William J.Reid

ASN:0-434990

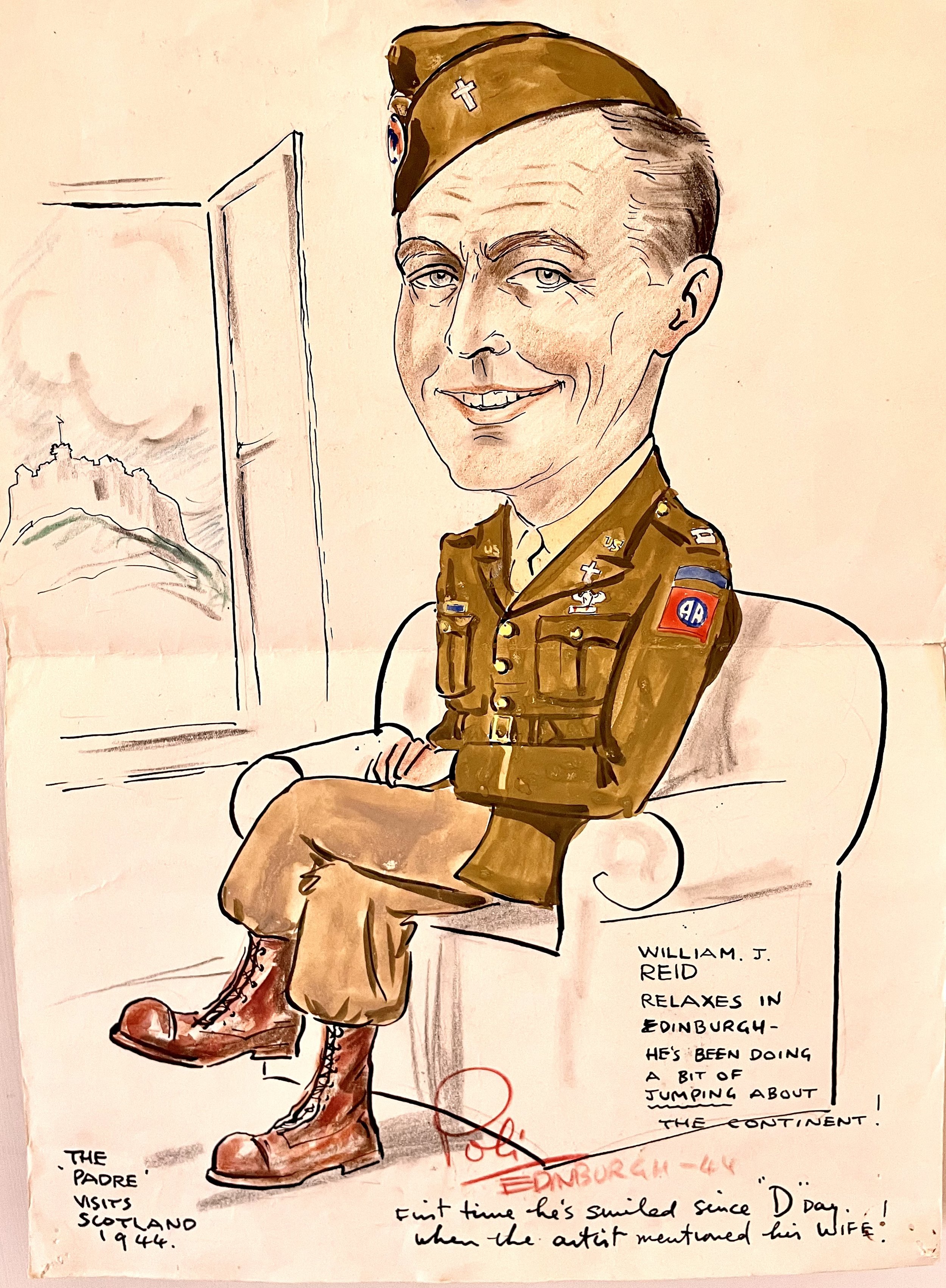

William J. Reid, Chaplain of the 82nd Airborne Division Artillery

This is the story of an American hero. A chaplain who was also a paratrooper in some of the deadliest battles of World War II.

His name was William J. Reid, and he was ultimately blessed with a long and very rewarding life (1904 - 1991).

Formerly the pastor of the Rayville, Louisiana Methodist Church, William J. Reid went to Europe during World War II with the 82nd Airborne Division Artillery and ended up a true hero. His story is documented here, and it is a complicated story. Truth be told, Reid was a complex, multi-dimensional man.

Chaplain William Reid was a Methodist minister from Texas, who later moved to Louisiana and became a key player in thein the U.S. army’s Army’s campaigns into North Africa, Sicily, Italy, France, and Holland. He was active in the Normandy invasion that changed the course of the war in Europe, and also in the invasion of Sicily and the Italian coast, as well as the Battle of the Bulge.

A BIT OF BACKGROUND: Born in 1904 in the town of Bonham, Texas,, in 1904, William Reid graduated from the University of Oklahoma in 1931 with a bachelor’s degree. He married his sweetheart, Margaret Ann Wills (whom he called known to everyone as Susie) in August of 1931. Reid then attended the school of theology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1937.

After he graduated from SMU, Reid moved to Louisiana to serve as the pastor of the Rayville, Louisiana Methodist Church, where he ministered until the beginning of World War II.

Reid attended Chaplain School at Harvard University and was commissioned as a U.S. Army chaplain in January of 1942., and He entered the service as a college graduate, a married man, and the father of two young daughterschildren. Reid went on to serve with the 82nd Airborne Division until December 25, 1945.

