Theodore Zmuda

ASN:36629026

Theodore “Ted” Zmuda

Theodore Stanley Zmuda registered for the draft on June 27, 1942. Born February 10, 1922, he was from Chicago, Illinois. His place of employment was A.B. Dick and Company. This twenty-year-old was 5-10, 152 pounds with a light complexion, blue eyes and blonde hair. No obvious physical characteristics were listed on his registration card.

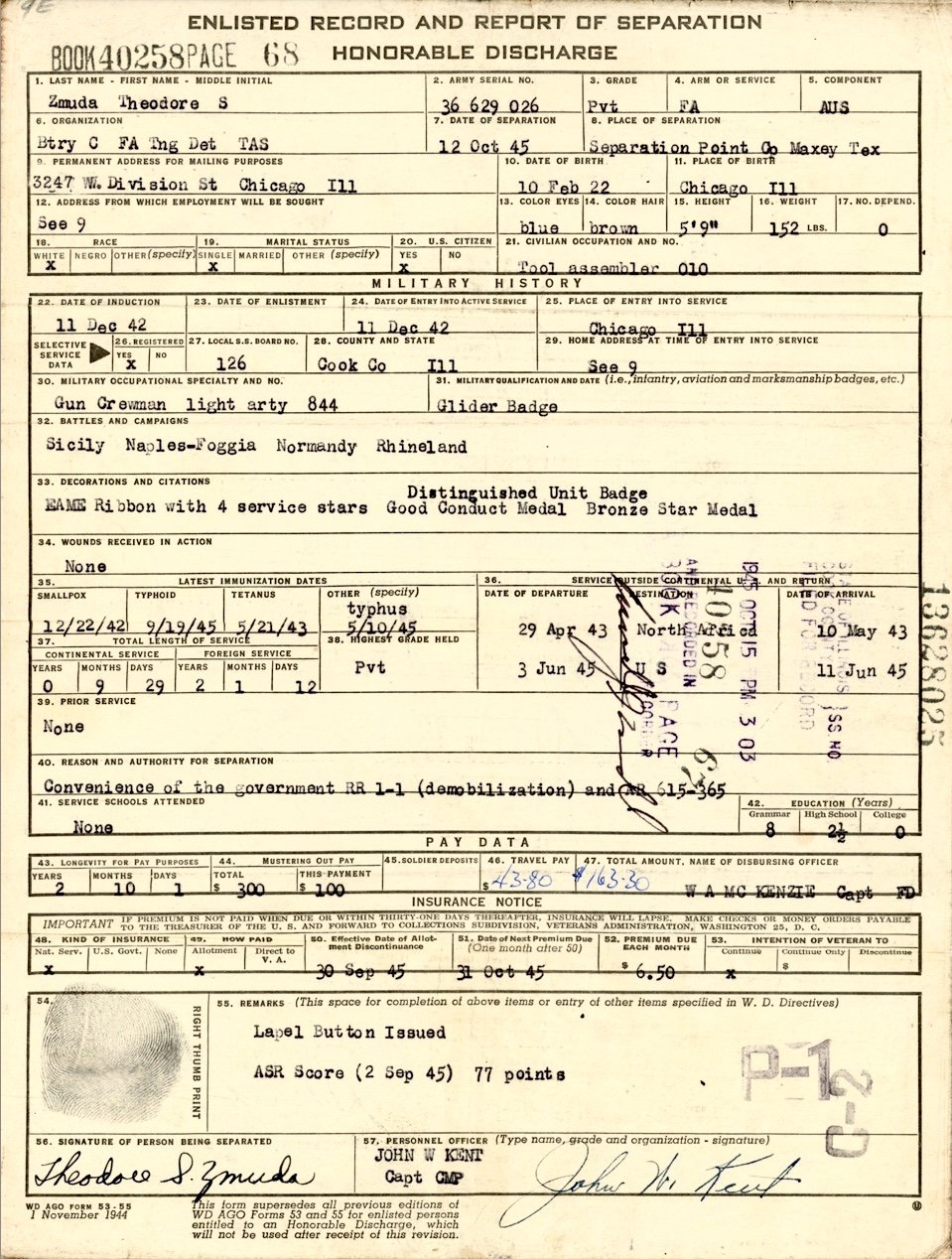

Enlisted in the Army on December 11, 1942, in Chicago, Illinois Private Zmuda received his training at Fort Bragg, North Carolina and later assigned to the B-Battery, 319th Field Artillery Group, 82nd Airborne Division.

Along with fellow glidermen, Private Zmuda traveled to North Africa in May, 1943. He fought in four (4) battles and campaigns; Sicilian, Naples-Foggia, D-Day Normandy and Operation Holland.

Ted Zmuda served with the 319th Glider Field Artillery, B-Battery of the 82nd Airborne Division. Starting in the Spring of 1943, Ted saw action across many battlefields; in Italy at the “Chiunzi Pass,” and Volturno River, D-Day - Normandy and Operation Holland.

While fighting in the “Chiunzi Pass,” Section Chief Milton Chadwick reported that Zmuda broke his ankle while moving the howitzers.

