Elden Smith

ASN:35136988

Elden Smith was an enlisted man from Lincoln City, West Virginia. Smith registered for the draft on July 1, 1941. Born May 19, 1920, he was 5-6, 149 pounds with a light complexion, brown eyes and black hair. He joined the US Army on March 28, 1942, at Fort Thomas Newport, Kentucky.

He trained at Camp Claiborne in Rapides Parish, central Louisiana. (During World War II over 500,000 men and women were trained at Camp Claiborne, learning everything from basic riflery to railroad operations to sophisticated engineering skills.)

PVT Elden Smith - Camp Claiborne May 1942

Elden Smith then transferred to Fort Bragg, North Carolina and joined B-Battery of the 319th which was now an airborne glider artillery unit of the 82nd Airborne Division.

Like his fellow glidermen, PFC Elden Smith set sail for Casablanca, Morocco in Northern Africa in May of 1943. There he received training until September and then was shipped to Italy, where his unit invaded the beach town of Maiori on the Amalfi Coast. Elden saw action in and around the city of Naples and in November, of that same year, sailed from Naples to Northern Ireland for rest and more training, then on to Market Harborough, England. This sizeable market town was located in the district of Leicestershire, about 90 miles northwest of London.

This was the spring of 1944 and Market Harborough was a Royal Air Force Station and operational training center.

Elden had been trained to be a gunner, or cannoneer, on both a 105mm and 75mm howitzer (artillery pieces with a 7-foot barrel that were used to shoot enemy targets on the ground, on the water, or in the air.)

On the night of June 6, 1944, Elden Smith and the 319th Field Artillery Battalion glided into Normandy, in northern France as part of Mission Elmira. They landed two miles north of the town of Sainte-Mere-Église just before 11pm local time. This was D-Day!

Elden and his fellow glidermen were an integral part of the largest amphibious invasion in the history of warfare. Elden Smith tells his own story of his exploits during World War II in a series of letters he wrote to his beloved niece and nephew, Jacky and Bill.

The following stories are direct quotes from Elden’s letter. While the stories are not always in chronological order, we’ll begin in northern France, on the southern coast of the English Channel, during the Normandy Invasion.

The Elden Smith Story

Normandy was one of the most consequential battles of the war. The casualty rate on D-Day was staggering. More than 226,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing. But the Allies won the day. And most historians say it was the “turning point” in the war in Europe.

NORMANDY:

After landing without injury in a British Horsa Glider, Elden Smith, and other members of the 319th Field Artillery Battalion (the glidermen) made their way south, towards the German’s front lines.

The following story took place around June 10, 1944.

“The dead bodies of paratroopers and enemy dead were already starting to stink when we moved into position in the apple orchard overlooking the small town (Ste-Mere-Église) that was near the Merderet River.

The battle for this town and the bridge across the Douve river was one of the most violent we had while in France. It was our hope to take the bridge intact.

We fired hundreds and hundreds of rounds of 75mm shells, and the Air Force dropped many bombs on the enemy. Finally, we drove the Germans out and moved forward. But the next bridge had to be rebuilt. This task fell to the combat engineers.”

Photos courtesy of Allen Stabenow

NEW PONTOON BRIDGE:

“We moved up the road and took our position in an apple orchard. The engineers followed. We stood watch - under a full moon - to give them protection while they worked through the night to build us a new bridge. Come daylight, we were staring at a brand new pontoon bridge. Now we had to continue to chase the enemy!”

TANK BATTLE:

Wallace Edwards (L-R), Elden Smith, Ray Stabenow

“That job fell to the #1 gun section, our group of about 25 men. We were the first Americans to cross this new bridge. We pulled our 75mm howitzer across the bridge, through the village, and down a road about one mile until we met a small enemy tank. When we heard the tank coming our men left the road and hid in the bushes. We let the tank go by us.”

“Sergeant Wallace Edwards then said to me, ‘Smith, fire at anything that comes up out of that dip in the road.’ Now the odds were in our favor. Our howitzer was loaded with an armor-piercing shell and five charges of powder. We had 9 shells all together. We only needed one.”

“After the howitzer had knocked out the German tank our paratroopers up front, who had been hiding in the bushes, killed what was left of the enemy. There were 16 dead Germans around the tank and 2 dead inside. Not one American got a scratch. My guardian angel must have been watching over me, again.”

“From the time we left the apple orchard until the battle was over was less than one hour. We had practiced just such a confrontation many times during our training in Africa and England. It paid off. We left the road and set up positions in the field. Now four more howitzers came into position and we were giving the enemy hell again - for the second time in less than two hours. But those 16 Germans laid in the road for 3 or 4 days. We had to drag some of the bodies out of the way so we could get by with the Howitzer. They were stinking when a truck finally came and picked them up.”

Capt. Andrew Hawkins - Papillon Hall 1944.

“Our success was thanks to good intelligence from our forward observer, Lieutenant Frank Poole. In my opinion, he was the best forward observer the Army ever produced. He could estimate yardage better than any officer we ever had. Poole had to be on high ground all the time to observe enemy movement. On June 28th his luck ran out and lost his life due to mortar fire. 1st SGT Keith Cormany was also killed. Poole was replaced by Captain Hawkins. (see photo) The Captain was no Lt. Poole, that’s for sure.”

“It didn’t pay to get too close to people. SGT John McGee told me when I visited him after the war that life was never the same for him after I was taken prisoner. As we were saying our last good-byes he laughed and sarcastically said Smith why didn’t you stay in that P.O.W. camp? That was the only time any one had mentioned that I had been a P.O.W. I did not know until that moment anyone else knew except me. Being a P.O.W. is not a great honor, in my opinion. Just another story in the life of a proud 82nd soldier.”

“General Gavin, our last commanding General, said in a book I own: On D-Day, June 6, 1944, the 82nd Airborne Division participated in the initial operations of the invasion of Western Europe (France) for thirty-three continuous days, without relief, and without replacements. The 82nd accomplished every assigned mission on or ahead of the time ordered. No ground gained was ever relinquished and no advance was ever halted by the enemy. The 82nd sustained an aggregate loss of 46% killed, missing in action and evacuated wounded.”

“I know several men with small wounds who refused to be evacuated. They said they would rather stay and fight with their buddies and the medical personnel didn’t give them any argument.”

“All were well aware that every man who could help out in any way was needed if the battle was to be won. I’m proud to have been part of this momentous invasion.”

TANK BATTLE SIDE STORY:

“We had gotten some green men (new recruits) in the 319th just before we left England. They didn’t know sh*t. They were young and just out of basic training. Somehow, one of them got inside the enemy tank we had just blown up with the two dead Germans. The other new recruit was outside. They were trying to get a machine gun out of the tank when the fellow inside accidently fired the gun, hitting the other fellow in the chest. Poor guy never knew what hit him. Sergeant Deloss Richardson said the report was filed as Killed In Action. The one who pulled the trigger was sent back to England. Don’t know what happened to him after that. Sadly, these two men should not have been in that tank in the first place. They had deserted their post and gone into the tank. The rest of us didn’t know it until we heard the shots fired. Sad. I believe this battle took place near the town of La Haye-du-Puits, about 15 miles southewest of Sainte-Mere-Église. Sgt. Tom Sewell was the chief of machine gun section, he was there in a minute and put the shooter under arrest and turned him over to Captain Cargile.” (see above photo)

PAPILLON HALL AND THE LEGEND OF THE GREEN SLIPPERS:

In early April of 1944, the 319th Battalion left Ireland and traveled to Papillon Hall in the town of Market Harborough, England. Market Harborough was a British Royal Air Force station, a place for allied military training, and also where Elden and his fellow glidermen went for training and replacement soldiers.