Reid’s journey with the 319th Glider men began in the very early stages of the war. He traveled with the 82nd Airborne to North Africa and stayed with the battalion until the end of WWII. His “high point” status of an 85 ASR score (during the war, points were given for the number of months in the Army, overseas, decorations, the Bronze Star, and the number of the soldier’s children under 18 years old) enabled Chaplain Reid to return home in the fall of 1945. It’s notable that Reid volunteered for a combat parachute jump when the allies first invaded Sicily in 1943, an event that he documented proudly in his diaries.

During World War II, his first combat jump was during the invasion of Sicily and his C-47 was shot out of the sky. Happily, he survived and was relatively unscathed. Later, Reid was among the soldiers of the 82nd Airborne paratroopers that jumped behind enemy lines four hours before the massive Normandy invasion began in northern France. It was during this campaign that Bill Reid was awarded the Bronze Star for heroic conduct in action, which we will detail later in this story.

Throughout the entire war, one of Chaplain Reid’s prime responsibility responsibilities - other than holding religious services and ministering to the soldiers - was “graves registration.” This involved the collection, identification, and burial of deceased allied soldiers. Reid’s duties also extended to enemy soldiers, reflecting the chaplain’s compassionate Christian nature.

To say that Bill Reid was intrepid would be an understatement. In his own non-combatant way, he was a true American hero and among “the bravest of the brave.” He jumped into harm’s way with little regard for his own personal safety.

Bill Reid wrote 265 diaries over the course of World War II which totaled more than 1,700 pages. Each month, he would send these diaries home. Together, these personal journals offer a unique and candid perspective on the wartime experiences of this devout, reserved, and very practical Methodist minister.

An examination of the diary excerpts throughout Chaplain Reid’s story - which appear here, but not all in consecutive order - reveals that in the midst of chaos, surrounding surrounded by a raging war, Chaplain Reid was able to live through, and record in his journal, the routine, the mundane, the gruesome and the extraordinary. And he did so bravely, calmly, and dispassionately.

On the boat ride to, and during the time he was stationed in North Africa (May of 1943), Reid wrote the following:

5 May 1943: “Came up to see if Chaplain Wood or Chaplain Rupert were conducting morning devotion. No abandon ship signal in 5 minutes and 20 seconds. This evening about 7:30pm, a guard accidentally knocked glass out of a fire alarm signal with his rifle on D deck aft. All the crew and deck officers rushed to stations. Swedish ‘safe passage’ ship, lighted up, passed on our port side.”

6 May 1943: “In office from 9am to 1pm. No AM devotion again this morning. Abandon ship in 5 minutes. Caught me unexpected in toilet at 11am. Completed reading “The Three Musketeers.”

8 May 1943: “Opened box of lemon drops and Hershey’s chocolate and left them on table. Also removed display. No abandon ship. Boat drill. Preparations for Sunday services. Depth charges heard at 8:15pm and again at 8:30pm. Deck control officers called to library for meeting with Colonel Galvin. Were told that seven subs were definitely identified and that they were on our trail. Told to have someone on duty at all times until we landed. I stayed on from 2am until 7:30am, when I went to breakfast.”

9 May 1943: “9am communion assisted by Chaplain Rupert. 100 men present and 60 communicants. Attended Chaplain Rupert’s and Chaplain Wood’s services. Came to office with Private Harold Cook of the 456th. He wanted to become a Christian. We knelt and prayed, both, after a lengthy discussion. I closed and locked the door to prevent too many interruptions. Inasmuch as his bride of six months is a Baptist in Ruston, Louisiana, I advised him to join the Baptist Church and promised to put him in touch with Chaplain Wall. Did not get to nap this day. Am on deck control until 1am. Wrote Mother’s Day letter and also wrote to Billy (Reid’s 4-year-old son) too.”

7 June 1943: “Casualties from the 505th and 456th combat team jump came in. Must have been thirty or more. Two malfunctions resulting in a death from the morning jumps, one in the 307th. General Taylor (General Maxwell D. Taylor, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division and later the 101st Airborne Division) told me this morning that I was nearer to being a paratrooper than ever before. Some pep talk. A few days ago I saw the battalion jump and one chute did not open, had to pull reserve. I later learned that the paratrooper’s back was broken anyway. The battalion jump resulted in 76 casualties, two serious. On this build up I am expecting to be a candidate for Parachute School. Hospital visits at 24:22 (10:54pm). Inasmuch as Woodward was sick, I had to get another driver and jeep for the evening. Although I was told that none were available, Captain Raibl got Thierney to take me. Went on compass march at 11pm until 4am when we returned to camp. Went to Division HQ mess where Sergeant Rodney fixed me up a supper and later coffee.”

9 June 1943: “Strong wind and a little rain last night. Went to 319th (Glider Field Artillery group) this morning to notify Private Kenneth Smith of the death of his father. Had dinner with Private Tizleman of B-Battery, who was my driver. Procured pass for Tizleman and me to visit the Medina (the oldest part of the city). A French officer took us to the 5th Army HQ to get an interpreter. We saw interesting sights, but I was mostly struck by the poverty, filth, and squalor of the place. Had lunch at the French officer’s mess in town. Very poor. Met Captain Mickley and he promised to see if he could purchase some metal cups for me. We may go tomorrow. Visited Red Cross. Then back to 52 where I visited Woodward and Captain Hufford. I wonder if I have gone too far this time. Well, I hope not and hope I come through this all so as to be back with Susie and Anne and Billy (Reid’s children, ages 11 and 4) and my mother for many happy years of peace and happiness together.”

While it’s not possible to include all of Reverend Reid’s diary entries here, the following are a few of the myriad excerpts from the chaplain’s many journals. These next few excerpts detail the Sicily invasion in which he jumped with the paratroopers. Subsequent diary excerpts are from Chaplain Reid’s time in Sicily, Italy, North Africa, France, and Holland. Not all are in consecutive order.

