John Girardin

ASN:36629013

SGT John Girardin

John Mario Girardin was born September 16, 1922, in Pioveni, Italy, a province of Vicenza. He and his mother immigrated to the United States in 1927. The Girardin’s settled in the area of Rockford, Illinois.

He registered for the draft on June 29, 1942. Girardin’s registration card indicates he worked for W.F. Barnes Company at the time. This nineteen-year-old was 5-9, 175 pounds with a dark complexion, hazel-colored eyes and brown hair.

Drafted into the Army on December 1942, PVT Girardin was inducted at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. He shipped out by train to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, December 28, 1942, where he received his initial training and assigned to C-Battery, 319th Field Artillery Group, 82nd Airborne Division. After the Italy campaign Girardin was then assigned to A-Battery.

In a 2005 interview Girardin recalled, “our first instructors (Fort Bragg) were all from the paratroop units. We had a couple of old timers, regular army drill instructors. The first group, the paratroopers, after a while they left. But the old army guys, a couple of them stayed with us. Then, artillery training on mockups of gliders. When it was time to train on gliders in flight we went to Pope Field.” He described learning assorted knots for tying down the equipment in the glider (see photo below) and dealing with motion sickness in glider flight.

Howitzer tied down with nothing more than knotted rope in a CG-4A Waco glider

Most memorable was the “the sound of the wind and turbulence caused by the propellers from the tow transport) but the gliders weren’t bad flying. It wasn’t too bad landing either because you’re landing right on the airstrip in training.”

The gliders had “benches on the side, I wouldn’t call them seats and no seat belts. Then, a jeep was in the middle and tied down in the American glider. But there was room for only one thing, a gun (Howitzer) or a jeep. (see photo inset) Or just one trailer to haul equipment.”

The 319th was regimented, “C-Battery stayed with C-Battery, same with the other batteries. The Headquarters Battery, those men were also in the Signal Corps. At Fort Bragg we lived in two-story wooden barracks. Each battery with their own mess kitchen and cooks. The guns we trained on were 75mm pack howitzers. And actually, another kind of 75 mm howitzer from the first world war, instead of wooden wheels they had rubber tires. Basically, a WWI gun with rubber tires,” he recalled.

“I never had a furlough,” Girardin remarked, “I left home December of ‘42 and I didn’t get back to Rockford (Illinois) until November of ‘45. I never had a day off, well, they gave you a day pass so you could go to Fayetteville while we were in North Carolina but you and a hundred thousand other people too.”

PVT Girardin shipped out to North Africa in May 1943, aboard the SS Santa Rosa:

Girardin remembered, “The way I recollect it, it was a cruise ship that ran from Florida to South America. We had our meals on the ship, they gave us a meal ticket and punched the ticket when you went through so you couldn’t go back for seconds. Where the mess hall was the cooks had these large kettles, then we had tables that were chest high. No place to sit down. Just put your mess kit on the table and eat. When you went down you stood in line every time. When you were done the whole line would move and somebody else moves in. They were just like that, there was no sitting. No seats, all standing. I had twenty-two meals on the ticket. I think I only ate nine of them. They started breakfast at four thirty in the morning and they quit at eleven. Then they would start serving supper at four o’clock in the afternoon and keep going till eight o’clock. I was so sick, some of us would go up at night then go down to sleep during the day and up again at night. I got sick there. Most of the time I just stayed on deck”

But on deck, “ Submarine alerts, oh yes, we had a few. We had a couple at night, you could hear the warning signals go off. We hung around, that’s all. They wouldn’t say anything. All they’d do is look around to see if they had any problems.”

As far as gear, “the enlisted men’s personal gear was in your barracks bag. Just had your basic uniform with you. Basic uniform and a couple of changes of underwear. Our uniforms were khaki at that time. I don’t think we got our duffle bags until we got off the ship. If we had our duffle bags in the state room I don’t see how we could have moved around. It was crowded. We left about the 29th of April, and we arrived at Casablanca on the eleventh of May. Just a few days after the Germans surrendered in Africa.”