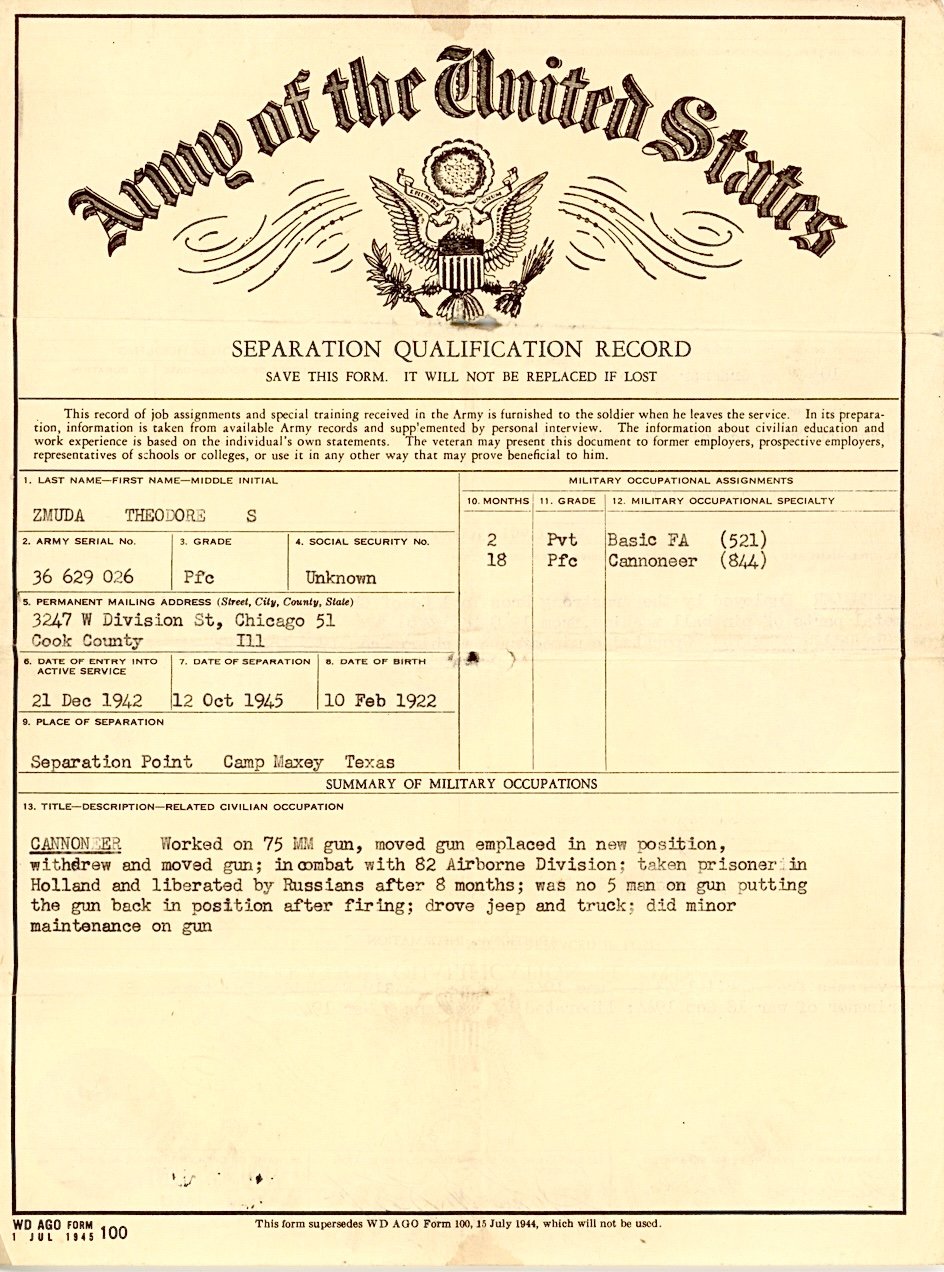

During Operation Holland he and the men from his glider landing were captured. They were imprisoned in a German POW camp but fortunately, Private Zmuda survived it all, returned to the USA, and lived to a ripe old age.

D-Day - Normandy

At 2037 hours of June 6, 1944, Ted Zmuda and B-Battery of the 319th Field Artillery Battalion departed the Membury airfield in southern England. Their Horsa gliders were towed 150 miles into Normandy, in northern France as part of Mission Elmira. Crossing over Utah Beach they glided behind enemy lines and landed two miles east of the town of Sainte-Mere-Église just before 11pm local time. Zmuda survived the landing and fought with his unit for the entire campaign, returning to England on July 13, 1944.

The following photos, (courtesy of Laura F. and Allen Stabenow) depict Private Ted Zmuda, fellow soldiers, and battle scenes from the Normandy campaign.

Market Harborough - Papillon Hall

In early April of 1944, the 319th Glider Field Artillery left Ireland and traveled to Papillon Hall in the town of Market Harborough, England. Market Harborough was a British Royal Air Force station, a place for allied military training, and also where Ted Zmuda and his fellow glidermen went for training and replacement soldiers.

Following the Normandy campaign, the 319th returned to Papillon Hall for replacement soldiers and billeted there through September 1944, in preparation for Operation Holland.

Papillon Hall itself was a large structure, first built in 1903, that was requisitioned by the army during World War II. The building itself was set-out in a butterfly pattern (Papillon means butterfly in French) with four distinct wings.

Private Zmuda lived in a cluster of Quonset huts. Other soldiers lived in the main building, horse stables and barns. No space was wasted.

The following photos, (courtesy of Laura F.) depict Private Zmuda, fellow soldiers and Papillon Hall.

Operation Holland

On September 18 of 1944, Ted Zmuda, Elden Smith, James Vineyard, and glider pilot Roy B. Martin glided into Holland with the 319th Glider Field Artillery. Operation Holland, designed as one of the largest Allied military operations of the entire war, endeavored to create a 64 mile “bulge” into German territory with bridgeheads over the Rhine, Maas, and Waal Rivers. This would allow the Allies to outflank the heavy German defenses of the Siegfried Line and enable a swift entry into Berlin.

Departing the Fulbeck Airfield in England, they were towed in a Waco Glider transporting a Jeep and 75mm howitzer ammunition. The towing C-47 lost its right engine to enemy flak forcing an untimely release of their glider. Already flying low the glider crash landed moments later in enemy territory.

Private Zmuda and the other men were uninjured but came under immediate attack by enemy machine gun fire and over 20 enemy infantry. With a choice to fight with no cover and die, or surrender, they chose the latter. Zmuda remained a prisoner for the duration of the war. He and Elden Smith (another B-Battery soldier whose story we document here) were sent to different POW camps.

POWs from Operation Market Garden were moved on foot, by motor convoy and train to various locations, initially in or near the city of Amsterdam, and from there dispersed to various POW camps, or Stalags.

