silver Star for his actions in this regard.)

In my haste to escape, I was unable to retrieve my pistol. By this time, it was about 4:00 AM and dawn was beginning to break. We ran for a little village and hid for a few minutes in a barn to catch our breath. We soon realized that this barn would certainly be searched and so we headed for the open fields. The spring foliage covering the deep hedgerows made excellent cover and we were able to find a very cozy little spot to secrete ourselves for the moment. We were quietly eating our Hershey concentrated candy bar when we heard noise just outside of our hiding place. We looked around and found that the Germans were setting up machine gun nests all around us. They were obviously completely unaware of our presence. So, we remained burrowed in the hedgerow all day until dark.

When dark fell, we slipped out and found a little trail. We wandered along the trail hoping desperately to find some clue as to where we were. We had puzzled over our maps all day. At the end of the trail, we came upon sandy stretch of open ground covered by barbed wire and German signs saying, "Danger Mines". We fully realized that we should go to the east to join the other American soldiers. All night long and even now there was the sound of heavy gunfire in this direction. So, on our hands and knees we carefully crossed the sand, trying to stay away from mines. To our good fortune, we did. When we got to the water, after attempting to ford what we thought to be a river, we realized that it was too broad to cross. Little did we realize that this was the English Channel. Drenched, we wandered on further to the North along the beach. Soon we came to a small town, but we still could not find any signs of the name. Nothing we saw looked familiar. We saw a barbed wire enclosure around a large building and wandered up to take a look. Imagine my surprise when I peered through about three feet of barbed wire entanglement to see a German peeping through, obviously as curious, at me. My only weapon was a hand grenade, and I grabbed it and pulled the pin. He was apparently as surprised to see me as I was him and he took off like a shot. A grenade won't go off unless the handle is released and so I held it down and ran myself. I finally found a rusty nail and placed it where the pin usually goes in the hand grenade. I put the grenade in my pocket and didn't think of it until a month later.

Pvt. Ford and I wandered through the town and on out further to the West, having given up the idea of trying to cross to the East. We wandered around all night trying to figure out where in the heck we were. As a kind of a token of our dislike of the Germans, we placed a demolition charge under the railroad track near the crossing in town. When dawn came, we were apparently several miles to the West and South of the little village. By this time, we were getting pretty hungry and were pretty tired of our chocolate bars. We saw a couple of young French teenagers in a field, so we went over and tried to talk to them. Neither of us had any knowledge of French and these young people knew no English. We had a little booklet which told us how to speak French and by pointing to it and the American flag sewn on our shoulders we tried to explain to them that we were friendly American soldiers. By good fortune, these children were from a family that was a part of the French Resistance Movement. (ed. note: after the War we learned that the French family had made a conscience decision earlier that they would assume the inherent risks and assist any liberator/invaders.)

The teenagers took us to their home where we finally convinced the family that we were Americans. Apparently, some Germans had earlier disguised themselves as Americans to try to get the French to divulge who was heading their underground movements. They took us in and fed us warm soup, dried our clothes, and began a celebration which lasted 24 hours. We were taken later that afternoon to the home of Mdme. Lefilliastre. (ed. note: a beautiful French Chateau and large farm.) Soon all kinds of people began to come in. They all brought some token of appreciation to us, the great liberators. Much wine flowed. It was quite a celebration. An elderly lady in her seventies, who was the English teacher in the local village, had walked eight miles to be our interpreter. Much to our amazement, we had landed on the outskirts of Saint Vaast-la-Hougue, which was about 25 miles from where we were supposed to be. Actually, we were closer to Cherbourg, one of the primary goals of the invasion, than to the invasion beaches.

The next day, as we were making plans to leave and follow the route on the map prescribed by our friends in the underground, a thin young French boy, dressed in a black leather coat with tight black pants, black beret, high black boots and a black bicycle appeared. He looked like a French Resistance courier that had just stepped out of an American movie. He also carried a message to me which was in the obvious place for a good movie thriller, the inside of a heel of his boot. The message informed me that I was the Senior ranking officer of approximately 50 men who had dropped scattered in that general vicinity. They stated that they would like to get us all together and guide us back to the main body of our airborne troops. We readily agreed to this arrangement and delayed our leaving until our moves were coordinated by the underground.

Unfortunately, the Germans knew we were somewhere in the vicinity and German troops began to search the houses during the day. We were downstairs talking to the French people when Germans appeared. French guns, as well as, the M1 rifle which Private Ford had with him, were assembled. I hid behind a big armoire and Ford was posted in the attic. Fortunately, they only came to the door and did not enter the house, so no fight was necessary, but we were all ready.

That evening another celebration began. This was to celebrate our leaving. Far too much wine (and Calvados, a French Apple Brandy) flowed and, although I realized that we should quit drinking early, my companion Private Ford, did not. When midnight came and we were supposed to leave, he was in no position to carry his weapons, equipment, and almost himself. I supported him until he had gotten enough fresh air to recuperate and travel under his own power. That night was really quite an exciting one. We snuck through narrow trails that were well concealed, up and down hills and through fields and passed within yards of German patrols, which these people had completely timed, calculated and plotted. Dogs barked at us, and we were sure that we would be detected. In the middle of the journey, we went into a house in very small village, I have no idea where this was. We roused the people out of bed and one of the prettiest women I have ever seen came out in her nightgown and gave us all a big kiss. Her husband brought along some cognac, and we again celebrated the liberation of France. Just before dawn, (4 AM) we reached the home of Mdme. LeVaillant. We had been guided that night by two of the bravest young (French) men, just sixteen years old, that I have ever known. We were placed in a barn of the LeVaillant home and remained there all day. As this farm was near the main highway connecting Cherbourg and Saint Vaast, we could see German vehicles dashing up and down the road by us all day long. We could tell that they were really nervous.