Papillon Hall itself was a large structure, first built in 1903, that was requisitioned by the army during World War II. It was used as a billet for the 319th Glidermen and the 82nd Airborne Division of the U.S. Army. The building itself was set-out in a butterfly pattern (Papillon means butterfly in French) with four distinct wings.

The soldiers lived in the main building and a cluster of quonset huts. But no space was wasted, soldiers also slept in horse stables and barns.

Papillon Hall - Market Harborough - 1944 - photos courtesy of Steve Hewes

“There were eight men to a room. Ted Zmuda slept on a top bunk. One morning Ted told me the night before he woke up and Corporal Lake was walking around his bunk urinating on the floor. Seems Lake drank a lot, actually you could have put alcohol in gasoline and he would have put it under his belt. After breakfast I told Lake that we knew how the puddles of water were getting there and said, Lake you are going to go and get soapy hot water and mop the floor. He said that he was going to mop up the floor but with me. I told him to go ahead but he was still going to mop the floor with hot soapy water and if he didn’t I was going to turn him in to the Captain. He knew that he could lose his rank so he mopped the floor and that was the last time anyone saw puddles of water on the floor. Lake was a good soldier, just too drunk or lazy to go down the hall to the bathroom. Most troubles are caused by ignorance or misunderstanding. Be careful how you remove either.”

“We lined up in front of this huge building (Papillon Hall) to receive a lecture from Captain Cargile about the dos and don’ts of the place. He also told us about a pair of infamous green slippers and the curse that they carried. Cargile said, you can look, but don’t any of you ever lay a hand on these green slippers.”

“The Green Slippers” - photo courtesy of the Leicestershire County Council

“The so-called green slippers were on display in the Green Room within Papillon Hall. And Captain Cargile had warned us the pair of slippers were not to be touched and had an evil curse on them. We were told the owner of the hall was murdered and was buried just outside the Green Room. During our stay, the Green Room was a place for letter writing, listening to a record player and lots of gambling. There was a grave marker outside, behind a hedge, but we couldn’t read the engraving on the stone through the window. Was it the master of the house, or the lady who had worn the green slippers?”

“Anyway, these green slippers were high up on a wall with the toes pointed down. They were near the ceiling of this Green Room, inside a glass enclosure. And well out of reach of anyone on the floor. Despite this, a private named Ward stole the cursed green slippers sometime in April of 1944. I don’t see how he could have pulled it off alone. He must have had someone helping him. Never found out. Anyway, the missing slippers caused a big stir and resulted in a big investigation that lasted the better part of a full day. They were finally found in Ward’s possession and returned to their glass encasement.”

“The slippers were still in place when we left for Holland later that year, in the fall of 1944. I never entered the Green Room without staring at them. There was something about those slippers that made me want to look. Could it be that the lady who owned the green slippers was buried outside that window? Do you think someone might have stolen them a second time? I love a good mystery, don’t you? If I had known then what I know now I would have been scared to death walking through Papillon Hall at night all by myself, with nothing but a .45 Army pistol and a flashlight. How in the world can you kill a ghost? They are already dead, aren’t they? Now I’m sure I have a guardian angel looking over me. I mean it!”

LATE MAY, 1944 - TWO ENGLISH GIRLS:

TEC 5 James Vineyard

“One day, while we were still stationed at Market Harborough, a PFC friend named James Vineyard who I called “Jimmy Cagney” (he looked like the movie actor Cagney - see photo) and I took a walk toward the village of Foxton. On the way we met two English girls our own age (early 20’s) who agreed to take a walk with us. The four of us agreed to meet again the following Friday night in one of the two pubs in the town of Market Harborough. We kept our date the following Friday. The girl I was with, Miss Edna Norman, was a very pretty girl who traveled by train into town and back home again. Cagney and I walked Edna to the train station that night. It was very dark, and we had some time finding our way. We got Edna on the train and made a date to meet again the very next Friday. This date, however, was not kept. Edna never showed.”

“The station master had come up to me the night we saw Edna off and said, ‘Yank, if I were you, I wouldn’t have anything to do with that girl. She has other Yanks on her list, especially a U.S. Air Force guy that she meets regularly in another town.’ I said to myself then, if that SOB wants her, he can have her, and that was that. The last of Ms. Edna Norman.”

“There was a lot of jealousy between airmen and us regular Army fellows because they had life so much better than we did. Better food, better quarters, more entertainment (movies), a nicer PX, while we had none at all. If some movie star came to entertain the troops, they always went to the airmen. But, after I learned the history of the Air Force, I changed my mind. They deserved all they got. A lot of these good men lost their lives over Germany.”

WHY THE ALLIES WON:

Elden wrote some prophetic words as he compared the U.S. Army to the German army in a letter to his niece and nephew on December 10, 1997.

“The German army was well disciplined. Too well disciplined. It seems to me that the German soldier couldn’t make a decision on his own. He had to get orders from his superiors to do anything. This seemed to carry all the way to Hitler himself. Whereas, the American G.I. was taught to do the job to the best of your ability and as quickly as possible. Then you go from point one to point two using good judgment and make decisions on your own. Not a bad idea. It worked out pretty well, I think. We won the war!

“Is it any wonder the Germans lost the war? There is no doubt about it. We had the best Army, Navy, and Air Force. Around the end of September (1944) the Germans lost control of the sky and never regained it. If the enemy had sent an aircraft our way while we were marching on Naples, I have no doubt the U.S. Air Force would have shot it down. I am proud to have taken part in the invasion of Italy.”

APRIL, 1943 -THE BOAT RIDE FROM NEW YORK AND THE MARCH ACROSS NORTH AFRICA:

Once training in the USA had been completed, Elden Smith and his fellow glidermen left New York City aboard the SS Santa Rosa bound for Casablanca, Morocco, North Africa. “We were in a convoy of ships. Ships everywhere. Our ship changed positions many times. Sometimes we were in the middle, then close to the front, then back at the rear of the convoy. We could see that we were all traveling in a zig-zag formation. The 319th Battalion lived on open decks, no roof over our heads. Water was in short supply. We got two meals a day if you could call them meals. Everything was boiled. We did not have tables, so we had to eat this slop standing up.”

“If you have never taken a shower in cold Atlantic Ocean salt water, I suggest you try it. It’s an experience you will never forget. We had a so-called saltwater soap, but it was more like wagon axle grease. If I could do it all over again I would have taken my clothes off, stood around a while, then put them back on without ever getting wet.”

“We arrived at Casablanca the first week of May 1943. We left by rail for Oujda in western Algeria, and lived in pup tents in a wheat field for intensive training. We were preparing for the invasion of Sicily. We maneuvered across North Africa doing just about everything the higher command could think of to make us miserable. As we made our way across Algeria, we came to a mountain range. Someone thought the best way to get to the other side was by plane. So we loaded all our stuff - a jeep and all our gear - into a C47 transport, the same plane that towed our gliders.”