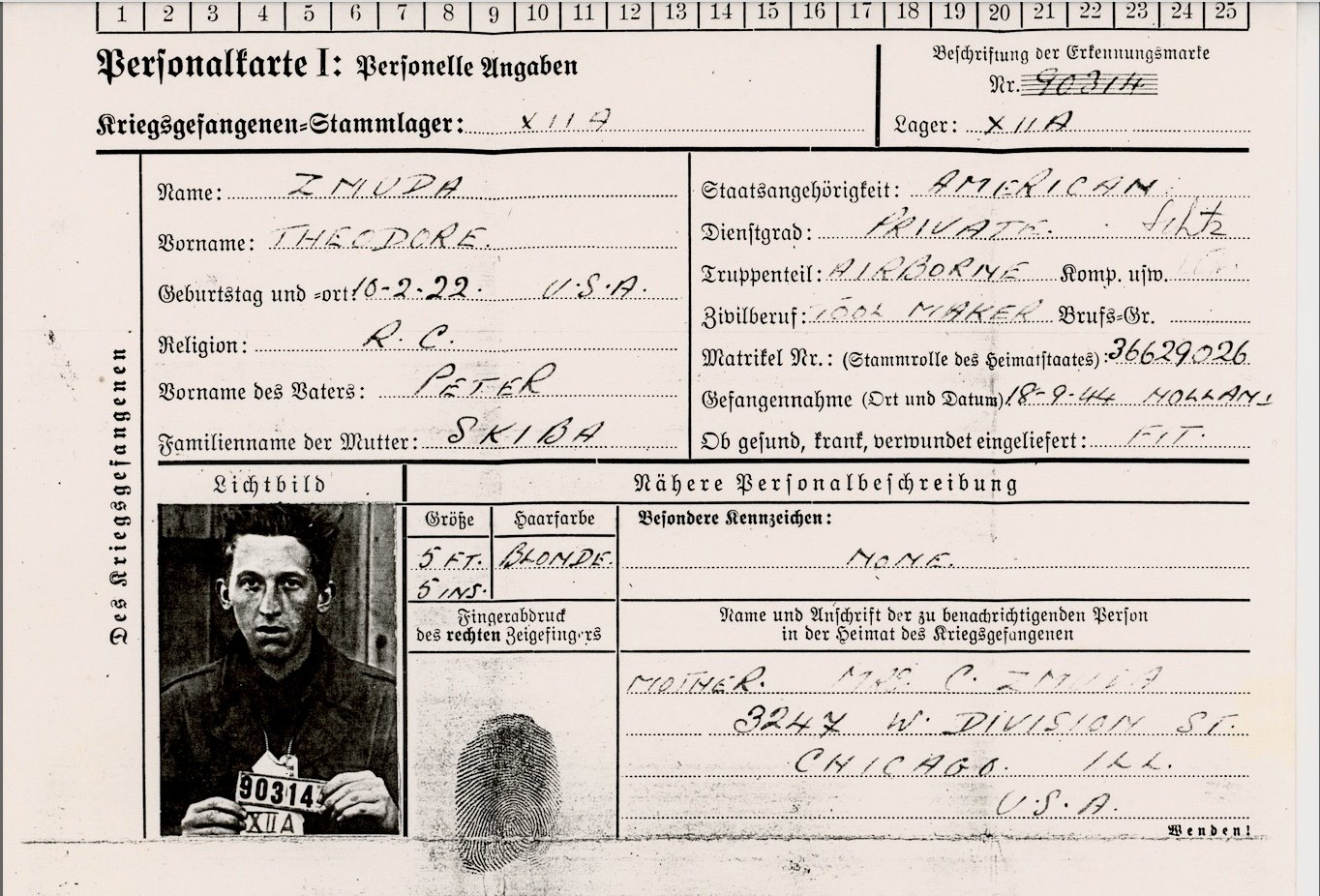

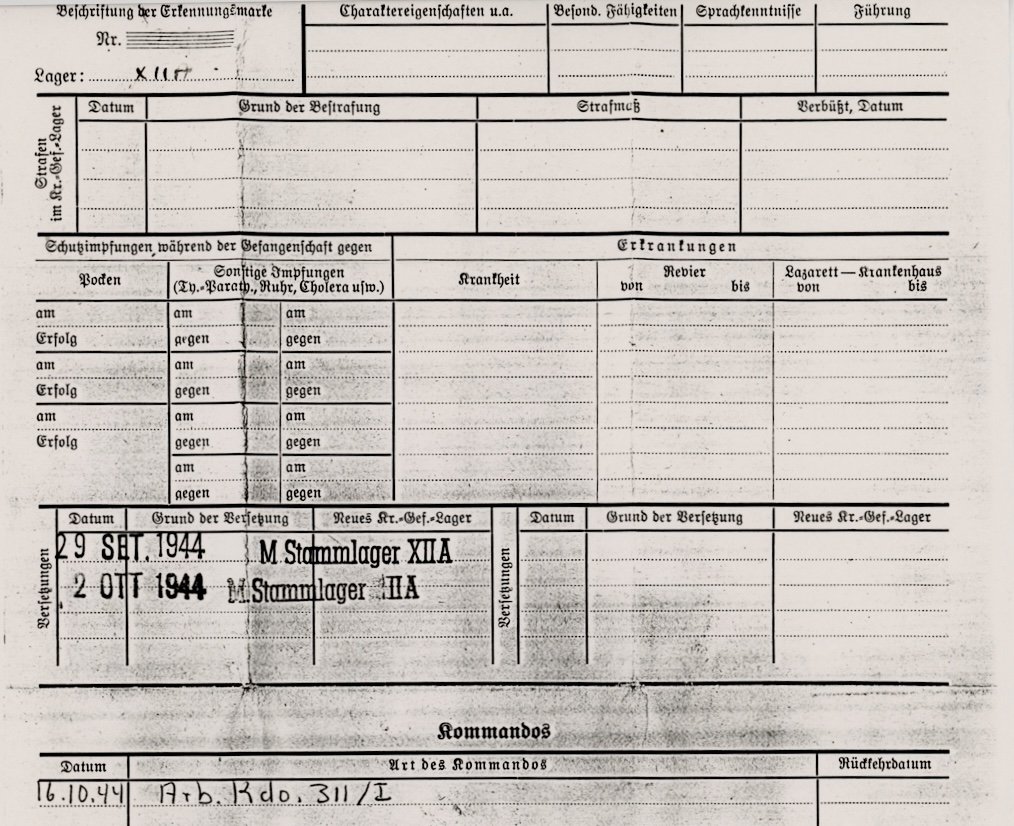

Zmuda was transported to a work camp in northern Germany, near the town of Neubrandenburg, called Stalag 311/I. Ultimately, his experience turned out to be a lot more gruesome than Elden Smith’s.