About an hour after dark that night we were called out and there met two officers and twenty men of various scattered units from the 82nd and 101st Divisions. Together, guided by a new set of young French men we took off to the East. We traveled little trails and across open country, mostly in the valleys and along small streams where we would be hidden completely. It was rough sledding through this beautiful farming countryside. We had no narrow escapes, nor did we see or hear any Germans on this particular evening. At about dawn we reached the group soldiers which made up the balance of the fifty soldiers we had been informed of. Among them was a Captain, several Sergeants, and enlisted men. These soldiers were mostly from the 101st Division. Since I was the only officer who had previous combat experience, I was named commander.

We set up a defense around the four sides of a square field, taking positions and hiding in the hedgerows. The French people of the underground agreed to bring us food until the next night when we were to be slipped through the lines back to our own units. At this point, I estimate that we must have been about seven miles from our front lines. But we weren't the only ones who had plans for this area. German troop movements began to take place all around us. Instead of moving out that night as we should have, we sent out scouts to see just how heavy the concentration of German troops was between us and our lines. Our scouts didn't get very far before they came back and said that it would be virtually impossible for us to get through. In the meantime, the French underground people became afraid that they would lead the Germans to us when they brought food and so they chose to quit bringing food into our area or coming to visit or guide us. We were really trapped, and we knew it.

Early the next morning a heavy German artillery outfit moved into the field immediately adjacent to us. As an artillery man, it was quite an experience to see them move into position, they were very efficient. That night we silently slipped out of our encampment and moved about two miles to the South. It wasn't an easy move. One of our men was injured. Everyone was unhappy and we were beginning to get hungry again. We had a 50-caliber machine gun and a couple of heavy radios, all of which we decided to leave because they were of little use to us. We dug holes, buried them, and then camouflaged the equipment. Our new location turned out to be no better than the old one. German troops moved in all around us again (as they were retreating and/or setting up defensive positions against the advancing American Army - approximately D + 7).

By this time, two Germans had wandered into our area, and we took them prisoner. So here we were, completely surrounded by Germans who were unaware that we were there, with two of their own people as prisoners inside our little group. Soon not only food but water began to run out. Days passed and we knew that our only hope was that American troops would run the Germans out of there without having a heavy fight in our area pinning us down in the middle of a battlefield.

A number of interesting things happened during this time. We had with us a Sergeant of Polish descent and I never knew anyone who hated the Germans more. Every night he would go out and cut the telephone wires of a German line. The telephone repair crew, usually consisting of two non-combat men, would come. He would trap them, disarm them, make them dig their own graves, then shoot them and push them in. His hobby was collecting ears. He had a little plastic bag with quite as collection. In another incident, when I was trying to scout out an exit from our trap, a German walked up within about ten yards of me. I laid down, relatively unconcealed, and motionless in the ditch. He never saw me, walked right past and on down the road.

Then it happened. We were detected. Late one afternoon, strictly against my firm orders, some of the men got so thirsty they gathered up a bunch of canteens and tried to sneak down to a little stream near where we were holed up. They must have been seen but apparently the Germans who saw them didn't realize that there was such a number of us. A small detachment was sent to take the Americans. They surprised us but it wasn't long before we were putting up quite a fight. By this time, dark was falling, and I yelled at all the men standing around me to follow me and make a run for it across the field. Twenty-three of the men and one other officer followed. The rest were just about at the end of their ropes and stayed and surrendered.

We were all pretty well acquainted with the terrain around us, so we ran down the ditches and across several fields. One spot in which we found ourselves was most amusing. We ran out the end of a ditch and found that we were amid a German artillery position. I was leading and as an artillery officer knew that artillery soldiers were lightly armed and not the best of marksmen. In addition, they don’t expect enemy infantry to run through their positions unannounced, so, with the twenty-four men strung out behind me, we ran right between the German guns with all their men standing around surprised with their mouths open, not moving. It wasn't until we were pretty much out of close range that they found their weapons, took up their arms and began to shoot. By this time, it was fully dark, and we quickly eluded them. I left the men hiding and went out in search of a better place in which to seclude ourselves. Private Ford was still with me, and he and I took on the task of finding an exit from our situation.

We found a road and were trying to see which way it went when we heard some German tanks and troops approaching. We laid down in the ditch and covered ourselves with brush. It was quite a feeling to have their tanks, trucks and men pass within inches of where we lay. We could have reached out and touched any of them at any time. I gathered from what was going on that they were really looking for us and so we decided we'd better get the heck out of there.