“We crossed these mountains safely, but it rained before we got to the landing strip near Bizerte, Tunisia. The landing strip had been covered over with clay and the rain had made the clay as slippery as a wet bar of soap. Planes that had landed ahead of us were piled up like a bunch of children’s toys. We hit that clay, slid this way and that, clipped the wings and the fuselage, and finally came to rest by running smack into the side of another downed plane. No man was seriously injured. My Guardian Angel was there working overtime, I’m sure.”

“The invasion of Sicily and Italy is drawing near.”

SEPTEMBER, 1943 - THE INVASION OF ITALY:

“The invasion of Italy took place the first week of September 1943. It was here we changed our method of operation. The allies executed an amphibious landing north of Salerno, taking the Germans completely by surprise. We set foot on shore without even getting our feet wet!”

“There wasn’t a German within several miles of this little Italian village, called Maiori, on the Amalfi coast.”

“They replaced our 75mm howitzers with 105mm howitzers. We only had a few days practice learning to get the 105mm howitzer into position before leaving north Africa on an L.C.T. (Landing Craft Tank - an amphibious assault craft used for landing tanks on beachheads). We got all our 105mm howitzers and jeeps, along with the other equipment on dry land. Then we started up a narrow mountain road. We walked about 6 miles, close to the peak, and got our howitzers into position. We started laying shells on the enemy positions on the other side of the Chiunzi mountain.”

“For 8 continuous days, the Germans tried to come up the other side of mountain through an opening known as the Chiunzi Pass. They never did. Our howitzers kept them off our side of the mountain and we gave them hell in the valley down below.”

The German’s uphill view of the opening to the Chiunzi “88” Pass and narrow road

“The Germans did manage to get one large tank up a narrow road. (see photo) It fired a few rounds then started backing down because there was no place to turn this monster around. The driver got too close to the edge and the tank slid down this mountain for a few hundred feet stopping up against a big bolder. The driver and several men were taken prisoner. They were lucky the tank stayed right side up.”

“Our howitzer will go down in the history books I feel sure of this. When the Germans used their heavy weapons and mortars the shells hit the top and other side of this mountian.” (Chiunzi Pass became more commonly known as the German “88 Pass” as enemy artillerymen hit the pass often with their 88-mm shells.)

“Darby’s Rangers were protecting our perimeter and well entrenched so their losses were almost nil. When the Germans raised their sights the shell went over our heads landing in the valley below or on the mountain behind us.”

“There was a home right in front of our howitzer. The folks had left so no one was there. Captain Cargile said, if any man goes into that home for any reason he had better get my permission first. No one entered that I know of. The only damage we did to the building was a few shingles were blown off by the muzzle blast from our 105 Howitzer, and we had to cut down one fig tree growing in the yard. Also, there was a large church directly behind our position and German shells landed all around this place and not one hit the building. I have a feeling the Priest and the Sister’s prayers were answered.”

Elden Smith’s hand drawn map - illustration of the battle lines on the west coast of Italy (Maiori - Naples) and North Africa

“On our side of this mountain we could see the village of Maiori (see map drawn by Elden Smith) where we came ashore. The Navy had a ship in the Bay of Maiori that fired shells (16 inch so we were told) up this valley. We could hear the shells as they passed over us. We wondered what they were firing at – well when we got to the other side we could see the destruction of a large town at the bottom.”

“The Air Force flew dive bombers up this valley. When we got a fire mission using smoke shells we could always expect these planes to come. The smoke was used to mark certain targets giving our ground troops trouble. We didn’t know what these targets were. I talked to some of the Rangers afterwards and they said the planes dropped bombs and strafed troop movement, tanks, trucks and machine guns. The valley was so full of targets sometimes the forward observer had a hard time deciding which one was the most important. Is it any wonder the Germans lost the war?”

“At the end of September 1943, we finally got marching orders and got to the top of Mt. Chiunzi. The most beautiful sight I’ve ever seen (see photo below) was way down below...the city of Naples, its beautiful harbor and Mount Vesuvius in the distance. We got orders to move towards Naples. By this time, the Italians had thrown in the towel. So it made things a lot easier for the U.S. Army.”

Occupation of Naples:

Elden Smith’s view of the Bay of Naples and Mount Vesuvius from atop the “Chiunzi Pass”

“The 82nd Airborne Division and a branch of the British army took Naples without a lot of trouble. When the Germans retreated they turned raw sewage into the water mains, creating a severe water shortage. They also put bombs in all the major public buildings, set to go off when the Americans turned on the electricity.”

“The 82nd was assigned the task to bring some kind of law and order back to this city. It turned out to be a bigger task than was first anticipated. There was a shortage of everything, food and drinking water was in very short supply. The natives were very restless and weary. They would stand in line for hours for a loaf of bread then find out that there was none left. This caused a lot of fights to breakout. Our orders were to be as polite as possible and stop trouble before it started with the least amount of force. This tactic paid big dividends in the end. I heard many locals comment the Americans are our friends, they are nothing like the Germans. That made me proud to be of some help. We also cleaned up after the main post office blew up. Several people were killed including some American soldiers. This was my first experience dealing with the dead and wounded, and blessedly, my last.”

“Battery “B” took up quarters in a very large estate owned by a Doctor (a German sympathizer) high up on a hill over looking the Bay of Naples. Beautiful in spite of our living conditions. We could expect the Germans to bomb the harbor every night, with the usual flares hanging like Christmas decorations, lighting up the place as bright as day. It was surprising how small the damage was when one considers the number of vessels the Navy had scattered here in this beautiful bay.”

On October 5, 1943, the armies got bogged down near Villa Literno at the Volturno River, an area about 25 miles north of the City of Naples. The 319th was called on once again, this time to secure the bridge head at the Volturno River:

Elden Smith (L) and SGT John McGee - Normandy ‘44

“We were there several days and nights, I don’t recall now how many it was. This was the most miserable few days and nights of my life. After we got into position it started raining. It rained and it rained day and night. Sgt. John T. McGee (see photo) and I stayed in the same fox hole about 100 yards in front of our howitzer. Intelligence reported the Germans were preparing a counter attack and most likely at night. I had doubts about this report then and McGee and I discussed it. We wondered, how in the hell are the Germans going to get across this river when we can’t get to their side? You figure it out. Anyway, the whole battalion had to abandon the Howitzers and take up defensive positions out front each night. Finally, we got a bridge head secured and pulled back to Naples to the same building.”

“The doctor who retreated with the Germans left behind his maid and gardener. They were married and lived in a small house on this estate. The woman and man washed our clothes for almost nothing. They preferred payment in food rather than money. Our motor pool pulled a tank of water and parked it close to their house so they wouldn’t have to carry it so far. I expect the neighbors were jealous of them having so much food and water. Conditions kept getting better as the Navy got more supplies ashore, especially flour. The bread lines got smaller and smaller until there were none at all. Also, the Army got tankers of water scattered all over Naples so the water lines soon gave way to some peace and quiet. Life in general began to slowly return to a more normal condition. It was a pretty good struggle but everyone was better for the experience. The oranges were getting ripe and all of us hated to leave this lovely city but the war is far from being over.”

“If all the generals, presidents and dictators of this world had to personally fight in the wars they managed to start, there would be far fewer wars!”

NOVEMBER 19, 1943 - LEAVING NAPLES, SAILING TO ALGERIA, IRELAND AND ENGLAND:

The 82nd Airborne Division sailed from Naples in November and spent Thanksgiving in Oran, Algeria.