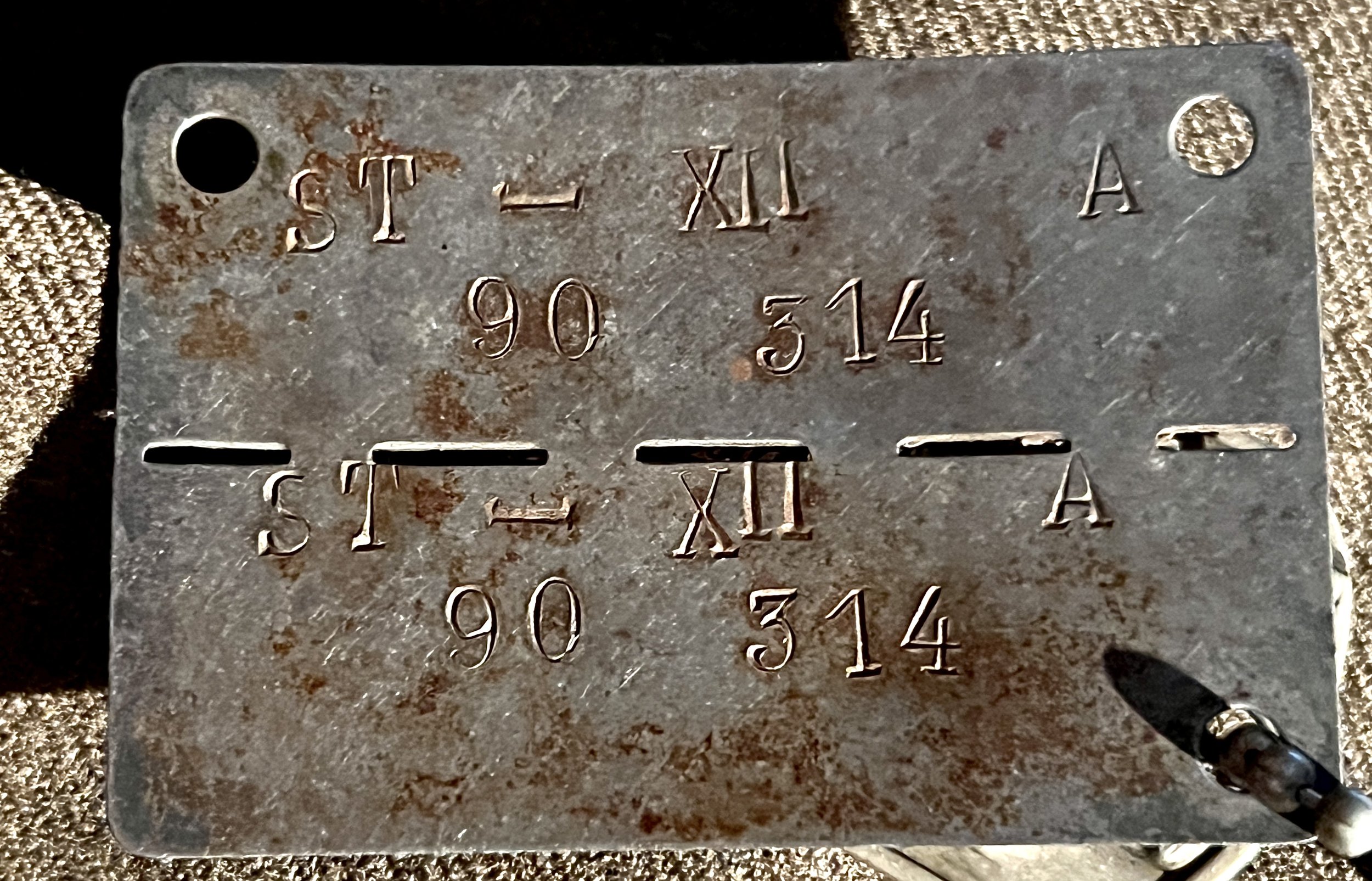

(See below Theodore Zmuda’s German POW dog tag #90314 and personnel identification presented in a slideshow fashion and side controls to the next or previous image)

Ted Zmuda was forced to spend his days doing back-breaking manual labor repairing German rail lines and rail heads after Allied bombs had destroyed them. Ted slept on the floor of a squalid, freezing, open barn in what was a former pig farm. He ate mostly bread and water. But that wasn’t nearly the worst of it.

As an aside, Elden Smith was sent to the Stalag 3C POW camp, was not grossly mistreated by brutal guards, where he was confined with 2,000 POWs for about 5 months. Elden was also liberated much sooner than Ted Zmuda because the Stalag 3C camp at which he was held was liberated by the Allies almost four months earlier than Stalag 311/I.

The guards at Stalag 311/I were former German SS soldiers, most of whom were wounded in combat or were too old to fight on the front lines. And, as with so many SS officers, their mean spiritedness and lack of human empathy made Zmuda’s guards particularly cruel and unfeeling towards the prisoners of their charge.

The true story of Zmuda’s time in the Stalag 311/I camp is documented by Ted’s first-hand account of his experiences, as told to and recounted by his daughter, Laura. She said her dad never talked about his WWII experiences while she was growing up. But during the last year of his life, he finally opened up to her about what he had lived through in the war.

The following account is Ted’s daughter’s re-telling of the stories her father told her before he passed

“When my dad’s glider crashed in Holland, they were surrounded by German soldiers. The Germans were firing a machine gun from a church steeple which kept the men pinned down. Then, German soldiers attacked from a nearby canal. Outnumbered and under heavy fire they were captured. The Germans shot any Allied soldiers that were wounded and left the bodies where they lay.”

“The Germans made their captives march for miles and miles with their arms straight up in the air, which became extremely painful. If one of the POW’s was weak or wounded and couldn’t keep up, he would be shot. The POWs weren’t allowed to touch the bodies although some of them did take the boots from the dead soldiers. Even if they were the wrong size, if your boots were worn through from walking, the wrong size was better than nothing. Ted took the boots off a dead soldier. They were too small but were superior to what he had. Dad told me that he suffered from foot trouble for the rest of his life because of that.”

“The long march and journey to his final work camp destination (Stalag 311/I) was grueling and tortuous. As I mentioned, the POWs had to keep their arms straight up while marching and if you even varied your movements a little, the Germans would just shoot you.”

“My dad was sleeping outdoors one night and realized he was lying on top of a dead German soldier. He took a small pistol off the dead man, along with 5 bullets and a holster.” (serial no. 590004 - see inset photo)

“He recounted that he really wanted to use the weapon to shoot one especially cruel guard at the Stalag. But he never did because he knew if he did that, every prisoner in the camp would suffer the consequences. Dad buried the gun and bullets in the ground at the Stalag but never shot the weapon (an Astra 9mm see photos below) during his captivity.”