The men, not having eaten for several days and running so much, were pretty much exhausted. I put the other officer at the head of the column, and I stayed at the rear, waking them up as they fell asleep and fell off the path. We walked several miles before finally lying down in the ditches of another hedgerow surrounded field. Somehow, they must have known we were in that area because early the next morning they came and shot up and down the rows and ditches of all the fields, including the one we were hiding in. By some amazing stroke of luck, not a soul was touched, but we were pretty shaken. We sat around that night and discussed what was our best plan. We decided that we would split up into small groups and try to quietly infiltrate through the back of the German lines and into the teeth of the advancing American line. It was with a heavy heart that I saw Private Ford and the Polish Sergeant take off together down the road.

It wasn't long before some of our men apparently had wandered into a bad spot. Gunfire signaled the fight they had gotten themselves into. There were four of us together and we went back to a small farmhouse where we found some rabbits in a pen. We took them and went out into the country and made a very small fire with relatively little smoke. It wasn't many minutes later that we ate singed, semi raw rabbit, one of the most delicious meals I can remember. We had been without food for almost seven days. I had lost over thirty pounds. It was about D+11, hungry, tired and behind enemy lines. It's funny, however, the things you do. I had a small razor kit with me and had made a special point of shaving every day, keeping my appearance as neat as possible in order to try to bolster the morale of our men.

We were sitting around resting after our meal when a German walked right into where we were. He was unarmed and took off like a rocket. We, too, moved out quickly but soon heard a group of them coming after us. Having been a student of American movies, I directed the men down into a stream and there we submerged ourselves, putting straw reeds into our mouths for breathing. We spent most of the afternoon there and were never detected. (ed. note: this was very cold water.)

Later that day we found a farmhouse nearby. We set ourselves up around it and watched it for the balance of the day. There were a number of people moving in and out, but no Germans nearby. We decided to take a chance and go down and see if these French people would offer us food and shelter. They were very nice and, strangely enough, the boy in the house was a college student and spoke some English. We had hardly gotten anything to eat when he began a dissertation on the politics in France, De Gaulle, et cetera, et cetera. At this point, we couldn't have been less interested. They hid us in the barn, and we decided to stay there until our troops came through.

According to these Frenchmen, the Allies were not far away. This soon became quite obvious because artillery shells began to land in and around the farmhouse. German troops were nearby and several of them came through but never looked in the barn where we were hidden. Another two days passed, and things suddenly became very quiet. Our French friend came in and informed us that the American troops had passed close by, and we were now in American controlled territory.

Soon we contacted the nearby American troops with a note and were guided into their area. It was the American 4th Infantry Division. I don't think I can ever express how happy I was to get back with our fellows. We had been 21 days behind the German lines. They took us to their division headquarters where we were asked a number of questions by the G-2. He puts us up for the night and loaned us his jeep the next morning, sending us back to the 82nd Division area. We thought that we were returning as heroes, having gone through a tough ordeal, and saving our skins to fight another day.

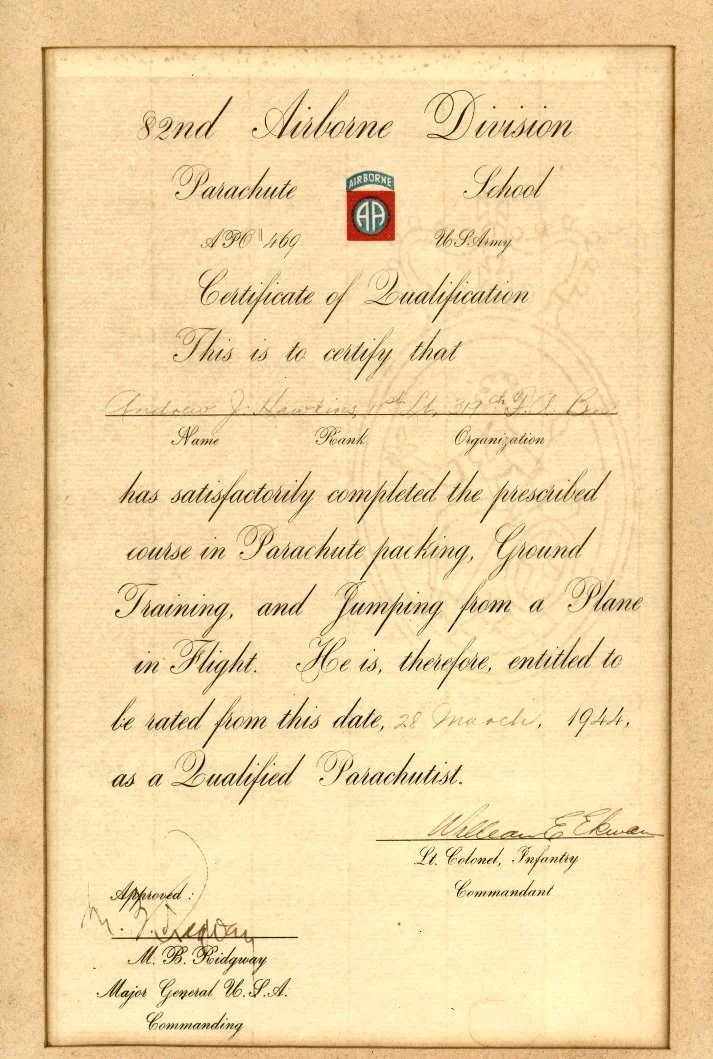

At Division Headquarters we were politely asked a few questions and then sent back where I reported in to Colonel Todd, our battalion commander. I thought he would be so happy to see me. He looked up and said, "Where in the hell have you been? Off with some French girls, I'll bet, having a party. Don't you know there's a war on and we need you for fighting. Get the hell out in the front lines and go to work!" All of this was said with relatively good humor but in a serious voice. The Doctor was my close friend, and he came in and interceded in my behalf. He told the Colonel that I had been through a very harrowing experience and might be a good mental case. He was given permission to keep me overnight in his medical tent for observation.