“We had a four hour shore leave in Oran after our Thanksgiving meal. I noticed before I left ship, a contraption of cables hauling something from the top of this very high hill in buckets and loading it into a barge that was docked. I walked up to this opening to see small cars full of iron ore coming out of this mine. The cars dumped the ore into these buckets which in turn went down the steep hill on these cables. The ore was dumped into a barge, then the empty buckets returned to be filled again. I stood in amazement as I watched this series of cables, cars, buckets, and pulleys go through this operation again and again. It appeared to me that the gravity of the full buckets ran the whole operation. I didn’t see an operator anywhere. I never saw anything like this before or since and felt it was well worth my time climbing this hill. I wish I could have entered the mine itself. I then walked around the dock taking a view of this beautiful Mediterranean sea.”

From Algeria the 319th sailed due east towards Gibraltar. This ride was pleasant; good quarters, good food three times a day, and a well-deserved rest:

“The only thing that interrupted our pleasant ride were the commanding officers giving short pep talks telling us what great heroes we were and how bravely we had stood up to the enemy. Before this it was, you are good soldiers, now they are saying what wonderful veterans we have turned out to be. Hell! ….they didn’t have to tell me this I was smart enough to figure that out for myself, so I thought, why don’t you crawl under something and stop disturbing my rest?”

“Before we got to the Straits of Gibraltar we saw our first dolphins, they played around our boat for miles, it looked like they were having the time of their life. It seemed they were swimming effortless on the ships wave. This is something else I have never seen before or since. Going through the straits the ship slowed down so we got a good look at this big rock. That’s about all I remember about the place. But now we are in the Atlantic Ocean, headed for?”

IRELAND:

Through the straights of Gibraltar the 319th finally docked at Belfast, Northern Ireland on December 9, 1943.

“Here we got on trucks and were taken to the town of Ballyscullion. We lived in Quonset huts, had hot showers for the first time since leaving the USA and often got passes into town. Beer was in good supply and the food in the pubs was also good. I fell in love with the people and their lovely country.”

Living conditions were good. “We got passes to town often. Beer (the Irish called it stouts and sitters) was plentiful but I didn’t drink very much. There were lots of stone fences and I noticed gaps here and there in these walls. I wondered why is this?… and was informed it was left open so the Leprechauns could travel back and forth. Every person I spoke to believed in these little elves. They would say, why we wouldn’t dream of shutting them out? These fences were not built to keep livestock in just to pretty the country side an get rid of the stones. A wonderful idea I thought.”

“We spent the winter here and the night before Christmas I went into town to a church Christmas program. Not much different than the ones in the US. A young good looking Irish girl asked if any Americans had a favorite song they wanted to hear. To her surprise they wanted When Irish eyes are smiling. At a Christmas Program I thought, how foolish can you get? She was so kind, though, but had to go home to get the music for her piano player. She was a very good singer and I enjoyed the music.”

Wallace Edwards (L) and Elden Smith - 1984

During training the 319th made several trips to the artillery firing range. “ I saw men and women cutting peet into small pieces to dry and use for fuel. Lots of their buildings were made of stone with thatch roofs. I wished many times that I had been an artist. The image of this in my mind would be nice to have on canvas. Oh! well, dream on Elden.”

“One day I got a letter from a girl I had gone steady with before going into the Army. Our break-up was not a pleasant one. (Now this was the first and only letter I got from her.) Even before I opened the letter I had this strange feeling that something wasn’t right. I thought, why is she writing me? I only remember but one sentence in this letter. She wrote, I’m sorry to hear about your Mother. I started crying and Sgt. Wallace Edwards put his arm around me and said what’s the matter Smith?…. I couldn’t answer him. I just handed him the letter. After reading the letter he commented, all she said is I’m sorry to hear about your mother, now that doesn’t mean she is dead, maybe she is sick or fell and broke a leg, it could mean anything? I knew that mom had passed away. I just somehow knew it. Some two weeks later I got a letter saying amongst other things that mother died, Dec. 26, 1943.”

“Our life soon got back into the same old rut, 5 mile marches about 3 to 4 times a week, guard duty, back to the firing range to waste a lot of 75 mm ammunition. The 105 mm howitzers were taken away. We didn’t know it then but this was our first training for the invasion of France. It is now the beginning of a new year, 1944. The weather was damp, foggy and cold. I got sick here and was isolated from everyone except the medic and Doctor for one week. I had a good case of the Flu, about all I could think of was… Oh no!..I lost a brother to the flu at the end of WWI.”

The 319th Battalion left Ireland in March of 1944 and traveled to Papillon Hall in Market Harborough, England.

SEPTEMBER, 1944 - THE GLIDE INTO HOLLAND AND THE BATTLE OF MARKET GARDEN:

On September 18, 1944, Elden Smith and B-Battery of the 319th departed England from the Fullbeck Airfield on a combat mission. 142 enlisted men and 4 officers glided into Holland with most of their Waco gliders landing 3 miles northwest of Groesbeek. B-Battery landed at 1445 hours, that evening Elden Smith and others were reported missing in action.

“We took the northern route to Nijmegen, Holland, on the Waal River, close to the German border. Ours was an 80-mile journey over enemy territory. The 101st Airborne took the southern route from the same airfield in England. They were over enemy territory some 60 miles. Now the reason for the difference – the 101st flew over Belgium then turned North.

Our glider was loaded with one Jeep and several rounds of 75 mm ammunition. The ammo was tied down behind the Jeep. The driver of this jeep, I believe was ‘Vine’ (James Vineyard) and Ted Zmuda sat in the front of the Jeep. I sat up front with the pilot. His name was Roy B. Martin. His rank was between a Master Sgt. or a 2nd Lt., he had a brown bar on his collar.”

SGT Wallace Edwards

photo courtesy of Cheryl Roser

Regarding the rest of the #1 gun section, “Sgt. Wallace Edwards (see photo) had the 75 mm howitzer and the other 5 men. Sgt. Edwards and I were in #1 section while at Camp Claiborne and never in any other section. Our glider and plane made the English Channel crossing without any mishaps. Everything was smooth until south of Rotterdam, there we ran into some very heavy anti-air craft fire. The shells were bursting all around, finally a shell hit the right motor of the C47 pulling our glider. The tow rope that connected us was severed and we were on our own. This was the most sinking feeling I have ever had in my entire life. As you know we flew close to the ground so in less time than it takes to tell the story we were on the ground.”

THE LANDING:

“We landed in a plowed sandy field near a canal. The glider had plowed into the soft earth and the nose of the plane was torn to bits. But we just walked out. We were very fortunate! The jeep and ammunition had stayed in place and the four of us glidermen didn’t get a scratch. When we hit the ground, the glider stood on its nose for a short while, we felt sure it was going to flip on its back. But it didn’t. God was with us for sure!”

“There was a church with a tall steeple nearby and the Germans had a machine gun nest in it. This gun kept us pinned down, with no escape route, until the Germans got some men (about 20 or so) down the canal. It was either get killed or give ourselves up. Of course, we gave up.”

SEPTEMBER 1944 - GERMAN P.O.W. CAMP:

“The Germans marched us to Rotterdam and from there to Amsterdam, from which we headed east. As we marched through Amsterdam on a warm, sunny October day, sirens were screaming, and German SS troops were shooting at anyone who tried to sneak a peek at us - the first P.O.W.’s to enter their beautiful city.”