“Some German soldiers were outright sadists, former SS men who lacked any empathy, sympathy, or pity. Despite their treatment Ted felt they developed over time a psychological bond with their captors. For example, the commandant of Stalag 311/I was a former kindergarten teacher whose wife was killed during the Allied bombing of Berlin. When he attended her funeral in Berlin, despite their cruel treatment the prisoners offered their condolences and genuine sympathy to him.”

“Dad told me that the prisoners were marched into a local town filled with war refugees. The SS soldiers were known for raping then shooting women, while they made the POW’s watch helplessly. The guards threatened the people that if anyone looked on, touched, or moved a dead body, they would return to the town and do it all over again.”

“The prisoners at Stalag 311/I were fed mostly bread and water. Once in a while their meal would be watered-down soup with something resembling “meat” in it. None of the men could or would eat if this coincided with anyone dying. This was not without consequence. If a POW refused to eat it might result in being stripped naked and hosed with cold water. Then they would make him stand outside all night.”

“Ted spoke of roll call in the morning. The POWS at times were subjected to snarling German Shepherd dogs that might tear him apart. Sometimes, just for sport, the guards would pretend to be nice to the prisoners and feed them hot soup. But the guards had urinated and defecated in the soup. They gloated as the prisoners ate this devil’s stew.”

Another prisoner, Dan Jones, recalled he was fed very little but worked hard. The guards would toss an apple amongst the men so they would fight over it. They were fed old bread and sawdust with grease as butter. But mostly ate turnip soup with no turnips.

Fellow soldier and prisoner Herb Marlowe recalled having a daily cup of watered down coffee before going out to work on the railroad lines. The coffee tasted like boiled rope. He was given a fifth of a loaf of bread each week. The men usually worked until 10 p.m and dinner consisted of potato soup that was mostly potato peelings. The men stole vegetables from the nearby fields when possible, mostly potatoes. Occasionally, they stole cheese which helped stop their dysentery. Their captors would give them what they believed to be tainted meat, however, their POW cook refused to cook it. Marlowe remembered having his jump boots taken away after an escape attempt and the men were forced to work wearing wooden shoes.

“For punishment the guards would also strip the POWs naked in the winter, dad and the other POWs were forced to sleep on the floor of a pig barn with no heat or ventilation.”

“The Germans would leave dead bodies on display. The indignity of not being allowed to bury their dead was just another tactic the Germans used to break the POWs of any “spirit” that they had left.”

“When the German guards didn’t receive supplies or food rations, they took it out on the prisoners. If the Germans were under-supplied, the POWs didn’t get any bread. “

“The prisoners were forced to build their own sewage pits or cat holes in the ground. Big holes in the ground which the prisoners were forced to use as a bathroom. They were just these big, awful dung holes. If a prisoner caused any trouble in the Stalag, one punishment would be to spend up to 24 hours sitting inside this hole. Afterwards, that POW wouldn’t be allowed to shower or clean off. He had to stay like that or risk another similar punishment.”

“There were no blankets, no beds, nor windows in the pig barn. They slept close together, bodies pressed into each other for warmth. And this sleeping arrangement included the men who had spent a night in the sewage pit. The smell - sickly, sweaty, horribly odorific - was beyond awful. But they endured it because there was no choice. And they needed each other in the most elemental way - so they wouldn’t freeze to death.”

“The POWs were forced to repair or replace rail lines or bridges damaged from Allied bombing raids. The physical labor of lifting and moving railroad ties and lengths of railroad track every day was bad enough. But they ate mostly bread and water, lived under God-awful conditions, had their human dignity assaulted constantly.”

“Dad was not merely skinny when he returned to the States, but skeletal and emaciated. He’d lost most of his teeth. He had no muscle tone. And he would go on to endure a lifetime of problems with his teeth, feet, and bones.”

“It was very hard for my dad to tell me his story for the first time. There was a profound sadness in him as he related what happened during the war.”

“I believe it would have been better for my dad, and the other POWs from the 82nd Airborne Division if they had told someone, some loved one, their stories sooner and gotten it off their chest long ago. My dad lived with these experiences locked inside him for nearly the rest of his life.”

On May 3, 1945, Ted Zmuda and the other POWs woke up to find that the guards at Stalag 311/I were gone. They had fled in the night because the Russians were closing in from the east and the Allies from the west. So the POWs just got up and walked away.

Ted Zmuda walks out of the POW camp, finds his way to the Allied lines, gets discharged from the US Army and repatriated back to the USA. Within days the German Army unconditionally surrendered to the Allied forces.