Girardin talked of Casablanca, troop movement in North Africa, living conditions, training and nightly air raids by the Germans:

“By the time we got to Casablanca the Germans were gone for quite a while. We got off the ship and got our duffle bags. Then they put us on trucks. They brought us up to a farm. This farm was a bean field. That’s where we bivouacked. We put up our tents and were there for a week or so. They’d give us a pass for Casablanca. It was like any other old European town but with a lot of Americans around. It was the first time I ever seen a bathroom with the hole in the center and a platform on each side and a tank above for the water. That was the first time I ever seen that. I never seen anything like that in the States.”

SGT John Girardin -Epinal, France

“It was hot. You know what it was, you remember that movie Casablanca? It was funny, we seen that movie in the states before we went overseas, it was nothing like that though. It was a regular town, GIs running around, mostly GIs who had an afternoon or day pass. My friend and I went into town, and we noticed nobody was saluting officers. So, we did the same thing but this officer, one of these ninety day wonders, he stopped us and wrote us up. Oh, about a month later our captain called us in. He said he got a report on us, and we had to pull extra duty for a couple of weeks.”

Girardin recalled, “After Casablanca we went by rail. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of those forty and eight boxcars, forty men or eight horses. We were four days and four nights in one of those. All sleeping on the floor. If you had to pee you had to get up and try not to step on anybody. You go to the door and open the door and pee out. Then every time we stopped all the fellas would get out of the boxcar. They’d take out these little kerosene stoves and try to heat up water for coffee. By the time the water is ready in the canteen cup the whistle blows and everybody had to run back. We never had any hot meals at all. We ate K-rations, D-bars like you were in combat, stuff like that.”

“I wouldn’t know how to spell the name of the place, but we arrived there at night. They had a Red Cross doughnuts and coffee center. They were giving out coffee and a couple of doughnuts. Anyway, we unloaded, well, before that they sent some fellas out. Then we went by truck or jeep to the place where we were going to bivouac. So, when we got there they brought us out to a big field and we just went to sleep on the ground figuring in the morning we’d put up our pup tents. Well, in the morning I woke up I could hear singing or Arabs talking. It was these Arabs cutting the wheat down around that area. After we were there for a while, all the guys came down with dysentery. Oh man, what a mess that was. They had the latrine with like canvas walls set up around it and you always stay near the canvas walls, you didn’t want to get too far from there.”

Remembering the heat, “After that bivouac area they took us to another area in an olive grove. We went by truck. The border of the olive grove was cactus, seven or eight feet high. That’s where we bivouacked. It was too hot to do anything during the day, so we went out at night and continued our training. All dry runs, setting up the guns, breaking them down I don’t remember firing any guns. The officers time you on how quickly you could unhitch the gun and set it up, one gun would be in competition with the other. We were sleeping in pup tents, the olive trees only allowed for them, no pyramid tents. After washing our fatigues, we hung them out to dry (on trees and cactus) they would become bleached almost white. They almost were white by the time we got done with them. We washed the woolen uniforms in gasoline, not water. We wore canvass leggings in Africa. After the olive grove we went outside of Bizerte (Tunisia) and stayed there for a while. We were bivouacked pretty close to the buildings and had a chance to get fresh fruit. I remember the Arabs coming out to sell us grapes and everybody was coming around for the fresh fruit. That was the only fresh fruit we had. The coffee was really bad in North Africa because it was K-ration powered coffee.”

About their weapons, “We had the M1 Carbine. First we had the solid stock, then they come around with the folding stock. But we never shot anyone, never had the opportunity. We were fortunate in that we never had to defend ourselves. No sidearms, the only sidearms I remember were for the sergeants, they had them. I think only the sergeants had them, everybody else carried the carbine all the time. The C-Battery was set up with these smaller 105s (howitzer), they were nice guns. They did have a split trail (carriage) on them. The 75s had the solid trail. They jump around like mad. The aiming circle is how you set up the guns to know the direction. Someone from headquarters battery set up the aiming circle, you only had one to line everything up. The batteries operated independently but it was all 319th, you’d have A-Battery over here and B-Battery over there. But not far apart, that’s why the aiming circle was important so up to a certain point they (rounds) were all landing pretty close together no matter if you were a hundred yards apart or less. It was technical, you’ve got to have the right charge, the elevation, how far you want to go, what target to use…and then whether to have armor piercing shells, or explosive shells. You could set the firing mechanism for air bursts, I think headquarters did all that figuring out. As far as I know, we had the ammunition, they told us what to do. They want air bursts and we’d set the shell up for air bursts, they knew how far the shell goes and how high up they want it to burst. Then they had one that is a delayed action. When that shell goes into the ground it doesn’t even explode on impact. Before it bursts it goes down so far. You could pick delayed action, explode when it hits the ground, or otherwise it’s an air burst. It was on the cone of the shell.”