11 July 1943 D-Day - Sicily: “Slept well last night. Had to get Woodward to go retrieve my Val pack so that I would have uniform to wear. Had only jump suit which I was wearing. A.M. Worship: 17 present. No officer attended. Wrote letter to Susie. Came to Mediterranean Sea just before sunset. Arrived Sicily at 10:30am. Came up coast to Gela (Sicily) where we were fired on. Headed back toward the sea and put into coast between Gela and Scoglitti. All (of our jumpers) landed safely south of Vittoria. Came down on top of English radio communication unit which had been warned not to fire if German parachutists came in, but to take cover. We slept in olive orchard near vineyard and oat stubble where we had dropped. Learned from English, when we had identified ourselves, that we had missed our DZ (drop zone) and where we were. I slept soundly in one of the equipment bundles. Guard was posted for night, no trouble. Could see anti-aircraft fire and flare of incoming planes.”

12 July 1943: “Ate K ration and shortly afterward three German planes flew over very low, but we were too near orchard for them to see us. Marched to road and toward Vittoria. Picked up in jeep and ambulance. Passed two groups of parachutists. Went to hospital. Saw Captains McElvoy and Tircle. Learned of battle on previous day. Fifteen of us got on jeep and rode to 505 CP (the 505th infantry regiment). Had been there only a few minutes when two German planes came just overhead strafing. Helped Connelly and Wood in collecting and burying the dead. Dug one slit trench. Came back and found truck stopped over it and the truck could not be started or moved. Moved to another tree and dug another slit trench. Slept in slit trench and when I got cold toward midnight, pulled out my gas prevention cover and crawled into it. Very poor cover as the moisture of my breath condensed inside.”

13 July 1943: “Went with Major Wicks and Captain Floyd to see half-track in which one of our sergeants had been killed by an 88mm shell, and to see a Mark 6 tank which our artillery had knocked out. We all judged that the tank had been hit vitally by a bazooka.

Found bodies of several Germans and Italians. Investigated big house nearby. Found several large casks of wine, perhaps 1,000 or more gallons. Tasted of it. Also picked up several utensils for cooking. In the PM went back with detail to bury enemy dead. Buried 7 enemy dead and 1 Italian civilian. Part of the 376th came in including Colonel Griffin. Very tired toward late evening. Got soldier to pour water on me at a well so that I could take a bath. Again, slept in slit trench with gas prevention cover.”

14 July 1943: “Notified to be ready to leave at 9am. Went with Llewellyn and Tircle to search for the body of Lieutenant Willis. Found several enemy dead - 13 in one house - but did not find body of Lieutenant Willis. When Garcina looked tired and became irritable, I carried his musette bag almost all the way from Niscemi Road to the CP (command post). Very tired and told to take a rest for remainder of the day. Recovered blue equipment parachute for bedding and slept under the canopy of silk. Best rest and sleep since arrival in Sicily.”

16 July 1943: “Colonel Eaton sent the Lieutenant and me out to try to find some clothes, blankets and perhaps something along Army HQ. No luck. Near Division HQ found quartermaster’s dump and procured 60 fatigue suits, a dozen or more blankets, supply of towels, underwear, canteens, post exchange supplies and 5-1 rations (canned food rations for five soldiers). Waited expectantly to go on mission. Colonel Eaton suggested that I go to quartermaster dump again for more blankets, canteen cups and another field jacket. About middle of afternoon, more of Division HQ staff arrived by C-47 transport. General Maxwell Taylor and others greeted me enthusiastically. The Colonel had already told me that our plane did not return and that we were reported missing. I was told to wait until morning to set out on my (next) mission.”

Sicily - 26 August 1943: “Woke up too early and had to lie in bed until the time to get up. Spent idle moments repeated repeating to myself lines of poems which I held in my memory. ‘Eternal Goodness,’ ‘Invictus,’ ‘Earth’s Last Picture,’ ‘Out of this Life,’ and ‘In the Bitter Waves of Woe.’ Caught up on diary again. Had visit from Lieutenant Ross. Got permission from Colonel M to visit medina in Kairouan (in Tunisia) and made a tentative date with Shockley to go with me. Completed reading (the Book of) Isaiah yesterday. Had started re-reading it before the Sicilian excursion. Almost completed Horton’s ‘Our Eternal Contemporary.’ Seemed to me to be a new, not different, restatement of fundamentalist theology. Read quite a bit of poetry from an anthology of pocket editions. I plan to complete (Romantic poet Joanna) Baillie’s ‘Imitation to Pilgrimage’ today.

While in the 376th Wednesday, I heard about a sergeant in the HQ Battery who, for some violation, was not permitted to make the Sicilian invasion with the battalion. He cried all night, and on the day of departure would not show his face. His buddies reported that when planes roared out overhead, he was most sorrowfully depressed and almost to tears. Quite different than Captain Johnston another captain of the 456th, who told me he would be left behind and said, ‘Thank goodness.’”

Sicily and Tunisia - 27 August 1943: “Went to Kairouan (Tunisia) with Lieutenant Currans, which is still off limits due to typhus. We got a guide and visited the Grand Mosque, lighted by olive oil lamps, for Friday services. 9,000 attended a reading of the Koran and prayers. Went up into a tower from which, in earlier days, Muslims were called to religious services. Also went to the mosque of the Barber and saw the tomb of an Indian who built the mosque. He was a friend of Mohammed and when the prophet died in Mecca, the Barber returned to get three hairs from the Prophet’s beard. Thus he became a holy man and was buried with the three hairs in his hand.