We went back and started one grand celebration with the medical alcohol that was given for severe cases such as mine. I didn't let this start, however, until I made a point to go over to see my good friend, Chaplain Reid. I never saw anyone happier than he was to see me. Tears came to his eyes, and we said a little prayer together. He told me how he had finally given up. He had even gone through the ruins of charred planes and the bodies of the men in the morgues trying to find me. We all caught up on our recent events. After having eaten quite a bit and finishing-up our celebration, I remembered the hand grenade with a rusty nail in place of the pin. I took it in and put in on the desk of the supply officer. You never saw a place clear out so fast.

I had been carried "missing in action" and my parents had received a telegram that I was missing. I don't think they ever recovered from this terrible shock. Notices were put in some papers that I was dead, and it wasn't until after the war that many of my friends from college knew I had not been killed in the invasion.

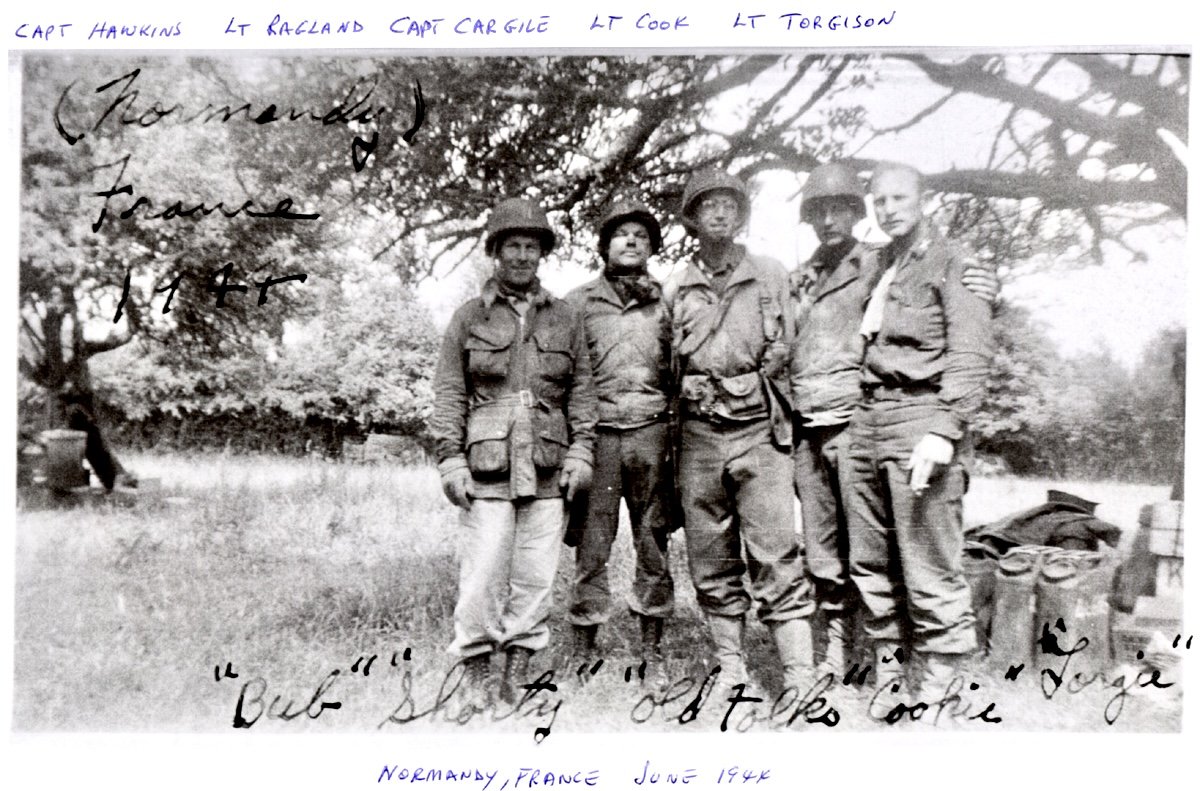

True to the Colonel's orders, I reported to the front lines the next morning and found Colonel Lundquist, Regimental Commander of the 508th Infantry. I became Regimental Artillery Liaison Officer and helped direct our three batteries with a total of 18 guns in support of the Infantry. We fought near the small tower of La Haye du Puits. I remember the beginning of an attack at dawn on July 4th. I was in a ditch just prior to jumping off the attack. Both sides where shelling heavily with artillery and mortars. A mortar shell landed right next to me covering me with dirt, but I didn't get a scratch, the two men who were on each side of me were killed. Later the Infantry ran short of men, so I headed up a patrol. For this and other things, I was awarded a Bronze Star and Combat Infantryman's Badge, the latter very unusual for an artilleryman. Incidentally, I never received any awards for my harrowing experiences behind the lines. To add insult to injury, I even had to pay for my meals during my absence, as all officers do when they are on active duty.