“When we were in Bizerte we had an air raid. The Germans dropped some bombs on us but as far as I know it didn’t cause any damage to our outfit.”

Maiori, Italy - first combat:

Girardin recalled the 319th landing by ship on a beach at night. “It was one of these good-sized landing craft. The doors would not drop open, they would swing out from the bow of the ship. While on the landing craft for the invasion we went right by a big cruiser. I don’t know if it was the Philadelphia or what, but anyway, they had an air alert and were hit by a radio guided bomb. I remember that.”

(R-L) Charles Grigus, Bob Dickson, John Girardin, William Kennedy, unk, taken June 1945 - Epinal, France - courtesy of Charlotte Sartain Provenza

“We stepped right off the ship right on to the beach. I still remember that night because there was a wall (where beach met the road) and everyone was worried the Germans would have machine guns on that wall waiting for us to land, but all we heard were a couple of dogs barking. We landed without any trouble at all. We didn’t stay on the beach. We had to go up a hill and we had a fella in front of us, because we weren’t allowed to use any headlights, this fella with the flashlight would walk ahead of us and make sure we didn’t go too far over and tumble down the mountain side. It wasn’t a very big mountain, but it was hilly. When we stopped we were put into a vineyard. That part of the mountain, it’s all vineyards and that’s where we put our gun battery. We were part of C-Battery at this time. This is the first time the battalion was firing live ammunition at the enemy. We were trying to cut that road that the Germans were supplying their beachhead with.”

“We supported Darby Rangers at the time,” Girardin said, “I didn’t see anybody get killed. We were fortunate. The Germans never sent any counter-battery at us. But A-Battery got hit by mortars. I know that because we had a company clerk who got sick after we landed in Italy, and they kept him in the hospital. He heard a rumor we would start moving out and he didn’t want to be left behind. So I remember him walking right by our battery and back to A-Battery. While he was there, they got a mortar attack from the Germans and he was one of the fellas that got killed. That’s why it sticks in my mind. He was from West Virginia, Charlie Spainhour was his name.”

“You always have that feeling the Germans were gonna throw something else at you,” Girardin remarked. “The biggest scare we had in C-Battery was one day a fighter plane went over us, all of a sudden you hear a large noise coming down that scared everybody. Come to find out it was one of those empty fuel tanks dropped from our fighters. They make quite a noise when they come down. It sounds like a large projectile coming down at you, can almost see it coming down in the daytime. But we were dug in good, a foxhole just behind the gun. The guns when set up were where at least ten to fifteen yards apart and you always kept your M-1 carbine with you. You never know when you’ll need it. There were five or six guys on a gun crew.”

When asked about the artillery, Girardin commented, “Is it pretty much the same deal, firing the 105 or the 75, one is just larger in diameter. A small trench was dug for the trail of the gun to lay in so it would not jump right or left when fired. The powder bags in with the shell determine how far you want the projectile to go. You pull the nose off and there are bags of powder inside. You use as many as is proper for the distance you want. You set the fuse on the nose for air burst, delayed or whatever. We also had armor piercing shells. They were mostly against tanks. After you fired it took only a couple of minutes to get the gun back in position.”

On October 1, 1943, the 319th moved off their position on the Chiunzi Pass. Girardin said, “I remember going to Naples that day because our first bivouac was there, we got there at night. And had to dig our foxholes, I remember somebody telling us to make sure we didn’t have any Germans around there, crawling around, because they’d cut your throat.”