Went to bazaar but could find nothing to buy except rugs and they were, I think, too high (expensive). There were jewelry trinkets that were also unreasonably high. Shoe making seemed to be the principal occupation as well as ring making. Our guide told us that 9,000 Arabs live inside the wall in the medina (the oldest part of the town). Flies were numerous and the stench from filth was offensive. The streets were piled with garbage, horse dung and had the smell of human excreta in the little alleys. About one in five people had inflamed eyes or were blind. All the streets were narrow like alleys, some were paved with stone or square rocks. But the mosques were clean and orderly. When you see the unsanitary conditions of the Medina you are not surprised that typhus and typhoid are prevalent. One even wonders how the people can live in such conditions at all. Our guide said that the French live outside the wall. They have modern villas that seem to be very nice and comfortable.”

Naples, Italy - 28 September 1943: “Awoke early but stayed under blankets until rather late. Had hot coffee and meat and beans for breakfast. Germans had evacuated the Naples area overnight in the valley. British tanks were pulled in from the south. Came down off mountain in about an hour. Learned that doughboys, rangers, one battery of the 80th Airborne Anti-aircraft Battalion and 504 parachutists had gone through the gap without opposition. Also, the A battery of the 319th (319th Glidermen) had been fired upon by retreating Jerries (Germans). One man was killed at his gun position. Stopped at B-Battery to get my laundry. I left it with an Italian yesterday, but my trousers had just been dropped into a tank of water covered with oil and lots of rotten grapes. Went down to 319th command post and there was a soldier named Bullinger who was brought in by Lieutenant Hawkins to be placed under arrest for shooting at our men at the C gun position. He had been drinking too much vino according to the report of medical officers Bedingfield and Hebert. Made 15 hospital visits. Back to the 80th Airborne Anti-Aircraft headquarters. Passed an engineer. Tanks and vehicles were moving up to a forward position. Got bath at the castle. Then back to 80th AA HQ.

Played gin rummy a while with the officers.”

Normandy, France - 14 June 1944 - After D-Day: “Word came in that Lieutenant Brown, pilot of one of our cub planes, was killed yesterday near the cub landing field near Sainte Mère Église. Connelly and I went there to get the body and learn details of the accident. The plane had crashed into trees upon taking off from the field and had burst into flames. The body had been removed. Connelly and I went out to the cemetery which had been established for the 319th Glidermen, near the place where the air landing strip is being established. Held funeral service while there.”

Normandy, France - 17 June 1944: “Awakened last night by the zam-blam burst of 88’s which pounded the area. About six or eight were very close, too close for indifference. I reached over and got my helmet. I always place it close to me when I crawl into the sack in the slit trench so I can grab it easily in the dark. Crabtree was very nervous. Even said that he was. I told him the shelling would stop after a little while. The shelling lasted some thirty or forty minutes. Went back to sleep and slept soundly.”

Holland - 2 October 1944: “German artillery shells fell nearby and in plentiful numbers last night. A civilian boy was struck in the shoulder by a fragment and was brought to our aid station. I woke our sergeant to give the boy first aid. While still at breakfast, a German jet whizzed overhead and dropped several AP bombs (Armor-piercing bombs used by the German air force during WWII) in our area. One hit our machine gun position, injuring six soldiers. I went to the aid station and helped give first aid to the wounded. There was much aerial activity throughout the day...our planes as well as Jerry’s jets. Those German jets are very fast. In the evening I went out to visit our men at the gun positions. On the first night there, an enemy artillery shell landed and killed one and wounded another soldier. It blew their tent all to pieces. A large tree near the point of impact had been cut down by shell fragments.

I went to the 456th command post and saw the effect of the German mortar shells, two of which hit near FDC (Fire Direction Center). Lieutenant Sharkey and others were wounded. One of the mortar shells landed near an officer who was sleeping in a slit trench that was no more than 20 feet away. He was not even scratched but was slightly jarred. Went to Holy Land Estate. Here there are replicas of important houses in the real the Holy Land in Palestine. Also, there was a beautiful dome-shaped catholic church. The place is quite famous, and I am told that tourists make pilgrimages to this Holy Land Estate, especially during the spring and summer.”

Holland - 26 January 1945 - Battle of the Bulge: “Things in stir...expecting a move this morning. Division Artillery will move in three echelons, one at 10: 00 hours (10am in military time), another at 13:00 hours (1pm in military time), and the last at 15:00 hours (2pm military time). I was to move with the last group. Due to delay for some reason, transportation, I suspect, it was decided that Major Wilcoxson, Captain Jaspin, Lieutenant Clausen, and I should wait until morning and leave at 0730 hours (7:30am). General March stayed at the house until almost dark. The five of us played hearts until he left. We ate K rations for evening chow, after which the four of us played bridge. Jaspin and I were well beaten. Captain Jaspin and I slept in the General and Colonel’s beds upstairs. Beds were very nice, and the room had an adjoining bathroom with commode, tub, lavatory, and the inevitable douche bowl” (bidet).

Holland - 27 January 1945: “Awakened about 6:30am by Major Wilcoxson who notified us that we were leaving soon. We departed from the chateau in Quarreux (Belgium) about 8:30am. Snow was deep, knee deep along the sides of the road and we had to drive in the ruts. Along the road into the town of Born we saw several bodies of dead German soldiers. Arrived in Born about 11:00 hours (11am). Found command post not yet organized and no fire in the rooms, not even in the operations room. I walked into an adjoining occupied room, the battery orderly room. Captain Raibl was sitting by the stove, Bedingfield in a chair, and Parkinson reading at a table. I spoke to all and was standing by the fire talking in a friendly way when Captain Raibl up and tells Bedingfield that he wants the stove in a room upstairs, to be used as a lounge room. This because he wants the room we were then in for business and not a visiting place. I felt the full implication and repeated aloud Colonel Griffith’s famous words about a tactical operations room. And despite Captain Raibl’s apologetic protest, I dwalked out and felt the disgust of a healthy browned off experience. In that frame and feeling, he was one whose egotism is exceeded only by his vulgarity...stinks like manure on both counts. Decided to go up to the battalion HQ and stay there rather than here.