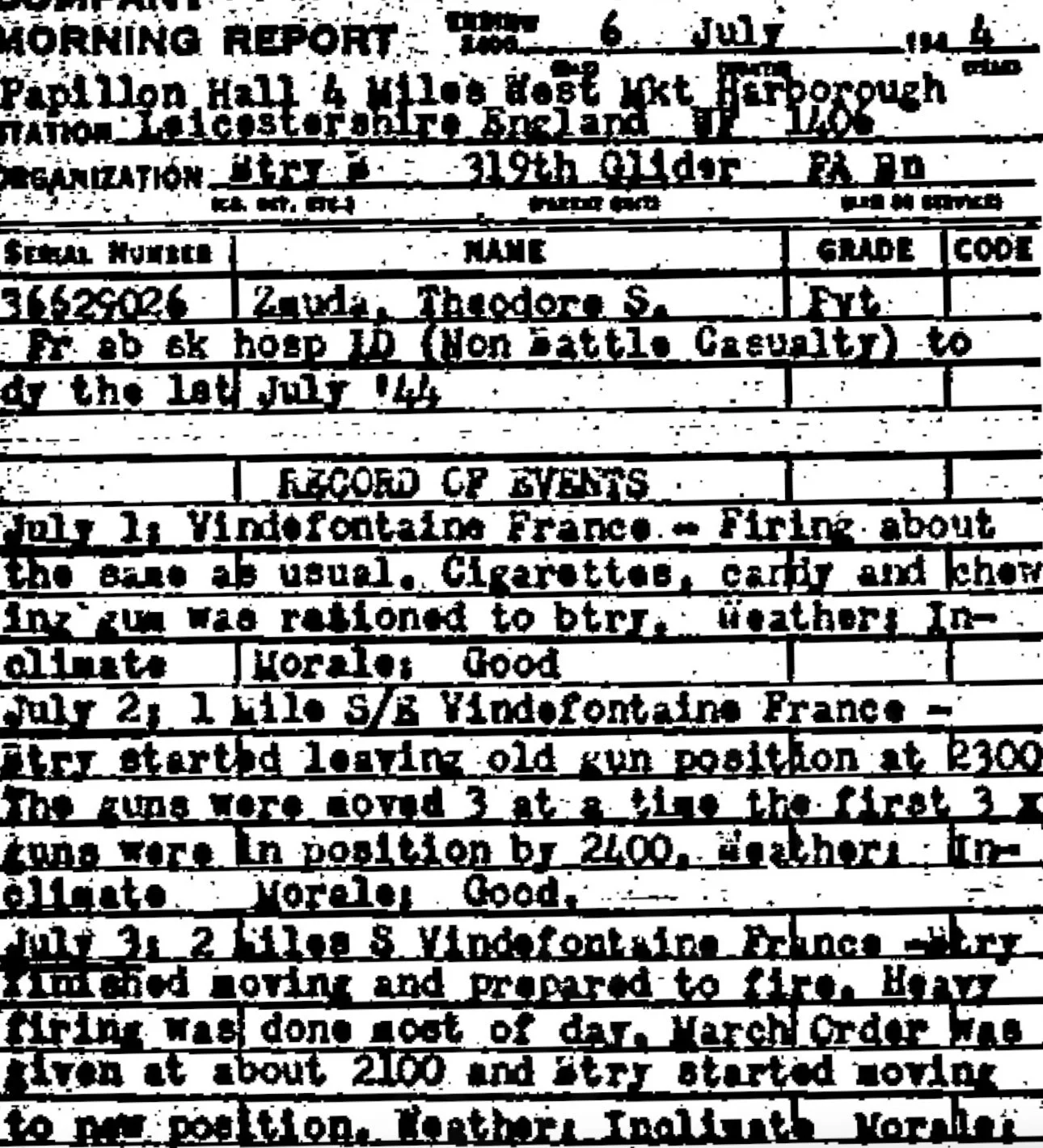

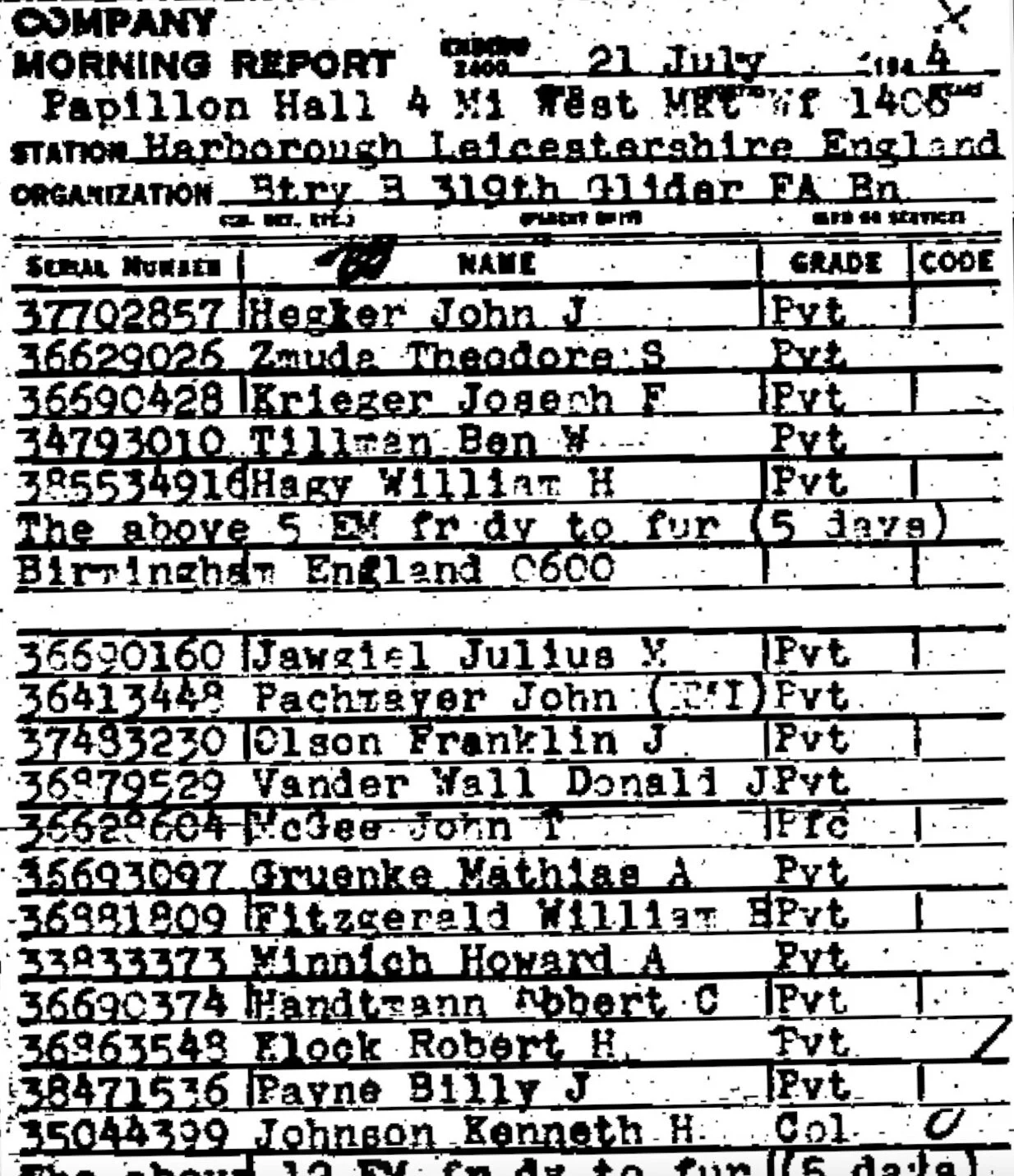

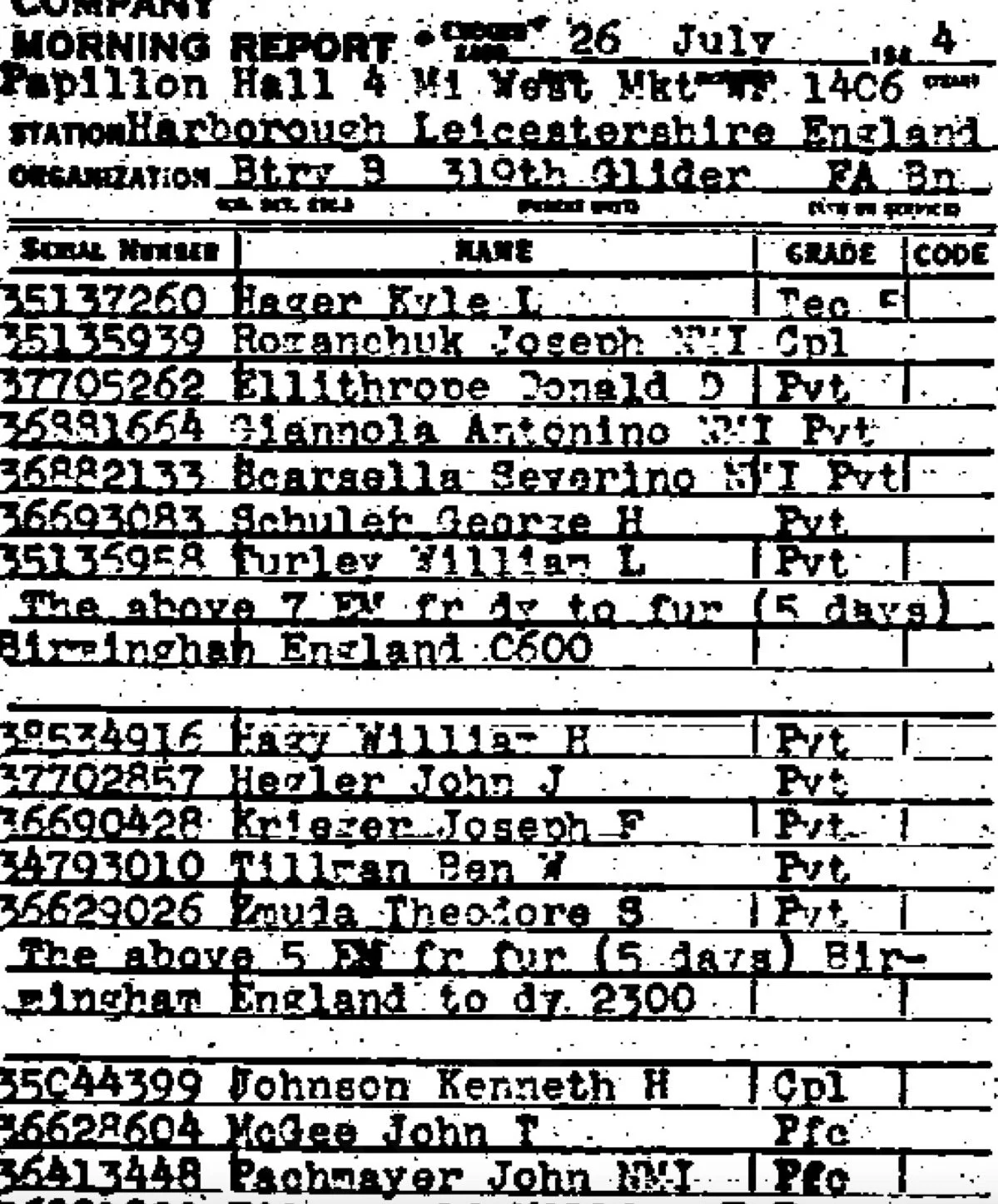

Company Morning Reports

“Company Morning Reports” were produced every morning by the individual Army units to record personnel matters.

The following events (see images below) were reported for PVT Theodore S. Zmuda.

On March 20, 1944, PVT Zmuda from duty furlough 5 days at 0800.

From furlough to duty on March 25, 1944 at 2000.

On July 6, 1944, from absent sick hospital to duty the 1st July ‘44.

On July 21, 1944, from duty to furlough 5 days Birmingham, England at 0600.

From furlough to duty at 2300 on July 26, 1944.

PVT Zmuda reported Missing in Action the 18th of September, 1944. (Operation Holland)

The US Army used the Adjusted Service Rating Score (ASR) at the end of the war to determine when soldiers were eligible for discharge.

By September 12, 1945, Private Zmuda had an ASR Score of 77. He separated from the service at Camp Maxey, Texas on October 12, 1945, and lived out his blessedly long life in his native Chicago. One of the so-called lucky ones.