Entering Naples Girardin commented, “they had an army wagon where you could buy coffee and bologna sandwiches. Anyway, we were around town there and we got talking to this guy. We were with Sergeant Goff. We started talking with somebody and he was a reporter for the Stars and Stripes. They had a mess hall for the 1st and 2nd army headquarters, what was called all the headquarters companies and they wouldn’t let you in to the mess hall. They wouldn’t let you in at all. So, after going through and getting our sandwiches we were gonna go home, you know. The reporter said, come with me. We can’t go in! He says, I’ll get you in. The guard says at the door we were not allowed. Well, I am, he said, I’m a reporter from Stars and Stripes and this fella is my brother and these two are his friends. We’ve come together to eat. The guard let us through, and we got in there. We had pork chops. After that we decided to go to a nightclub. We had to pick up this truck but it wasn’t ready or something like that. So we went to this nightclub, they had a band there and there were a lot of people. So, we drank. We drank nine bottles of champagne. Ten dollars apiece at that time. We were so loaded that every time the band played a song, we gave them ten dollars!”

Northern Ireland:

Completing their occupational duties in Naples, the 319th sailed to Northern Ireland for training and replacement soldiers. Girardin recalled, “they used to make us go out with a wheel barrow and shovel, we had to shovel water from puddles into the wheelbarrow. On guard duty, each man would try to be dressed as neat as possible hoping to be picked for best job. Such as keeping the stove going in the mess hall all night, I remember going through the mess hall keeping that fire going. I also remember once we heard this funny whistling noise which scared the men, thinking it was a large bomb. But it was only our P-38 Lightning fighter aircraft flying overhead.

Photo below, the 319th A-Battery barracks Camp Ballyscullion, Northern Ireland. (photos courtesy of John Girardin and Joseph Covais, author of BATTERY)

(L-R) Billy Cadle, Bart Plassa, Bob Rappi, “okie” Olkonen, Art Forsman, Paul Massie, John Girardin (kneeling)

Girardin went on to fight in 5 more battles and campaigns; Normandy, Northern France, Ardennes, Rhineland, and Central Europe. He was awarded 6 Bronze Battle Stars, Bronze Arrowhead, Good Conduct Medal, the Belgian Fourragere, Military Order of William, Glider Badge, Presidential Unit Citation Badge, Victory Ribbon, and the European-African-Middle Eastern Theatre Ribbon.