“I saw one man fall. He was peeking around a building and an SS trooper dropped to one knee, took aim, and fired one shot. The dutchman fell forward, dead. Just because he wanted to see the soldiers who were in his country fighting for his freedom. At night the Germans put us (and about 100 British P.O.W.’s) in this large, empty building that was so close to the action we could hear the artillery fire all night.”

Elden Smith’s German P.O.W tag -75042

“The next day we marched all day and spent the night in a railroad depot. From there, we were taken by train to a P.O.W. camp in Germany, called Stalag 3C (this camp was part of a larger prisoner-of-war facility known as Stalag XII A) about 50 miles east of Berlin, near a town called Küstriner on the Oder River. One side of the river was Germany, the other side was Poland.”

“At Stalag 3C there were 2,000 of us, housed in barracks with 3 rooms, a small window in each room, the walls were very thin and we had no heat. There were 33 men in two rooms and 34 men in one room. I happen to be in the middle room that had 33 men. On one side was a long wooden shelf with eight straw mattresses and below this on the floor were eight more straw mattresses. In the middle a 10-foot-wide space with a table and two benches to sit on. The only entertainment we had was playing cards. The other side of this room was the same as the first except one shelf had 9 mattresses. I slept on the floor with 7 other men. Each room had one door opening.”

“We had one Master Sgt. (American) over one compound. There were two compounds with 1,000 men in each. There was a double barbwire fence with a 24-hour guard walking in between. The fence was about 15 feet high and it was buried in the ground some 5 or 6 feet. There was this kind of fence around the whole Stalag 3C with a guard tower on each corner, two armed guards with a machine gun mounted in the middle of this tower stood watch 24 hours a day. Each tower had one search light. (The guards used them quiet freely). If one stepped out at night to use the toilet the light never left you until you entered the barracks again. While on the subject of toilets, each compound had just one each. It was a building about 30’ x 12’ with something like 20 to 25 holes. The waste dropped down into a cement pit, which a Russian prisoner flooded with water, stirred it with a long pole then pumped it out with a hand pump into a tank mounted on a wagon and pulled it away by hand. One day there was a lot of excitement going on while the prisoners were pumping out the pit. They had found a body without dog tags or other identification. I suspect he was murdered.”

Hand drawn map - illustration of Stalag 3C by Elden Smith - courtesy of Carma Cupp family

“I arrived the latter part of October or early November, 1944 and Master Sgt. Thomas was over our compound. He was in charge and reported to the German Sgt. (which we called porky because of his shape and size). He wasn’t a bad fellow. His ideas and actions were fair to good. Each room had one sergeant who reported to a Master Sgt Thomas. (The Germans said that our Stalag was the best organized and gave them the least amount of trouble than any other Stalag). For the most part we were older soldiers and had better training than most prisoners.”

“We had two sergeants from Kentucky, 1st Sgt. Webb and a Sgt. Harris. One day Webb reported to us that some of the prisoners were going through the chow line twice. Chow consisted of one bowl of thin long stringy meat with some grain once a day. Sgt. Webb suggested someone be appointed from each barracks to stand guard and see that no one went through the chow line twice. He appointed himself. I told Sgt. James that I didn’t trust that s.o.b. at all. Sgt. James agreed, we also felt the same way about Sgt. Harris. He and Webb stuck together like glue. I told Sgt. James that I was going to keep an eye on Webb. Sgt. James cautioned me not to turn my back on Harris.”

“Sgt. James caught malaria fever in Africa and it came back to haunt him. He was very sick but always made it to the chow line and back. He and I slept side by side. He was one swell guy and we liked each other better than brothers. He would drink some soup then give me the rest. This went on for some time. I feared for his life but he pulled through. His skin was yellow and the whites of his eyes.”

“The next day Webb went through the line first, got his bowl of soup then stood beside the gate and hurriedly ate the soup. Then, he went back through the line again. He didn’t see me because I had mingled in with the second bunch of men about 20 feet behind the first bunch. I went back to the barracks and said nothing to anyone except Sgt. James. He wanted to know what I was going to do about it?”

“Sgt. Webb did the same thing again the next day. When I got back to the barracks I confronted him. No one thought I was lying except Webb, of course, he denied doing such a thing. And wanted to know what I was going to do about it. My idea was to find another guard, one we could trust. Webb and Sgt. Harris were as mad as two old setting hens, but we elected another Sergeant, one that everyone could trust.”

“The next day Harris picked a fight by bumping into me twice and said sorry Mr. Airborne man. He invited me outside for a fight. Now there was a spot behind our barracks where none of the German guards (not even the search light shined on this spot) could see us. We had an escape committee, it was they who had found this spot. I believe then as I do now the Germans wouldn’t have given a damn if we had killed each other. Listening to Harris and I was this red headed sergeant who was a friend. He once jokingly said I reminded him of his sister who had wavy hair! Sgt. Harris’ challenge to fight was completely unexpected by me or any other one else for that matter. So Im thinking if I go out that door Sgt. Harris is going to beat the living hell out of me, but I’ve got to stand my ground and not be thought of as a coward. Before I could say a word the red headed Sergeant said, ‘Harris, before you whip Smitty you’re going to have to go through me first, you big cowardly son of a bitch let’s go outside,’ and they did. It was over in about 5 minutes. The red headed sergeant walked in without a mark and said, ‘the last time I saw the son of a bitch (Harris) he was laying back there in the snow bleeding, I could have killed the bastard but I felt sorry for the son of a bitch.’ Harris came back in shortly with a badly cut upper lip and a cut above one eye. The red head said, ‘Let that be a lesson to you and if you ever cross Smitty’s path again I’ll kill you!’ From then on I never spoke to Sgt. Harris again.

Do I have a guardian, YES! I believe I do.

“Sgt Harris had been in trouble twice before. He had stolen some raisins from another man and his punishment was 32 of us got one whack at his rear end with a belt. You see the Red Cross sent raisins and pieces of cheese about 1 inch square and about 3 inches long. Of course Sgt. Harris bit another man’s cheese in half, then denied doing so. The three sergeants from our barracks along with Sgt. Thomas and Sgt. Porky had a trial. They made Harris bite the other end of the cheese then compared the teeth marks. Guilty as charged, Harris was sentenced to stand in one spot and hang on to the fence for 2 hours in the freezing cold. He never stole any more food. All 2,000 of us prisoners were supposed to be non-commission officers, but everyone had doubts about Harris. He didn’t have brains enough to pour water out of a boot with the directions written on the heel.”

MY LAST DAYS OF CAPTIVITY:

“Stalag 3C had large mounds of earth (there were three of them) about 25 to 30 feet high and 60 feet or more across the bottom, from my farm experience I expected they contained potatoes. A few days before we heard the Russians were coming the Germans opened one of these mounds. There were potatoes and and the non-American prisoners began loading them on to trucks with trailers behind each truck. Both of which had open tops and a German guard on each. On our way to chow one day some of the prisoners began stuffing their pockets with these potatoes. The guards got very excited but kept their cool and did not fire their weapons. Then, one poor guy slipped and fell while walking backwards between the truck and potato trailer. The trailer ran over his head, it was as flat as the piece of paper I’m writing on now. This poor guy wasn’t dead for a minute when someone took his shoes and potatoes. They held a short service and at the grave site the Germans presented an American flag. Boy, that was one of my proudest moments, just think, an American Flag flying on German soil and the war wasn’t over yet.”