It was after evening chow when I met the chaplain at the battalion HQ room. He told me of the German breakthrough in the sector being held by the 106th, our “Golden Lion Division.” He told me that the division was located in an area just across a valley where one could see the dragon teeth of the Siegfried Line and that they could see German troops moving around in that area. But the division was only there to hold. Officers had their footlockers with them, but of course they lost them when the Jerries broke through. Captain Stewart heard from some other officer that when the 106th Division moved into the Siegfried Line, the Germans from across the valley gave them a big public welcome. The Germans put up loudspeakers and welcomed the Golden Lion Division, which had only been overseas for four days when Jerry made the big attack. The next day the Germans gave them a big walloping artillery pounding and then came through, all but annihilating our G.L. Division. Two regiments were wiped out and the third suffered about 50% casualties.

The division’s chaplain told me that on two occasions he had found soldiers camped in the church in town. The church is only a small, inexpensive building, as are all the buildings in the town of Born. The chaplain said that he had rebuked the soldiers, telling them that they should know they were not to sleep in the church. And both times they were men of the 82nd Airborne Division. He said the soldiers of the 82nd acknowledged that they knew better. For politeness sake, I did not tell him I thought he was screwy. I’m quite sure the soldiers didn’t think it was wrong to be staying in a church. Gosh, if they’d asked me, I would have told them to go in the church and get out of the snow and cold weather. Seems like a very good use of a church at such a time. Just a difference between his Roman Catholic and my Protestant point of view.”

The Reid diaries revealed many things about the man, including his pragmatic nature, his common sense, his compassion, and his strong personal convictions, especially his aversion to foul language, debauchery, and alcohol. He was deeply concerned about the morality of the men he would minister to - both officers and enlisted men - during his time in wartime Europe. And very often, he would complain to his commanding officer, General Maxwell Taylor, about the immorality, especially when the soldiers hosted a “cat house” on the army base at Camp Suippes in Suippes, France.

For his part, General Taylor had to balance Reid’s criticisms (which the General may well have shared) with his concern for the morale of his combat soldiers. It was a real balancing act for General Taylor because while he respected (and probably agreed with) Chaplain Reid’s opinion, he also knew that combat troops could be “rough around the edges,” and needed R&R such as drinking and cavorting to keep up their fighting spirit.

Bill Reid also had peculiarities as all men do. When he wrote about anything he thought was “off-color,” he would write those words in Greek. He clearly didn’t want to write any objectionable language in English, as he found curse words personally offensive. The chaplain also enjoyed using the word “chisel.” He was often trying to “chisel a plane ride” or “chisel a hot meal” or “chisel the loan of a jeep” so he could perhaps visit historical sites in Europe or deliver something on behalf of General Taylor.

What makes Reid’s story even more interesting is the concern for his family’s financial well-being. Even while in forward combat zones he was constantly worried about his wife Susie’s ability to manage their household finances while he was away at war. At the rank of Captain, his concern for his family’s financial stability led Reid to explore additional avenues to augment his income.

Fortunately, Reid’s commanding officer (General Maxwell D. Taylor) admired the chaplain and was predisposed to helping him. Reid was able to convince the general, over General Taylor’s better judgment, to allow him to become a paratrooper. This decision - which earned him the nickname “the Jumping chaplainChaplain,” enabled Reid to engage in combat jumps even though he was unarmed. The result was that he was able to augment his base army pay with “combat pay.”

In December of 1967, a retired General Taylor wrote to Reverend Bill Reid thanking him for his service. Here’s what the General said: “I have often thought of you over the years since our wartime association and have wondered what has happened to you. I shall always be grateful for the inspirational leadership you gave our troops in the artillery of the 82nd. I hope you don’t mind my frequent retelling of the story of your insistence on becoming a parachutist over my better judgment. I had your loss on my conscience during those early days when you were missing following your drop into Sicily. I hope the postwar years have been good to you in proportion to your just desserts.”