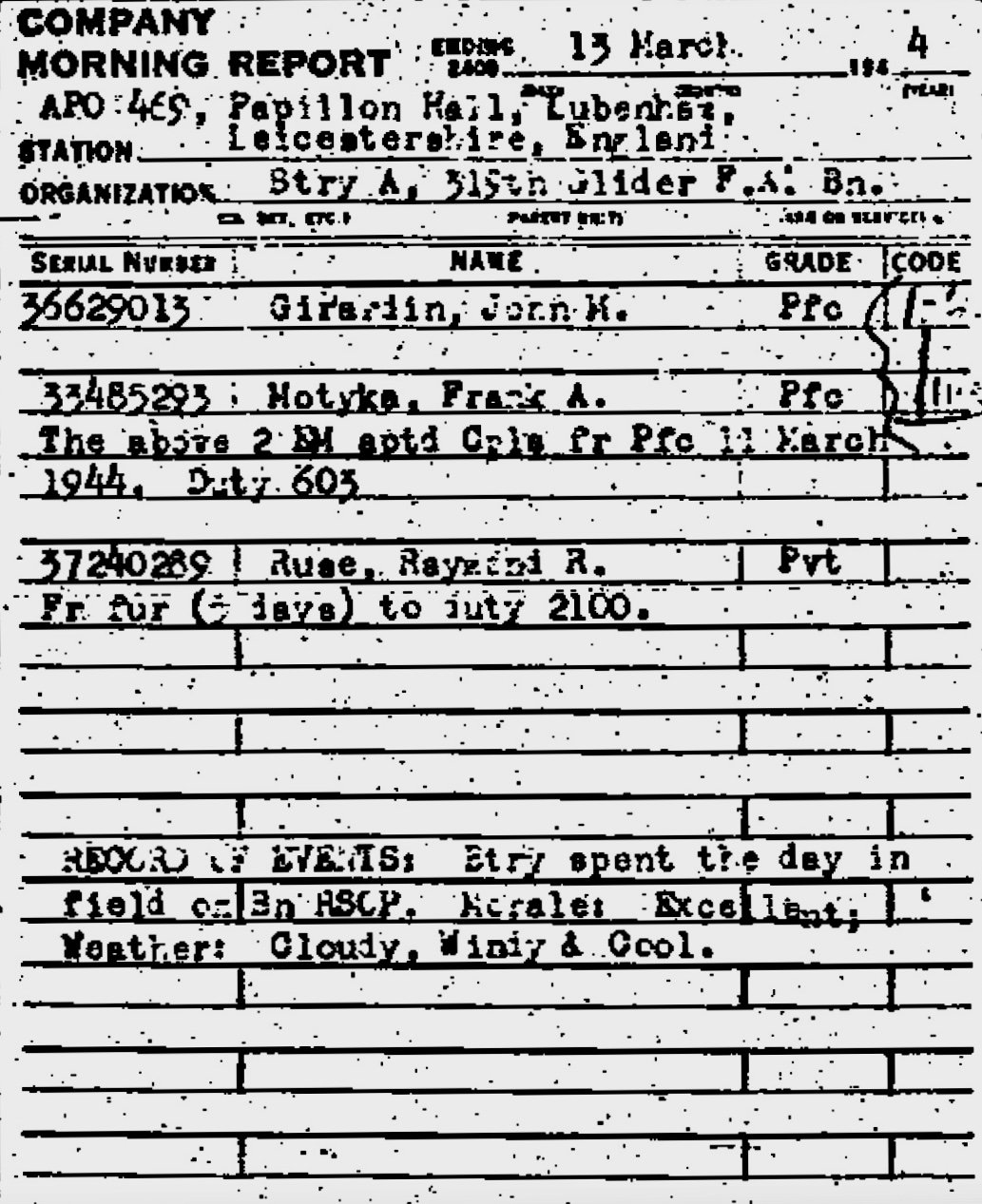

Company Morning Reports

“Company Morning Reports” (CMR) were produced every morning by the individual Army units to record personnel matters. (See below) The following events were reported for John Girardin:

November 7, 1943, from duty to absent sick. Station: Bivouac area 12 miles west of Naples, Italy.

November 13, 1943, from absent sick 95th Evacuation Hospital to duty 1030. Station: Naples, Italy.

November 25, 1943, from duty to sick bay 1100. Station: Docked at Oran, Algeria.

November 28, 1943, from sick bay to duty 1000. Station: Docked at Oran, Algeria.

December 21, 1943, Girardin was promoted from Private to Private First Class.

On January 12, 1944, he was relieved of duty and reported as sick until January 16, 1944 and returned to duty from sick quarters.

Another promotion on March 13, 1994 when he was appointed Corporal from PFC.

July 24, 1944, he received a five-day furlough to Manchester, England returning to duty on July 29, 1944.

On June 11, 1945, Girardin was appointed to Sergeant from Corporal.

May 1945 and the war was over. The US Army used the Adjusted Service Rating Score (ASR) at the end of the war to determine when soldiers were eligible for discharge.

By August 1945, SGT Girardin was now stationed in Berlin, Germany for occupational duty with other 319th soldiers having an ASR score of less than 85. They were housed in what had formerly been a Nazi SS barracks.

Following occupational duties SGT Girardin shipped out to the USA in November 1945, and (See above photos) discharged from the service with Roland Gruebling (R) at Camp McCoy, Tomah, Wisconsin.

Post war years:

Following his honorable discharge John Girardin returned to his home in Rockford, Illinois. He married Olivia Segalla on May 25, 1947, and had a family. He was a machinist and self-employed owner of the Thomas Machine Shop.

In 1966, he attended the 82nd Airborne annual get together (see couples photo below) in Chicago, Illinois, and was a member the 82nd Airborne Association.

He stayed in touch with fellow glidermen, Bart Plassa, Charles Grigus, “Okie” Olkonen, Billy Cadle and Bill Bonnamy. They also celebrated holidays together in Eagle River, Wisconsin, (see photo below) and acted as a godfather to their children.

John M. Girardin, 95, died April 14, 2018. God Bless this hero.

STL Archive Records