“Things got quite exciting when the Germans began bombing everything that moved on this black top road running south by the camp, but not one bomb or bullet hit inside the compound. I wondered what the German pilots thought when they saw our American Flag? For the most part I felt the Germans kept a cool head. The worse treatment we got was lack of food, medical attention, no heat and standing outside for roll call regardless of the weather conditions. Everybody had to be accounted for if it took 15 minutes or 2 hours. It made no difference to Sgt. Porky, he wasn’t going anywhere. It did get miserable at times, roll call was every morning. By the way, the Germans got only one mound of potatoes hauled away, the other two mounds would feed the oncoming Russians.”

RUSSIANS DRIVE GERMANS FROM P.O.W. CAMP:

“Several days before January 28, 1945, we could hear artillery and tank fire in the east so we knew without a doubt that the Russians were coming. So I went to check the time on my wrist watch, I wore it on my ankle so the Germans wouldn’t steal it. Then realized I had lost it, the old watch band got brittle and broke. It was gone, what a loss!

“On the morning of January 28, 1945, the German guards tried to march us out of our barracks. The Russians were closing in. As soon as the Germans would empty one barracks and get the prisoners outdoors, the first group would go back inside. We kept this up until about noon.”

“Finally, the Germans got really impatient and brought in two trucks full of S.S. troops. The first thing they did was yell, in English, if you don’t march we will kill all of you. They put a sergeant up against one of the barracks and did just that. So...we marched.”

“We were marching four abreast down a blacktop road that ran south from the camp. I was in the rear. Well, all of a sudden, all hell broke loose at the front of the column. Suddenly, everyone was yelling “Go back! Go back! The Russians had cut off the road, killing and wounding several Americans and some German guards. We retreated but the German soldiers didn’t give up so easily. They tried to march us out again.”

“This time, I was one of the guys in front. I thought, now I’ll probably lose my life, and for what? Marching in snow up to my knees I heard a tank fire. I looked to my right and saw three Russian tanks coming toward us firing their big guns.”

“By now the Russians had figured out they were mistakenly firing on Americans. They thought we were Hungarian partisans fighting with the Germans. I started yelling to everyone, go back, go back! And we did. At this point, a red-headed German guard pointed his gun at me and said, very loudly, Raus, which means get out! He wanted me to keep marching with him, as his prisoner. These were my exact words back to him: You go straight to hell, you red-headed son-of-a-bitch! I don’t believe you have the guts to shoot me in the back. And I just walked away. I must have been right because I’m still here today. I stayed two more nights at the camp.”

“Our town was first to fall into Russian hands when they made a bridgehead just five miles south of the town. The Russian army moved so fast from Warsaw to this German border town, the Germans abandoned the area and our camp quickly fell into Russian hands.”

“Do I believe in guardian angels? I sure do!”

THE RUSSIANS CAPTURE BERLIN:

After the Russians crossed the Oder River, heading west, they pushed on towards Berlin. But before they could attack Berlin they had to take some high ground near Küstriner before their final thrust into the German capitol.

“The Russians turned on 140 giant searchlights, trying to blind the Germans. What followed was the greatest artillery bombardment ever mounted on the Eastern Front. Some 10,000 guns of all calibers, plus mortars, tanks, rocket launchers, light and heavy artillery. The eruption was so terrible that entire villages collapsed, huge blocks of cement fell, girders and trees were tossed in the air like matchsticks. An atmospheric disturbance was created, and forest fires blazed as hot winds roared between the trees.”

“The bombardment lasted 35 minutes. It was so intense that men shook and were deafened for quite some time. Then the shelling stopped and the Russians moved forward with their ground attack. The Russians vastly outnumbered the Germans. So the Russian army was never stopped again. They took Berlin on May 2, 1945.”

“The Russians shelled Berlin with over 15,000 rounds of artillery fire. From April 16 until May 2 (1945) the German casualties were 200,000 dead, while the Russian army lost 150,000 men. The Russians marched 91,000 German prisoners through Stalingrad just for a show and of that only 5,000 prisoners lived to see Berlin again.”

FINDING OUR WAY BACK TO FREEDOM:

“At first there was plenty of food, but it disappeared in a few days. The Russians then told us we were on our own. So four of us took off in an easterly direction for Warsaw. We followed the Russian supply lines. We slept in farmhouses and ate what we could find, each day trying to continue on. One evening just before dark, we decided to find shelter. In the middle of a road, in front of his farmhouse, an old Polish gentleman had been shot behind the ear. His arms were stretched skyward, as though he was reaching up for something. He had a wagon wheel rim over his chest and under his legs. He was dressed in night clothes, which meant he’d been running for his life.”

“We went into the farmhouse and found four bodies (men and women) hanging on a door with ropes around their necks. I went into the kitchen to look for firewood and I stepped on something soft. It was a woman’s stomach. She too had been shot behind the ear.”

“There was a cow in the barn that kept bawling and bawling. Sergeant James and I went out to the barn and on the way, we found three more bodies in a small shed. They too had been shot behind the ear.”

“The reason the cow had been putting up such a fuss was that she hadn’t been milked for some time. She was fit to burst. After we milked the cow, she seemed content and quieted down. We fed her and gave her water. In return, we had fresh milk for supper. We mixed it with plain flour and a little sugar and fried this sweet bread mixture in lard over a wood stove. The sergeant milked, fed and watered the cow again. The next morning we were on our way toward Warsaw, to this day I wonder what happened to that poor animal. I despise some of these memories, yet love others such as the Italian people. They were so nice to us, because we gave them their freedom back. God Bless America.”

“We continued to find dead bodies as we made our way to Warsaw. That city was in total ruin in every direction. There wasn’t one building that wasn’t either bombed to ruination or burned to the ground. The dead were in piles out in the fields and at first looked like cord wood because they were covered with a foot or more of snow and frozen stiff. At least there wasn’t any stink. Berlin was just as bad."

“Before we got to Warsaw, we ran across an empty freight train that was heading east and we could ride part way to the Polish capitol. It was raining, and we were wet, cold, and hungry. A railroad employee tried to get us into a box car that had a bed of straw, several refugees, and some P.O.W. American pilots. The pilots were commissioned officers and the four of us gunners were non-commissioned officers. They would not let us in the rail card. The pilots accused us of lying to the railroad man, telling him that we were also commissioned officers. Being called liars did not sit well with any of us and we sure didn’t appreciate them pulling rank on us either. Not here. Not now! A few heated words were exchanged and things were about to get even hotter. The four of us called them every name and dirty thing we could think of, even inviting them to come out and fight like men not like the cowards we knew they were, standing behind their precious gold and silver bars. I still believe today that the four of us could have removed those damn ‘shavetails’ bodily. But discretion being the better part of valor, we accepted defeat and the four of us went back to another, roofless, railroad car. And we were to meet again before we got to Warsaw.”

HORSE MEAT AND A COMMUNIST SPY:

“We got on a passenger train. Stepping into the car, guess who was there? Yep! These same pilots who thought it below their dignity to be caught in the company of enlisted men. And, there just happened to be a very good looking, young, well-dressed women on this dirty old run down car. I thought, that person is out of place. She is just too clean to be among dirty refugees like us and others. It wasn’t long until she started to flirt with this 2nd Lt. that I had words with at the box car incident. She managed to lure him off to a seat by themselves. There was an Air Force Chaplain in the bunch so I moved beside him and sat down. I said Captain Sir doesn’t that officer son of a bitch know that woman is a communist spy? The captain replied he knew what to do.”