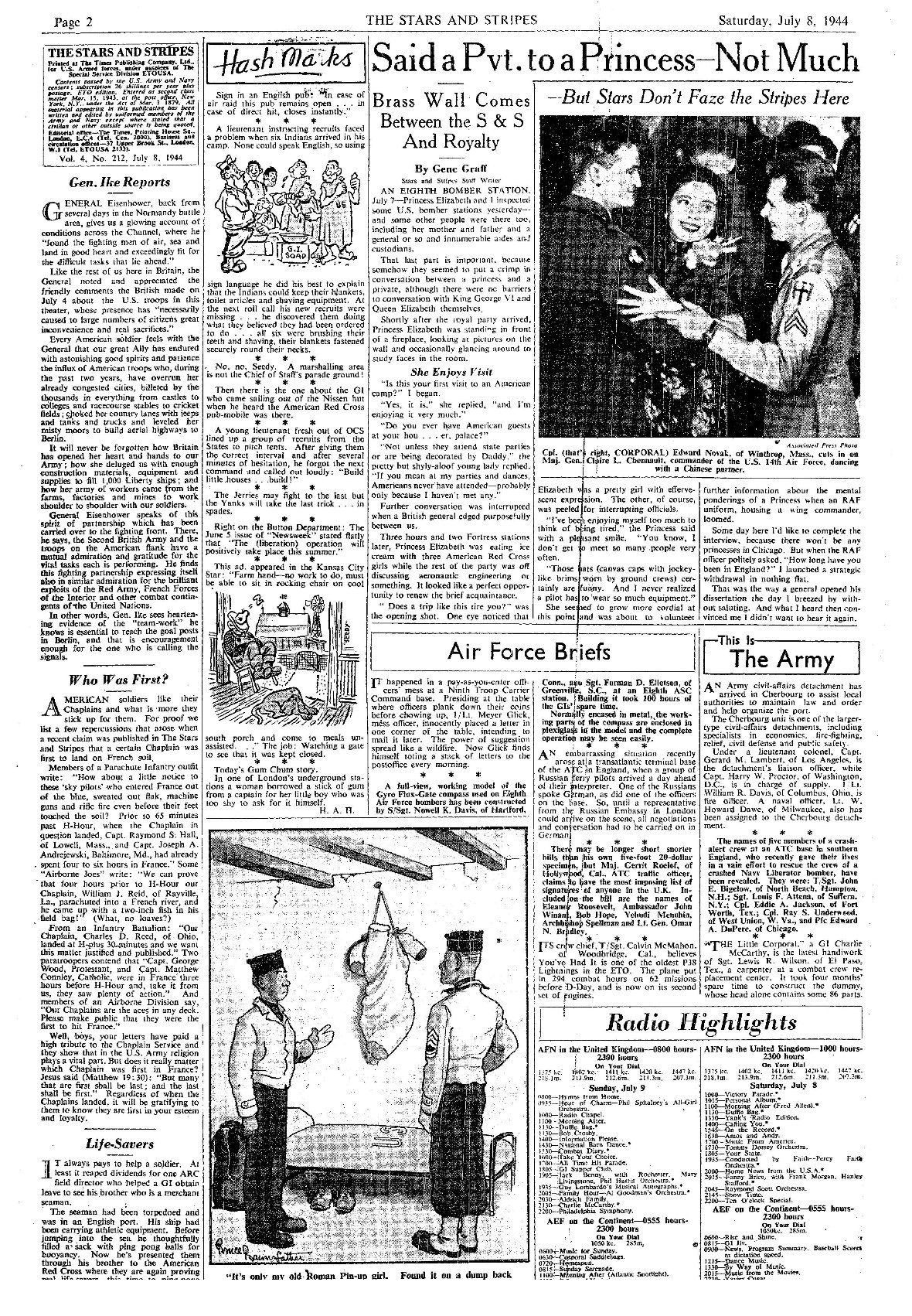

It was during his jump into Normandy, France that Chaplain Reid achieved a degree of personal notoriety. The day after the parachute jump, a reporter for Stars & Stripes, the army newsletter, was captivated by the fact that an unarmed chaplain had participated in a real combat jump. As Reid was tending to his gear, water drained from his canvas Musette bag, and two small fish fell out. This was caused by his waterlogged landing on the previous day when he descended into the Merderet river just north of Sainte-Mère-Église, France. The reporter’s remarks made a playful reference to the biblical story of the “loaves and fishes,” which caught the attention of the men who produced Stars & Stripes. And the ensuing newsletter article contributed to Chaplain Reid’s growing fame as a special non-combatant member of the 82nd Airborne Division.

According to Reid’s own diary entry on June 5, 1944, here is his unique perspective on the parachute jump into Normandy, France on that fateful day. As a chaplain, Bill Reid was one of very, very few unarmed paratroopers.

D-DAY MINUS 1: 5 June 1944: “Still raining and cold. Did not sleep well at all last night. Too cold. Lieutenant Colonel Harrison informed me that Colonel Linquist wants worship service again this PM. We are scheduled to go tonight. Put second smearing of protective ointment on my jump boots. Men in hangars are already shooting craps and playing poker with their invasion money. Conducted service as ordered by Colonel Linquist at 4pm in Regimental HQ hangar. About 300 present. Lieutenant Witcher took pictures of the service.”

“At 8:30am I fell into column and marched out to the airplane, a C47. (a Douglas C-47 Skytrain). Helped others of the stick (a load of paratroopers) get into their chutes and strap on equipment. Put my chute on at about 10:10 p.m. Got into plane about 10:30. Usual warm up and test of motors. Taxied down field about 11:30 and took off at 11:43 for France. I was number 1 in the stick. Lieutenant Shockley was our jump master. Door of the plane was open during the entire trip. Came to the English Channel about 12 midnight. 18 of us in the stick. Much smoking of cigarettes, but little talking. I was lucky enough to be drowsy during the water crossing. Every time I woke up to look below, I could see numerous sea craft. We were flying very high.”

D-DAY: Tuesday 6 June 1944: “Did not encounter anti-aircraft fire during the Channel crossing or over coast. This was one real danger which I expected with dread. Am glad it was a worry all in vain. I would much rather worry for a few hours about encountering flak and ack ack than to actually encounter it for a few minutes.

We reached the coast of France about 2:00 a.m. Lieutenant Shockley noticed land below and announced this to the men. He told the men to check and see that their harnesses were all buckled. Very shortly after, the red signal light came on in the plane. “Stand up and hook up” he commanded. One is likely to hear this with a sort of subconscious reluctance and passivity, as though the command was for others, but only for a moment. You get the full feel of its immediacy and familiarity - ‘That man is talking to me.’ I got up and missed the cable with my anchor fastener. Had to unlock it and hook it on the cable and lock it again. Made sure it was hooked and locked. ‘Check your equipment,” came the order. I did. ‘Sound off for equipment check...number 1, okay? Everybody okay?’

I moved to take up my position in the door for the jump. Planes were coming down swiftly from higher altitudes, many of them, and leveling off for the run over the D.Z. (Drop Zone). In the clear moonlight they could be seen distinctly. I was already at the door and in position when the command ‘Stand in the door’ was given. Time seemed long but I’m sure it was not more than a minute until I saw the green light on my right. Called Shockley’s attention to it and in quick response, he said: ‘Go Chappie.’