It may be interesting to know the experiences of Private Ford from the time he left me. He and the Polish Sergeant wandered into a house and found a chicken. They built a fire in the stove and began to cook it. They weren't so careful about the smoke and soon the Germans came and captured them. They were taken to Cherbourg and there were placed in prison. By this time, the peninsula was cut off and Cherbourg was surrounded. They were moved from one prison to another and finally to a fort where they were to be picked up and taken back to Germany. During one of these moves the Polish Sergeant was hit by fragments from an American shell as it struck a building near him. He was killed. Ford, along with a number of other men, were never picked up and were not taken back to Germany, although the two officers who had been with us were. Ford was finally liberated when the Americans captured Cherbourg and returned to duty with the 508th Infantry. I saw him frequently after this. He lived through the War but never went above the rank of Private First Class - and never wanted to. He did however receive the Silver Star for saving my life on June 6th when he eliminated the German that had captured me.

Before I returned to England, after we had been pulled out of action and were awaiting transportation aboard ship to go back, I got permission to take a jeep and visit the members of the French Underground who had befriended me during my experience behind the lines. The French people were extremely happy to see me, and we had more celebrations. I also found out that members of the French Underground had found my possessions that I had left in the barn. My military issue items had been given to the first American troops who came into that area but several of my personal items had been kept for me. I still have my knife and a hat that were stored there.

I tried to learn the fate of the other people who were in the plane with me. Of the eighteen, only three of us, Private Ford, the German Intelligence Sergeant, and me, ever got back to American troops. There was no trace of what had happened to Sergeant Sample and, although I heard many stories while trying to find out, nothing firm could be learned at this time. I might go on to add that after the war was over, on the first anniversary of D-day, June 6, 1945, I was sent back to see if something could be found out about the disappearance of these men who had never been reported as prisoners of war and no sign of their bodies had been found. Upon investigation, and after following a thin trail of tales, we discovered some unknown graves that had been moved from the area where we dropped to the American cemetery in Saint Mere Eglise. We decided to exhume the bodies from one particular grave where the description sounded somewhat like Sergeant Sample. I had his military record and dental chart with me. It was a most terrible experience. There was relatively little left of him, but we did find his skull and after washing his teeth with my own toothbrush, I found a dentist from a nearby Army Hospital who was able to positively identify this as the remains of Sergeant Sample. He and the six other men who had dropped into the adjacent field next to me were apparently lined up and shot in cold blood. This seemed to be a venting of the wrath of the German military commander who had lost several men in the fighting the night before.

In late July, we were put on LST's and returned to our headquarters in England. We had lost quite a few men our Division casualties were about 30%. We were given a two-week holiday. I went to Edinburgh, Scotland and had a most enjoyable time. We returned and got back to rebuilding our group and restoring our equipment to fighting shape. We were then part of the 18th Airborne Corps. Several missions were planned but were canceled because of the fast-moving Allied advance through France.

On September 17, 1944, we were taken by air to Holland in Operation Market Garden. The 101st Airborne Division dropped closely behind the British lines in Eindhoven, the 82nd Division dropped in Nijmegen and the British dropped in Arnhem. I went in a CG4A Glider in this operation. This was a very flimsy craft made of plywood, aluminum tubing and airplane cloth. We were towed by DC3's carrying parachute troops and supplies.

When we got above the English Channel, you could see layers of planes in all directions as far as the eye could see bombers, fighter planes, troop carriers and gliders. It was an awesome sight. We encountered heavy flak as we crossed over the marsh lands of Holland. Eventually we approached and landed in the midst of a field where a heavy battle was taking place. Germans were standing in this field firing rifles at us. Our glider pilot dipped our glider down at a German soldier directly in front of us and hit him square on. Fortunately, for us, the confusion was so great that we were able to quickly get our artillery pieces and form up into a group reporting to the area where we became a part of the operation. At this time, I was Battery Commander of AB Battery of the 319th Field Artillery Battalion. We were supporting the 508th Parachute Infantry again.

The British quickly ran through the 101st and then had a bit of trouble getting into Nijmegen. In the meantime, we were under quite heavy pressure. Fighting was all around us and we were being re-supplied by air drop. I again took over liaison with the infantry because of my previous knowledge of this type of work and my friendship with the 508th commanders.

Several days after the landings we were out looking for an observation point and apparently wandered beyond our front lines and behind German lines. We met some Dutch people who were members of the Dutch underground called "Orange”. They were very nice, fed us, and showed us much of the country thereabouts. We found a lookout tower where we could really see everything around us. We were just about ready to set up shop when along came some German Messerschmitts and machine gunned us. Fortunately, although they riddled the tower, they hit no one and we soon found that this was not a very healthy location. We were surprised to find we were beyond our front lines when we returned. Shortly after, the Germans shelled and bombed the home of the Dutch people where we had visited and cut down the observation tower.

Later the British Armored Corps did reach Nijmegen and we became part of the major front line of the then stagnating Winter Line. Our troops were moved across the bridges, and we were the very Northern tip of the Allied front.