“We left the train before we got to Warsaw and some Polish woman took us to a farm house. All of us Americans were put in one large room which had straw on the floor and a blanket for each of us. We had horse meat and dark bread for supper. It was a refreshing meal I must say. But there in the corner was this same 2nd Lt. and his faithful (female) companion “Tonto” all snuggled up. They saw us and were trying their best to act as it they weren’t noticed. But surprise! There was a knock at the door, a woman speaking either Polish or Russian called for this woman. She went outside then came back and said in perfect English to Mr. Lt., ‘ I have to go but I’ll be back in a few minutes.’ She never came back, good riddance to bad rubbish.”

“Now I had my say again to Mr. 90-day wonder. I told him if he wanted to whip me he had to whip all four of us because we were itching for a fight. I asked him his name but he wouldn’t say, so I told him that he had spilled his damn guts to a communist spy! That he should be shot and if the opportunity came my way I would do it myself. He could not defend himself, he knew that he had made a fool of himself so he said very little. Boy did I feel the power that I had over this man! But you know war is Hell. It will cause one (it did me anyway) to do and say things you would never do otherwise. I deeply regret a lot of things I said and did while in the Army and for a short time afterward.”

“When we left the farm house the next morning, all of us Americans were in an open Russian Studebaker truck and traveled all the way from west to east through Warsaw. That’s why I had such a clear description of the city. I sat beside the Air Force Chaplain to be sure I knew him well enough and learn his name so if and when I got back to the USA, I could report Mr. 90- day wonder with the Chaplain as a witness. Did I report? You bet your bottom dollar I did.”

OUR FIRST DAY IN WARSAW:

“The driver put us off on the east side of Warsaw near a river on a very busy street. Again the Russian military kept up a steady pace going west towards Kustrine. We spoke to some English speaking Polish officers who said, ‘we are thankful for our freedom but we wish it had been the Americans who gave it back to us.’ They had no advice for us but some Russians soldiers told us to go to Moscow.”

“On our first night in Warsaw, we didn’t have a place to stay. And it was getting dark. Several polish people showed up and said to a Polish army officer that they could take us into their home. Sadly, in the middle of the night, Russian soldiers burst through the front door, asking for some man. Then they put the poor homeowner under arrest and took him away. This is when I found out that this family had given us their beds and were themselves sleeping on the floor.”

“Are there Guardian Angels? You bet there are!”

“The Polish wife left that night to find out what had happened to her husband. Did we sleep any more that night? No we did not. Here we are two Americans in some strangers home not knowing what has taken place nor what will happen next. Oddly enough, the pilot and I got acquainted fast. Both of us eventually apologized for our misdeeds in the box car. The wife didn’t get back home until daylight. She said her man had been arrested because he had a German name. She was heartbroken. Did this poor guy end up in some labor camp? My guess is he did, that’s the way the communist operate. This was very sad, I shed tears over the arrest of this poor fellow. So, we thanked the woman and left to join our fellow Americans.”

“About noon the four of us heard there was a very large brick house across the river where the refuges coming and going could stay for a night and get some food. We crossed the river on the ice. It was about 150 feet wide where we made our crossing. Upon arrival at this big brick house the folks in charge found out that we were Americans, they took us up to the third floor. We were put in a large room that had lots and lots of straw on the floor. We were given one blanket and with the straw that was enough. It was cold, freezing cold with a lot of snow on the ground. I mention the cold because the bathroom as we say in America was about a 20 acre open field behind this house. The refuges, men, women, boys and girls all used the same 20-acre rest room. It was impossible to step anywhere without stepping on a pile of frozen human waste. One good thing about the cold, there wasn’t any smell. Now do you understand war is Hell. What on earth do all those refuges in Africa do in this type of a situation? Is it any wonder that so many die? I told you this story to get you to thinking about all the people in this world without sewers and clean water. I pity those who are forced to live under such conditions. Are there Angels walking among us? Here is a story that proves to me that I met face to face with my guardian Angel.”

“One day, while us four glidermen were laying in our straw beds in a big brick house on the eastern side of Warsaw, company came knocking. Three Russian soldiers asked us, in English, if we would unload some barley grain down in the kitchen. The grain was used to make soup, which is mostly what the refugees ate. We were happy to oblige. We went to the kitchen and had the 75-pound bags of grain about halfway unloaded when a British private entered the room. The private had a shortwave radio, which he set down on the pile of canvas grain sacks. The voice from the radio had a British accent and it said, ‘This is BBC News reporting to you from London. The port of Odessa on the Black Sea is now open for allied shipments.’ The announcer went on to report other aspects of the war. I remember him saying that the Russians were stalled after crossing the River Oder at Kustrine. Without anyone saying one word the British private picked up the radio and squeezed back out the door.”

“Someone said, ‘that was an English solider.’ The four of us hurried out of the building but the English soldier had vanished into thin air. There were not any buildings, cars, trucks, tanks, trees or any other thing close enough for him to get in, behind or under in such a short period of time. We were left scratching our heads, wondering where he had gone and saying to each other, why didn’t this soldier say something, and why were we so dumb? Where did he go? We also wondered why a British Soldier of any rank would be in Warsaw? He was the only soldier we saw outside of the Americans, Polish, Russians and Germans in that part of the world at that time. It was something we discussed for several days as we started out for Odessa.”

ODESSA:

“From Warsaw sailing to Odessa (The Black Sea) was kind of routine. The Russian soldiers found us rides on trains going that way and fed us for the most part. They seemed to have a knack for finding box cars with straw and other refuges. When we arrived at Odessa the four of us were arrested and put in a building with a high stone wall guarded by Russians soldiers. We were not alone as several other people were in the same building. We had plenty to eat and our first bath in months. And we got to launder our clothes. We also were given a pretty good medical examination.”

“I kept a diary of dates, places and events from the time I arrived at Stalag 3C until I got to Naples, Italy. The Russians looked it over, the Americans at Port Said, Egypt looked it over as well. They gave it back but when I got to Naples, Italy, I was ordered to turn it in at the orderly room. I first refused to do so but Captain Jonnie W. Calton told me I would be court marshaled if I didn’t turn it over. I wasn’t the only one that had their diaries taken away. We were told over and over again and again that it was against Army regulations for anyone to keep a diary. Why didn’t someone at Port Said confiscate it? When we left there I thought I was getting away with something and I almost did.”

“After about 5 days in Odessa, a U.S. Air Force officer (Major Paul S. Hall) arrived out of nowhere. He interrogated the four of us separately. We had to tell all we could remember about our service record...dates, places, names, ranks, serial numbers. Major Hall said the Russians wouldn’t release us until he could prove to them that we were truly American P.O.W.’s, and not Germans or German sympathizers. I guess my interview was convincing, because the major came back shortly and said that I was being released and could make my way down to Odessa and jump on the very first English boat that left that Black Sea port.”

“Our trip from Odessa to Port Said, Egypt was pleasant and uneventful. From Egypt, we sailed into the Mediterranean Sea, up into the Sea of Marmara and from there on to Constantinople, (now Istanbul) the Turkish capital. But we weren’t allowed to disembark.”

“The American Air Force pilots we left on the east side of Warsaw, we never met them again. But while being interrogated at Port Said, Egypt I was asked if I knew anyone that had cooperated with the enemy. I told the officer about the woman on the passenger car and the incident in the house. I also gave him the Chaplain’s name and rank. He assured me that the matter would be investigated. Was it investigated? I doubt it because history proves the Americans considered the Russians our allies at this time and for a long time afterwards. What stupid idiots our intelligent agents turned out to be. I was told not to be critical about our allies, so from then on I kept my mouth shut.”