Out the door I went. After prop blast and opening shock, I looked below. Earth was dimly shrouded in a soft, thin mist and made transparent by the light of the moon. Looked like a meadow down below. Then, off to my right rear, I saw the red dotted lines of machine gun fire coming up at the bodies suspended beneath the rocking canopies (parachutes). The wind was blowing with such driving velocity that I could not check oscillation (back and forth movement). Remembered Captain Johnson’s warning about wires. Put my feet together. Could see grass on a smooth, gentle slope below. Coming in fast and knew I was going to hit hard. Feet down and gripping risers above my head as high as I could reach. ‘SPLASH.’ And my first thought was, now I’ve got my boots wet. Soon it began to appear that I might be drowned.

Water was a little over knee deep, but I was more aware of it being about arm length deep. My parachute did not collapse and in driving wind it pulled me through the water as if I had been a waterlogged chunk with soil attached. Just as I got up to a squatting position, the wind filled my chute and pulled me over and I ducked under. Weight of equipment now filled with water and being dragged caused me to be ducked under the marshy water several times for periods of such length that I all but lost my breath but did not strangle.

Tracer bullets from machine guns at edge of woods that ran down to the water about 200 yards to the rear caused me to try to not make even a little splashing sound, lest I should attract the attention of a Jerry at the gun. Realized the real danger of my situation again and again as I went under, and the water was getting deeper. Could not get to my feet at all. Such an ignoble way to die...drowned in a swamp somewhere in France. Grabbed suspension lines and began pulling them up under me.

After a seemingly long time, I had the parachute under me. I sat on the chute to get my breath for a few minutes. Others might already be out of their harnesses and on the way to assemble. And Jerry was all around us. Some (other parachutists) might be having an even more difficult time than me. I was so exhausted when I did get out that I was weak. And was a bit surprised to notice how difficult it was for me to stand up. It was quite a bit later that I discovered my difficulty was due to the fact that my first-aid bag and all its big pockets were filled with water, which did not drain out easily.

Had barely got away from my chute when a plane began roaring over the same drop zone, dropping more parachutists. It was quite sickening to see the red dotted lines of tracer bullets bending and swaying up towards men suspended in floating parachutes. I was making my way in the direction of the planes toward a form dimly seen which I hoped was Smitty (a fellow parachutist named Smith). Before reaching him, a paratrooper landed in a swamp just over a fence on the other side of which was a narrow drainage canal about 5 or 6 feet side that ran through a swamp. Drawing nearer to the dark form, now motionless, I heard a male voice say, ‘Flash.’ (proper challenge) With a feeling of joy, I replied, ‘Thunder.’ (password) Smith was barely out of his harness.”

“I told him about the paratrooper who had landed a short way over and suggested we go and lend a hand. On approaching, the paratrooper ceased to move. Thought he might be hurt though I had seen him moving to get out of his harness. As I got closer still, he suddenly sat up with effort, combat knife drawn. When I spoke, he uttered a sigh of relief and asked us to help him cut his harness loose. After much sawing with my knife on his webbing, we got him out and on his feet. The three of us made our way along the edge of the ditch, where I sank up to my neck while crossing. Eventually we made our way through the water to a small road and up to a railroad. A large group had assembled there. We found Shockley, Sullivan, and others of the two plane loads from Division Artillery. Soldiers were just milling around seemingly with no purpose or leader. I asked Lieutenant Shockley what we were going to do.”

(Again, it was during the June 6 D-Day invasion that the two small fish got into Chaplain Reid’s Musette bag, which prompted the story about the “Loaves and Fishes.”)

Subsequent to the airborne assault during the Normandy landings, known as H-Hour, an “Airborne Joe” wrote that he saw a near miracle, “Our chaplain, William J. Reid, parachuted into a river in northern France and he came up with a fish in his field bag! It reminded me of the miracle of the “loaves and fishes” in the Bible. What, no loaves of bread?” the soldier wrote.

After being awarded his Bronze Star (see below) for heroism, an article appeared in Reid’s hometown newspaper in Bonham, Texas that focused on their local hero, Chaplain Reid, and the fact that he had received this high honor for his heroic conduct in action.

The article stated, “The award was made for heroism in Normandy on D-Day. Chaplain Reid, a member of a detachment isolated in enemy-held territory after landing by parachute, exposed himself to enemy machine gun and small arms fire on numerous occasions in order to successfully gather together into one unit isolated parachutists who had landed nearby. On this occasion he, without regard for his personal safety, entered a field under enemy machine gun, machine pistol and rifle fire to go to the aid and comfort of two dying enemy soldiers.

‘Chaplain Reid’s courage and devotion to duty was an inspiration, and an outstanding example to all those present, and exemplified the best traditions of the military service,’ orders citing him said.”

Award of the Bronze Star Medal

To paraphrase a combat troop in his parachute infantry outfit in World War II, “Let’s give a little notice to the sky pilots who entered France from the wild blue yonder, and sweated out flak, machine guns and rifle fire even before their feet touched the ground.”

Another admiring soldier noted that “Our chaplains were the aces in any deck.” And Chaplain Bill Reid was certainly no exception. He provided aid, comfort, stability, and a sense of right-ness to all the soldiers with whom he served.