The British troops never reached their own paratroopers in Arnhem, and they were literally decimated. This was very sad to me because I had lived with the British 6th Airborne Division for a month during training in England. Many of the fine men of this organization were killed. I feel the responsibility is that of the British Armored Corps who certainly did not put up their best effort to get their men out of an untenable position. Intelligence after the war, contained in the book A Bridge Too Far by Cornelius Ryan, confirmed that the stubborn, egotistical attitude by British Commanders, General Montgomery in particular, caused this operation to fail. It really should never have been undertaken. Although we were not equipped for prolonged fighting, we were held in the front lines from September until late November. Finally, we returned to what then became our base camp near Reims, France.

We were all set for vacation relief. Some of our men went to the Riviera. Others were sent to England. I chose to go back to see friends in England. Two days before I was to go back, the Germans broke through our extended line in the Ardennes in the “Battle of the Bulge”. This put an end to all our plans.

Overnight we were reequipped, pushed into trucks, and sent to Belgium. We passed through Bastogne, just missing the leading tanks of the German onslaught. We took positions near St. Vith, not far away. Of all the fighting we were ever exposed to, this was perhaps the most severe. We were certainly not equipped for the snow and the type of operation that existed here. It was very discouraging to see us with our small arms and little 75 mm pack howitzers holding the front line when our own tanks, heavy artillery and troops were passing through us, the most beat up looking individuals I ever saw. They were indeed a poor example of American fighting men. They had been ill trained and were not prepared for the German attack. They soon became demoralized and were able to put up absolutely no defense. We pushed our position forward and got as many of these people out of that spot as we could, and then, for the first and only time in the history of the 82nd Division during World War II, we retreated. We were successful in our retreat and after some rather rough fighting, we decided to attack and regain our position. In a few weeks the situation stabilized. We continued to be part of the front and remained in the fighting through December 1944, January, and February 1945. Afterwards we again came back to Reims.

In April, we advanced to the Rhine River, the German Army was fighting but retreating on the other side of the Rhine. Most of the German Army was on its heels and trapped in what was then known as the Ruhr pocket. By this time, I was assistance operation officer for the battalion. With relatively little going on, I decided to try airplane observation. We would go out each day and take a tour of a couple of hours up and down the Rhine River trying to observe German movements on the other side. Somehow, I was jinxed. These planes could fly other observers all day but when I got up, somebody would always start to take pot shots at us. But we had plenty of fun shooting back and adjusting our artillery against them. So long as they didn't hit us, it didn't seem to bother us too much.

Finally, we learned that the American 13th Armored Division was coming up from Bonn on the other side and had more or less cut off the Germans from the area across the river from Cologne. About three o'clock one morning I got a telephone call saying that there was heavy fighting going on in front of the 13th Armored Division and that I had been requested by General March to make air observation to see if we could help adjust our artillery and assist the armored division.

At dawn we went up, after a slight adjustment. When we approached the airfield, Lt. Morgan, who was my pilot, was very mad because apparently his sergeant had failed to fuel his plane the night before. We went over to his friend's plane and used it, which later turned out to be the salvation of both of us. Lt. Morgan’s friend had an experimental radio mount on his plane wherein the radio had been lowered from above shoulder level to seat level. The area where the radio usually was located had been opened and plastic had been placed there forming a rear window. The reason for this was that several our artillery observation planes had been shot down by German fighters sneaking up behind them. The plastic was to improve the rear visibility of the observer so that he could spot anyone from behind.

That morning we went up and down the river, but since it was early morning and we were looking east, the fog and the haze with the sun in our eyes, limited our visibility to almost zero. We had been firmly told not to cross the river. We had a choice to make. Either we could fail in our mission and not help the armored people or we could disobey orders and get to where we could see what was going on. We chose the latter, principally because Morgan had been a soldier before getting his commission in the 13th Armored Division. He felt as though he wanted to help his old buddies.

We decided to play it safe and flew down below Cologne to near Bonn. I knew that Patton had taken Bonn and it would be safe to cross the river there. We then turned up and kept a steady observation on the American vehicles. We felt pretty safe as long as we were behind the front lines of our people. By this time, Morgan's curiosity had really gotten great, and he decided to try to find out if this was the armored unit of the 13th Armored Division that he had been attached to. We got down to about fifty feet off the ground and I was trying to read the numbers on the vehicles. We were so absorbed in this unusual effort that we suddenly crossed over the front line of our tanks and the first thing we knew we were looking down at German helmets.

Being about fifty feet off the ground, everything they had was cut loose at us. Pistols, rifles, hand grenades, anti-aircraft guns, machine guns and everything they could find to throw at us including rocks. Morgan put the plane into a sharp turn just as I saw tracer bullets come up on one side. I heard something, felt something, and saw them go off the other side. We (and I) had been hit in the tail. (ouch!). Morgan temporarily lost control of the plane but soon gained some limited control. He asked if we should try to get back across the river to our people and I told him I had been hit and wasn't feeling too good. He decided to crash land. There he dropped between two of the leading tanks of our units. The Germans kept shooting at us and shelled our tanks and our plane. As soon as we got out, they hustled us into a tank and there tried to give me some first aid. We accomplished our mission of finding the retreating German Army but at a cost. Even though, however, I received the Air Medal for successfully completing this mission.