PORT SAID, EGYPT:

“When we got off the boat in Port Said, we were put on trucks and taken out to the desert. DDT “dust” was sprayed on our heads, up our sleeves, up our pant legs and down our waistlines. We had body lice and we were being de-loused. We walked about a hundred yards further and stripped off all our clothes, including shoes and socks. The clothes were then set on fire and burned to a crisp. Then we walked another hundred yards to some portable showers. We were told to use plenty of soap and the hottest water we could stand. Then we walked another hundred yards and were given new clothes to wear, along with extra clothing, an extra pair of shoes, toiletry articles, pencils, paper, and a duffel bag. That was the end of our body lice.

LATE JANUARY, 1945 - FREE AT LAST

(Elden Smith was liberated from the P.O.W. camp on January 28, 1945, months before the war officially ended.)

“It was late January 1945 and it took me and three other allied soldiers 34 days to get from Stalag 3C to Odessa, (Ukraine) on the Black Sea. We left Odessa on the first British boat to leave their harbor and finally got back into American hands in Alexandria, Egypt. I begged to be sent back to B-Battery (of the 319th) but my superiors wouldn’t hear of it. They said I could possibly give away some military secrets. That was possibly correct.”

“I got on a boat and went from Alexandria to Naples, Italy. I was there for several days. I went back to the building we lived in (1943) and visited some old friends. It was wonderful, they were so glad to see me and had wondered many times what had happened to me. I left Naples by boat and sailed for New York city with about 250 P.O.W.’s on this ship. We were the first to arrive from Europe. Then by rail to Boston, remember the war wasn’t over in Europe at this time.

“I was setting in a theater in Boston, the movie was stopped and we learned President Roosevelt was dead, April 12, 1945. The theater was silent for several minutes until the people could recover from the shock. Got my back pay. I spent two weeks in a hotel on the beach in Miami, Florida and was waited on hand and foot for two weeks.”

FORT SILL, OKLAHOMA:

Private Ted Zmuda

“I took a train and reported to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for more field artillery school training. I got to be Gunner on one of those 240 mm howitzers, one day a week and the other four days on a 105 mm. Yes, the 240mm will fire 18 miles and more. We were in a Field Artillery School training forward observers, good job, I enjoyed it there.”

“While at Fort Sill I was standing in line at the movie theater one day, looking up ahead I saw a tall soldier with an 82nd Airborne shoulder patch. I thought that looks like Private Zmuda! (see photo) I walked up and sure enough it was him. Zmuda was one of the soldiers in the glider with me in Holland. There were four of us in the glider and all were taken prisoner. We had a long visit after the show. He said that he worked on a farm in Germany while a P.O.W. and was treated good, liked the family he worked for and got plenty to eat. He said he had his own room in this family’s home. Zmuda was a good guy. He went to Catholic Mass every Sunday when he wasn’t on duty. I can see why this family put a lot of trust in him.”

“Then the Atomic Bomb. I was discharged Sept. 28, 1945”

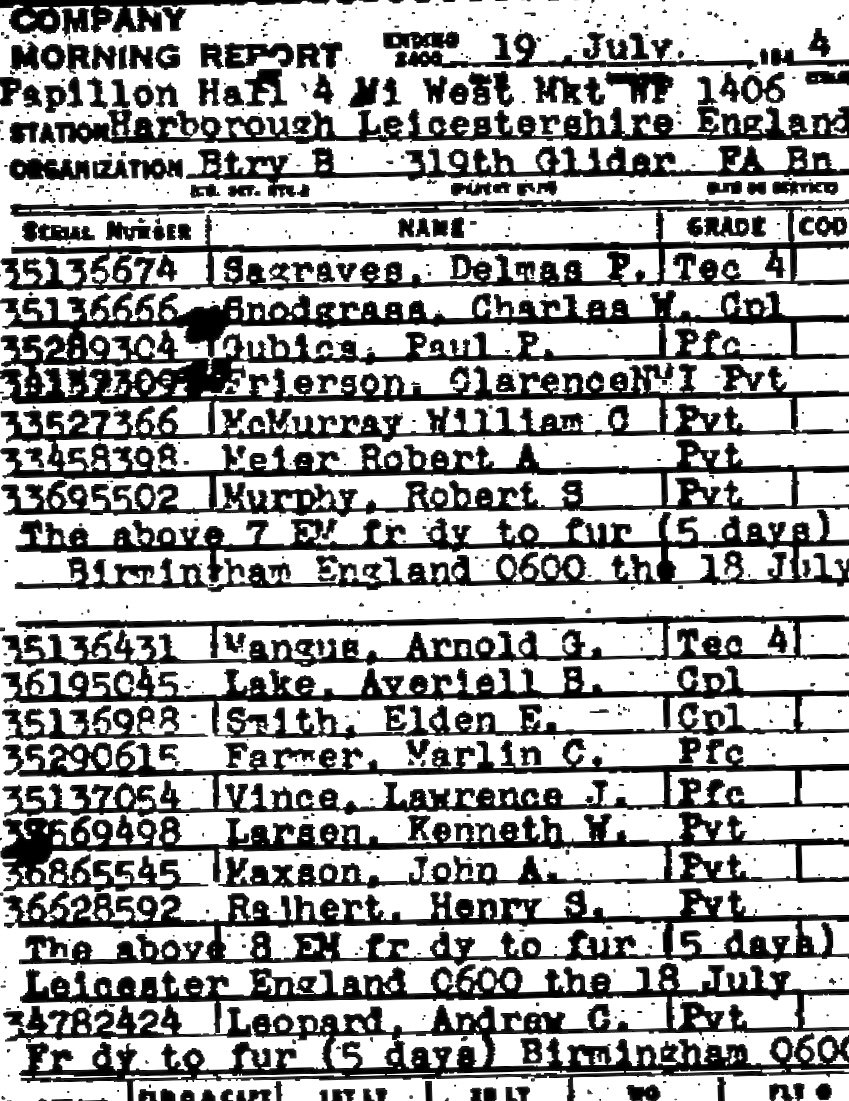

Company Morning Reports

“Company Morning Reports” (CMR) were produced every morning by the individual Army units to record personnel matters. The following events (see below) were reported for Elden Smith:

July 19, 1944 from duty to furlough (5 days) Birmingham, England.

July 23, 1944, furlough to duty.

September 18, 1944, CPL Elden Smith was reported missing in action/combat following the glide into Operation Holland.

Photo courtesy of Carma Cup family

CPL Elden Smith fought in four (4) battles and campaigns; Sicilian, Naples-Foggia, Normandy and Operation Holland.

He was awarded 4 Bronze Battle Stars, Bronze Arrowhead, Good Conduct Medal, Prisoner of War Medal, Presidential Unit Citation Badge, Victory Ribbon and the European-African-Middle Eastern Theatre Ribbon.

Elden Smith told his nephew Bill and his niece Jacky that he wanted nothing more than for people to read his World War II diary and learn what he had gone through.

Elden Smith, 91, died May 9, 2012. Rest in peace, Elden. We will read and re-read your story.

God Bless this soldier.

Elden Smith letters and images courtesy of the Carma Cupp Family

STL Archive Records