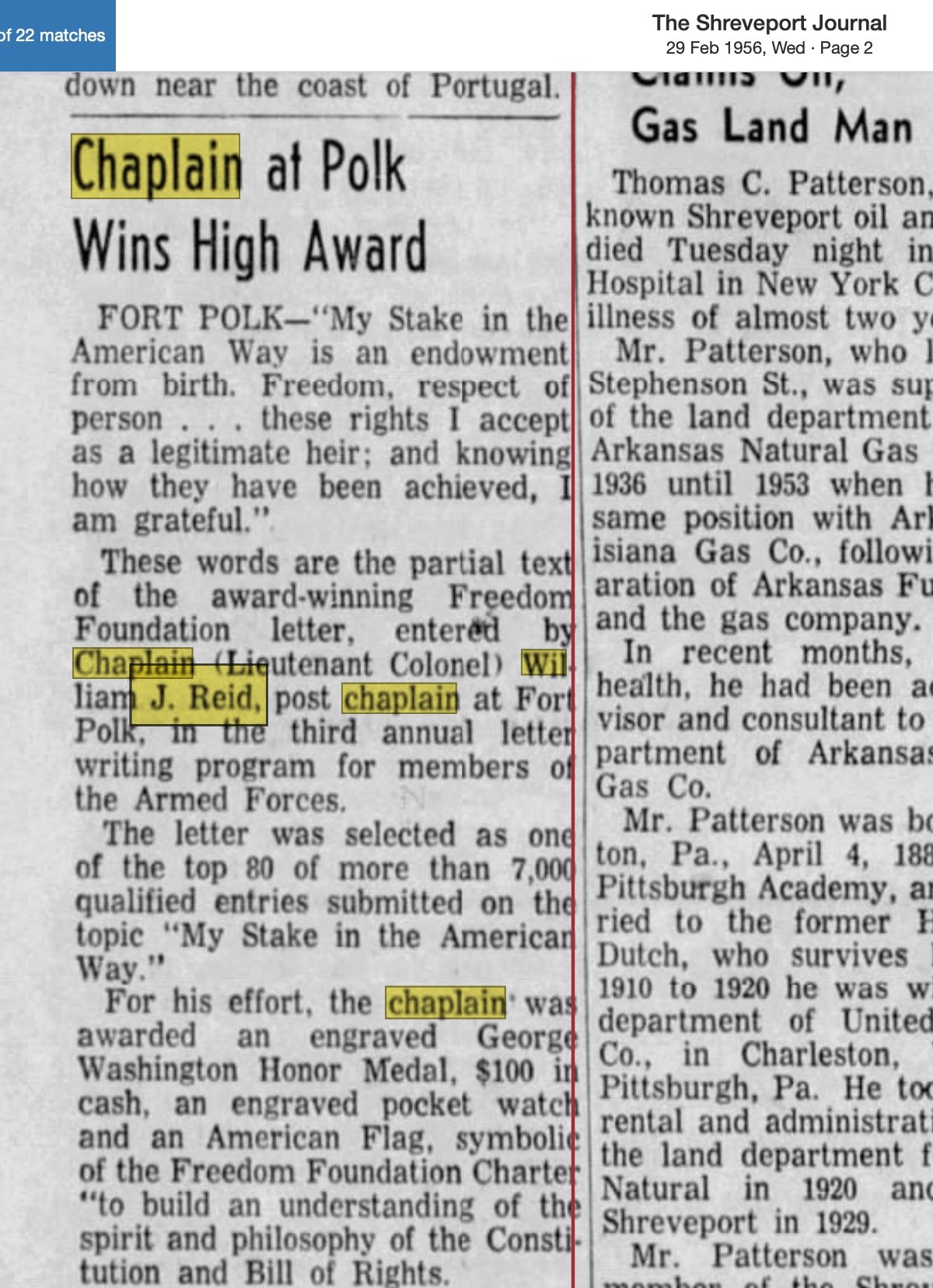

William Reid remained in the army reserve after the war and was called back to active duty in September of 1950 for the Korean conflict, serving in Japan and Okinawa.

During World War II, as was previously noted here, Chaplain Reid’s first combat jump was during the invasion of Sicily when his plane was shot out of the sky. Happily, he survived and was relatively unscathed. And ultimately, Bill Reid survived North Africa, Sicily, Italy, Normandy, and Holland. Truly, one of the luckier soldiers, and one of the blessed.

In 1959, after Korea, Okinawa and a brief assignment in France, Bill Reid (retired with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel) and his wife, Susie, returned to Louisiana.

Bill Reid resumed his career as a civilian minister in the Methodist Church where he became a staunch defender of the civil rights of all people, black and white. He remained in the reserves and retired with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in 1959.

To quote the chaplain who performed Reid’s funeral, “Bill Reid was a fighter and a soldier of the Lord. He received and endured considerable opposition during the early days of the civil rights movement including threats of physical harm, which were in retaliation for his defense of human rights and his persistent preaching of the Gospel of Jesus Christ concerning human rights, human dignity, and a Gospel of Love.”

Reid’s brave support of civil rights in the Louisiana of the 1960’s made him unpopular to many during that time of great tension in the American South.

“But Yet, even in the darkest moments,” his youngest younger daughter reminisced, “[Bill Reid] could make [his family] laugh and forget for a while the fact that hate, prejudice, and injustice seemed d to be overwhelming.”

The Reids retired to Mountain Home, Arkansas, in 1973, where Bill served as Minister of Visitation at the First United Methodist Church.

In July of 1989, the Reids moved again, this time to the Air Force Village II in San Antonio, Texas, which is where Bill Reid died in 1991, at the ripe old age of 87.

At the funeral, his younger daughter Marisu wrote, “To use a line from one of my favorite movies, It’s a Wonderful Life, here’s to Bill Reid, the richest man in town.“ And so he was.

“Copyright © 2021 Mary ‘Marisu’ Reid Fenton, All Rights Reserved; Reprinted With Permission. No part of these materials may be reproduced, stored, transmitted, or disseminated in any form or by any means without prior written permission from Mary ‘Marisu’ Reid Fenton.”

Coming soon.

Below is a memory of Chaplain Reid following his passing. It has some content.

Ft. Bragg, Winter 42 -43