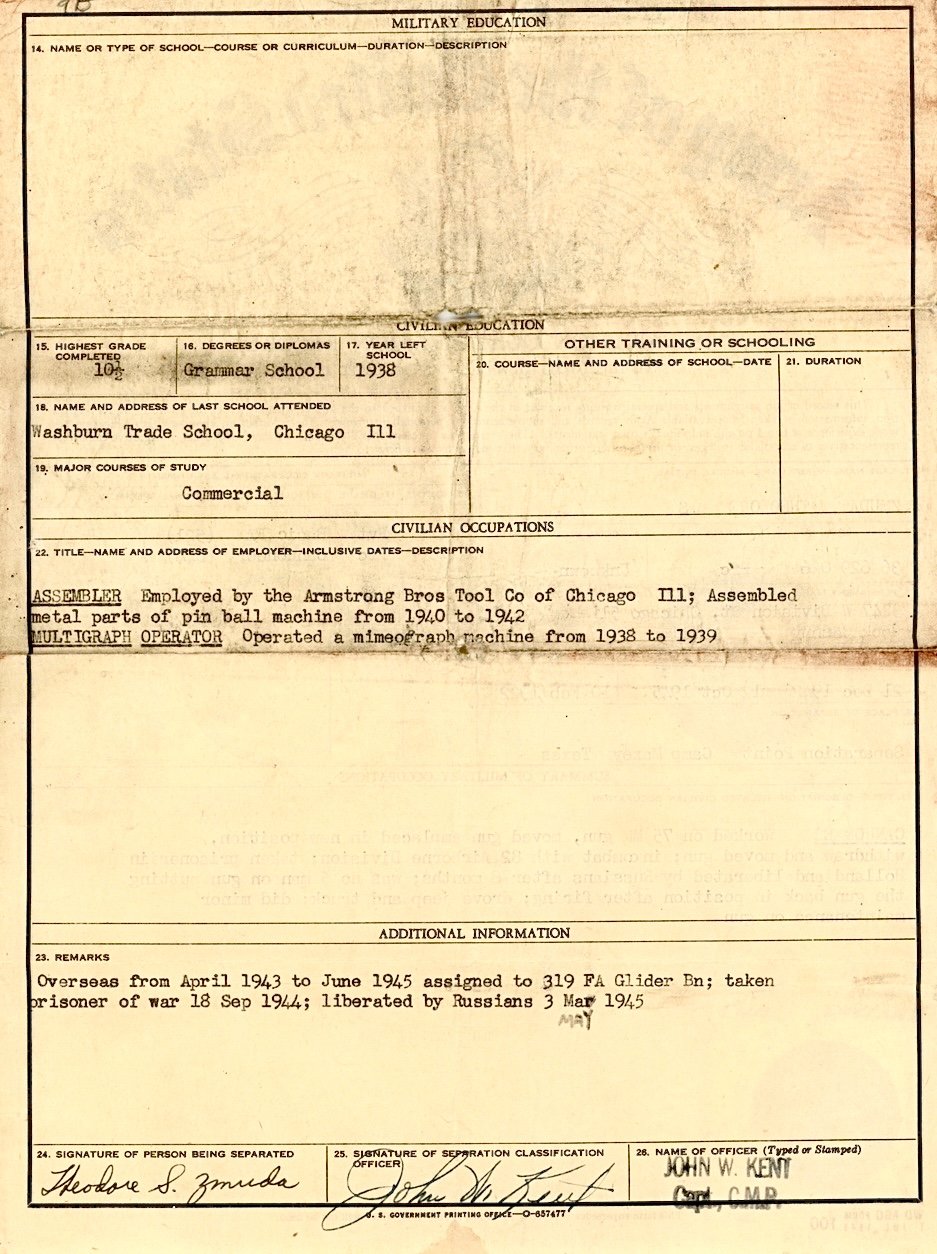

(See below Private Zmuda’s Honorable Discharge and Separation Qualification Record presented in a slideshow fashion and side controls to the next or previous image)

Theodore Zmuda was awarded 4 Bronze Battle Stars, Silver Star, Bronze Arrowhead, Good Conduct Medal, Bronze Star Medal, the Belgian Fourragere, Presidential Unit Citation Badge, Victory Ribbon, and the European-African-Middle Eastern Theatre Ribbon. (see below)

(L-R) World War II Victory Medal/Ribbon, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal/Ribbon, U.S. flag shoulder patch, Glider patch, 82nd Airborne Charter Member card, Overseas Service Bars each represents (6) months service in a theater of war, 82nd Airborne arm patch (s) and WWII Dog Tag.

Post War Years

Ted Zmuda stayed in touch with fellow B-Battery soldiers over the years. His daughter recalls visiting with the family of Steve Zwerko, a fellow resident of Chicago, Illinois, who was gravely wounded on D-Day.

He belonged to the American Ex-Prisoners of War and was a proud member of the 311/I Kommando Ex-POWs Association.

These fellow POWs and proud heroes (see photos below) gathered for annual get-togethers, men like Marvin Bell, William Kalkreuth, James Rizzuto, Herb Marlowe, Claude Arnold, Earl Mickelson, Stanley Watsick, James Bruton, Dan Jones, Paul Johnson and Charlie Chasten. A true band of brothers.

In later years they exchanged Holiday greetings, wishing each other well. And the usual comments about sore knees, declining health, and the passing of an old friend.

B-Battery soldier Myron Lepkowski of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, wrote in 1998, “I’m in the same shape as you, my knees are giving out - have to use the railing going up and down steps. Short walks is all I can handle - have to force myself. Bea and I still get around going to church and visiting the family. Steve Zwerko died from lung cancer. Joe Palazzol0 and Tom Sewell write to me - they are OK.”

In 1999, Herb Marlowe wrote, “Hope this finds you and Wanda well & happy. We don’t travel much any more, too old. Ted if you haven’t already filed a claim with the VA some POWs have got 100%. I just got 20% on frost bitten feet.”

Amongst Ted Zmuda’s personal effects was a letter written about the true meaning of a Prisoner of War and “some things you don’t forget.”

To Be a Prisoner of War

“To be a prisoner of war is to know hunger. I am not talking about the hunger you feel when you miss your lunch or when you can not stand your diet. I am talking about hunger from the lack of solid food for weeks and months. Hunger that gnaws at your vital organs and strips the flesh from your bones. Hunger that forces you to eat anything and everything available…black stale bread made from sawdust, watery soup infested with worms and made from garbage, rotten potatoes and turnips dug from the muddy fields, and, if you are lucky, hot water to wash it all down.

311/I Kommando Ex-POWs members visiting fellow Ex-POW Marvin Tanner (seated). Dan Jones, Stan Watsick, Herb Marlowe and Herbert Phillippe (L-R)

To be a prisoner of war is to experience cold. Not the cold, blustery Minnesota winter when you wish you had worn your gloves. I am talking about standing for hours in soup lines in freezing weather pelted by sleet, feet numb and fingers nearly frozen. You are sick, your body is racked by uncontrollable shivering and your mind is a mask of pain. Dysentery knots your stomach, adding to the misery. You begin to wonder if death is far away. It never comes…it merely teases you.

To be a prisoner of war is to experience fear. Nameless terror as you lie packed into a railroad box car, doors locked and barred, while attacking aircraft bomb and strafe and not knowing if you will be blown to bits the next second. The terrible fear of catching a horrible disease that runs rampant throughout the camp and no medicine or strength to fight back. The fear you might never again be free…

To be a prisoner of war is to experience anger and deep depression. Anger knowing that your enemy counterparts, imprisoned in the United States, are well fed and clothed. Thoughts of family and home lock your mind in bottomless depression and is perhaps the cruelest torture. Anger at your captors and wishing for their death.

To be a prisoner of war is to suffer the agony of rehabilitation in a suddenly alien world. It is the frustration of trying to cope and fit into a society that seems foreign and unable to relate to your experiences. It is the resentment you immediately feel for those who have never felt what you have, seen what you have, and whose personal problems pale by comparison.

It is the recurring nightmares that will plague you for the rest of your days. It is the nagging question, “What was it all for? What good did it do? Who cares?”

Perhaps there was a purpose. Perhaps the ex-POW has a clearer perspective of what is real and who is genuine. Perhaps he understands what is really important in life…”

Bill Hall, Ex-POW, ETO

Theodore Stanley Zmuda, 87, died February 28, 2009.

God Bless this hero.