I had been hit in the elbow (funny bone) and back. I didn't know how seriously. Soon an ambulance came, and I was taken back to a small hospital. I was so mad at myself I couldn't stand it. I had been overseas for thirty months, had been in six major battles, had almost every experience a person could think of, but had always been careful enough to keep myself from being killed or wounded. Here it was, very obviously towards the end of the whole mess in Europe and I had gotten myself shot. And strictly doing what I had given so much of my time training my people about - and that is not taking unnecessary chances. In any event, I was eventually repaired slightly and put aboard an airplane and sent back to a hospital in Reims. There I found one of the nurses I had been dating was taking care of me. They decided I needed an operation to get the lead out of me and so they sent me to another hospital in Epernay, France.

I was operated on twice and was in the hospital 10 days later on May 5 when hostilities finally ceased. I received a couple of notes from some of my buddies telling me I'd missed out on all the looting and the fun part of the war. I was really mad.

I remained in the hospital for a few days until I had fairly well recuperated and then was sent back to our base camp. There I found an old friend, a captain, who had come back for the general's Packard. We decided to drive it together back to him in Germany where our outfit now was.

By coincidence, we arranged our timing and routing in order to be in Brussels on V-E night. This was an experience I'll never forget. People were tremendously happy. The whole town was one whole mass of humanity parading, celebrating, etcetera. We spent the night there and the next morning drove up to meet our troops. There we became the occupation troops in a small-town call Ludwigslust, Germany.

We were across the Elbe River and on one side of the town were our troops and the Russians were on the other. General Gavin was our division commander and quite a man. We remained here for about a month and then were taken back to our base camp in Reims. All of us who had been in the service for a long enough period and desired to go home were allowed to join the 17th Airborne Division. Many of the young troopers from other divisions, who had not been overseas long, were taken into the 82nd and the Division was sent on to Berlin as part of the first American occupation troops in that city. The veterans remained in Epernay, not being sent home because priority was given to troops that were being rushed through the United States to the unfinished war in the Far East. Before they got there, however, the War in the Pacific was over.

In August 1945, the world war was over and we were sent to Marseilles, France and then by ship back to Boston. From Boston we were abruptly disbanded to our homes and immediately taken out of military service. It all happened so fast we didn't know what happened. We even forgot to tell each other good-bye in many cases. In November 1945 I went back to work with DuPont in the rubber laboratory. They were kind enough to reinstate me and my service. I remained in the reserves for about 2 years after the war and eventually retired as a Major. It took a couple of years for me to settle down, get married and start a family.

Editor’s note: In 1986 A.J. Hawkins retired from DuPont as General Sales Manager of the Western Region Elastomers Division after a 45 year career with DuPont. He died of cancer in 1989 after 42 years of marriage to Lorraine McNeil Hawkins having raised five children. The family to this day stays in touch with and visits the French Resistance families in Normandy, France.

Frank Kondratick (L-R) Reuben Engel, John Gutshall, Andrew Hawkins, Richard Johnson - December 1944

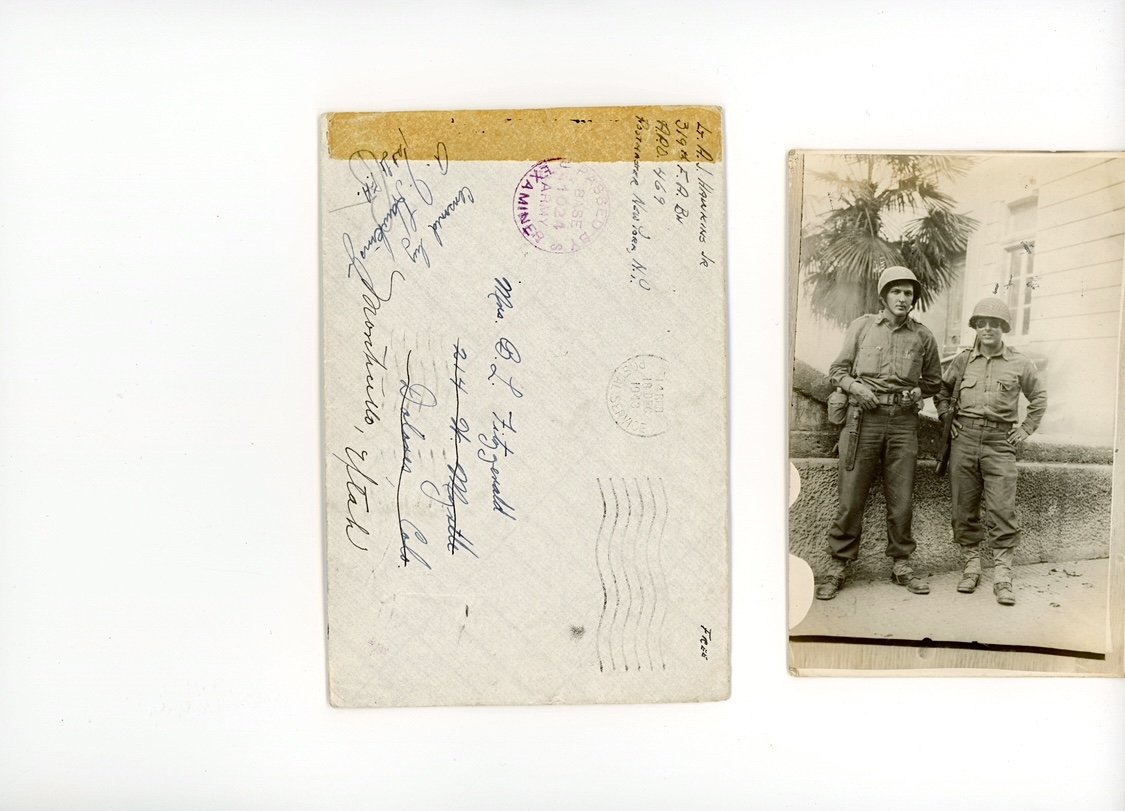

Hawkins, Andrew J. jr., Captain: Bronze Star Medal, AM, GO 36, 1944, GO 128, 1945.

O-415323, for meritorious service against the enemy on the morning of fifteenth April 1945, at censored Germany, Captain Hawkins volunteered to fly a reconnaissance mission to observe enemy movements and installations. Finding his assigned sector clear of both he turned to an adjoining sector, flying behind German lines to plot the location of enemy troop activity and gun positions, through thick fields of antiaircraft fire. Returning to American lines the plane was hit, fragments ripping into the vitals of the ship and wounding Captain Hawkins. The plane managed to limp safely back to friendly lines, and although suffering from his wounds, Captain Hawkins refused evacuation until he had reported the results of his mission to our artillery. His courage under fire and outstanding devotion to duty above his own comfort in this action was in keeping with the highest ideals of the airborne forces. Entered military service from Atlanta, Georgia.

See the Capt. Hawkins War Memorial in France

Twenty Minutes Under Fire

By

1st Lt A.J. Hawkins, Jr.

The morning of September 17, 1943:

I slept out on the point that night at on outpost on Mt. Angelo overlooking the valley in the rear of the German Salerno defense. I wanted to watch for lights and listen for troop and convoy movements, which were clearly audible from this place, so that I could adjust artillery fire that next day into the places where the most lights and noise occurred. I slept part of the night wrapped in a blanket, about ten yards from my foxhole. About 0300 hours I became so cold that I got down into the foxhole (a hole behind a bush 3 feet square and about 4 feet deep) to get out of the wind, and I know for a fact that there is little sleep in a foxhole. At dawn, about 0630, I got out and spread my blankets on the ground for the sun to dry the moisture out of them. As I was about to check my communications to begin firing --- zsssss--- crack! A shell landed about 20 feet from me, and fragments flew everywhere. I dove for my foxhole yelling to my men to do likewise and in the rush forgot my helmet which was by the blanket. This was the first shell of a 20-minute concentration. At first, I thought it would only be one or two shells, but a second later ---zip---crack---frrrr, (have you ever heard a covey of quail pass close over your head? Well, that’s the way shell fragments sound passing over) dirt fell in my foxhole and the dust and powder smoke was suffocating. I was then firmly convinced that the Germans had seen me get into that foxhole, and that I’d never get out of it alive, so I said my prayers and said I was sorry for all the bad things I had done. I waited, and of course scared worse than I have ever been scared before and shaking all over. I kept worrying about my helmet, and since I didn’t have it on, pushed my head down in the lowest corner of the foxhole. Shells were landing all around (I found later they covered an area of about 50 yards by 100 yards) when I thought of the box of hand grenades that was near the top of my foxhole. Cautiously I reached up and gave them a push, sending them rolling down the hill. All the while the noise was deafening, and it kept my ears ringing. My throat was burning, mostly from fright and partly from the smoke and dust. I thought of how foolish I had been to stay out on the point and how the other officers were safely on the other side of the mountain. (I found later that they too had been shelled from another direction). I thought of my men and hoped that their foxholes were as good as mine. There was a lull in the shelling, and after two or three minutes I yelled, “Is everyone O.K?” There was no answer and an awful spell of sickness hit my stomach, they were all killed, and I knew it. I crawled out of my foxhole and began looking where I had left them. Not a soul was in sight. All had gone back during the shelling, except me, and there I was alone. I began to look around but stayed close to a foxhole in case they started again. Equipment was all over the place, telephones and lines were all shot up, a water can sitting about five feet from where I had been during the shelling looked like a sieve, but the water cans in the hole where we kept them to keep the water cool, were in good condition. The ground looked like Mother’s garden just after “Old Dave” had turned it over, and had forgotten a few spots. Even the limbs and leaves of the trees and bushes were torn off. I crawled (I knew they were watching and if they saw any movement, it would begin again) over to my blanket and it was full of holes, my leggings that I had taken off the night before had been ripped by a shell fragment, and my helmet had a little crease where a fragment had glanced off of it. I gathered up my equipment and crawled over the crest where I found my men. Only two out of the twenty had been hit and there were no serious wounds. Later we established communications by running a line back down to the outpost, this being done with the aid of men who were not under the fire and who had seen where the enemy guns were firing from. I directed fire on those places, and we never heard from them again.

I reckon it was my Mama’s prayers that kept those shell fragments out of that foxhole that morning; but then a fellow has to be careful and not expect his mother’s prayers to go too far. Do not unduly expose yourself to danger, there is plenty without looking for any.

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4