Arno Mundt

ASN 36289630

Photo Gallery

(slideshow, side controls to next image)

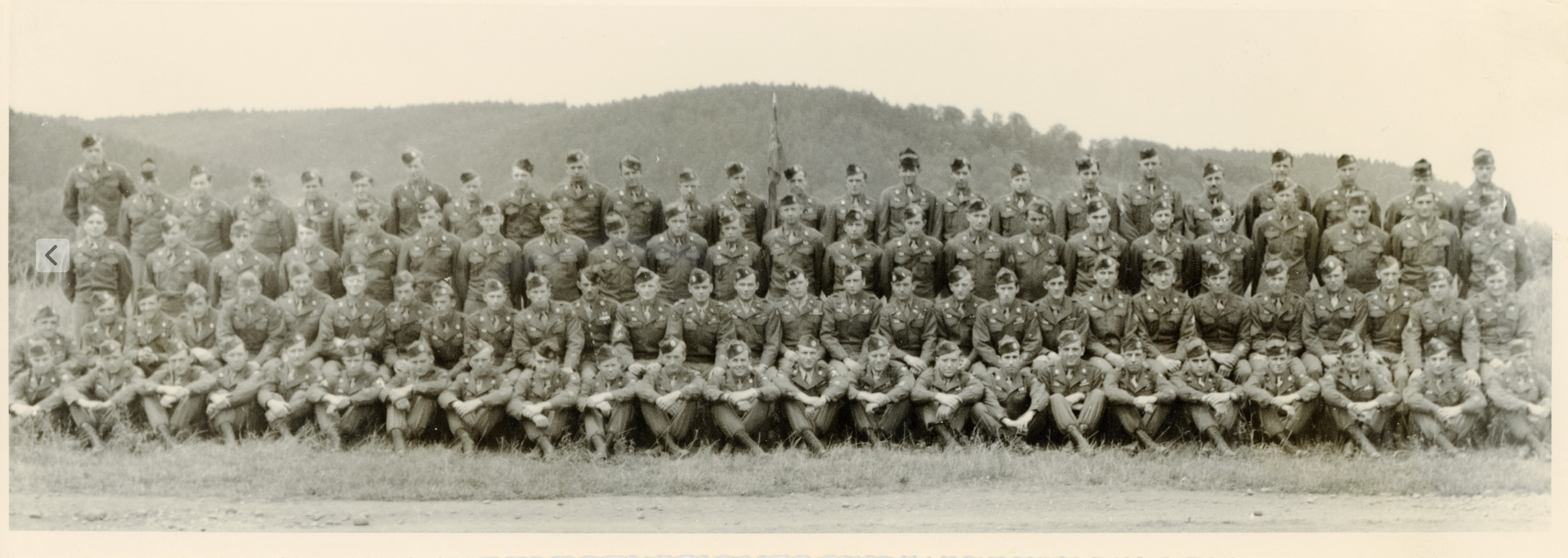

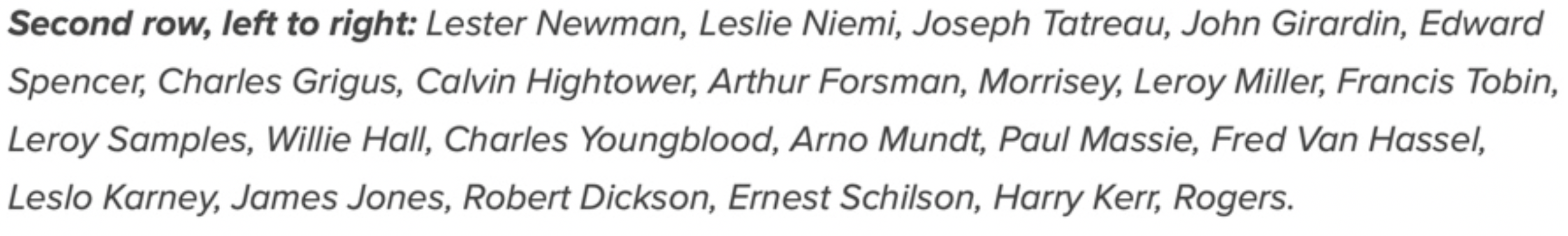

A-Battery 319th Field Artillery Battalion Group Photo - Epinal, France - June 1945

Photos courtesy of the families of Arno Mundt, William Bonnamy

Steve Pongracic and Joseph Covais, author of BATTERY

The personal memoir of Arno Mundt

Courtesy of the Mundt Family and Joseph Covais, author of BATTERY

As the year (1994) approached which would mark the fiftieth anniversary of the D-Day landings I began to long for a way to put to rest my long dormant feelings of incompleteness regarding my part in the war fought so long ago. In December of 1942 I volunteered for service for I knew the draft would soon be enacted and choice of branch of service, etc., would be no longer available. I enlisted in the army for not knowing how to swim I wanted no part of the Navy, I was promised I would not be taken before Christmas, and I signed up with that in mind. The army however had other ideas and in a spirit of "hurry up and wait" my call came on December 22, 1942.

I was mustered in at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. The haircut alone was bad enough to make me not want to be seen, so when the powers that be said I could now return home for my last Christmas, I shuddered at the thought and stayed in the camp, feeling pretty homesick and alone. In fact on my 19th birthday Christmas Eve 1942, I was among the very few guys eating the food in the mess. There was an abundance of food and I gorged myself to combat the loneliness. I never told my family that I passed on that one chance to go home for Christmas.

The uniform I was "fitted" with was of first world war vintage made of heavy wool and the overcoat reached my ankles. The hat was too big and covered my ears making me look like a humorous cartoon by Norman Rockwell. So I was content to stay in the barracks and go to the movies alone. I noticed the other guys were dressed pretty much like me, and I understodd what they were feeling. So Christmas came and went and on the 27th of December we were loaded on a train and were on our way to Fort Bragg in North Carolina. Most of my "buddies" were either hillbillies from Kentucky, West Virginia, Tennessee, and a few from Georgia, and the Carolinas.

The group from the midwest were all from Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois. So I soon got use to hearing southern accents and because most of the hillbillies had no education, I spent time writing their letters home for them. Some of them had never worn shoes and their boots soon became their most valuable possession. And they would polish my boots in exchange for my writing their letters home. Basic training was hard and I can still remember the first day flopping on my bunk so tired I wasn't at all hungry. The next day more of the same and surprisingly by the end of the first week, I was getting used to getting up at 5 a.m. and drilling, and going everywhere "double time."

I was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division which had only recently become "airborne" the first of the whole army to become that. I was assigned to the 319th Field Artillery Battalion Glider Field Artillery and we were soon taking flights. I had never flown before and the whole idea of flying in a glider was so new I just slowly let it all sink in. I heard about the Parachute "jump" school in Fort Benning, Georgia, but at that time Jumping from a plane didn't really appeal to me.

The glider training consisted of loading the very light weight motor-less gliders and flying several times a day. It was exciting and flight became more comfortable. As a kid of 19 I had never been away from home, or driven a car, or flown in a plane much less a glider. But at the time a growing feeling of envy for the glamorous idea of jumping from a plane into combat began to take hold and I was about to ask for a chance at "Jump" school but was told no applications were being accepted.

Then the division was put on alert for transfer overseas. We were given 7 days leave and I now had a uniform that fitted me and thinking surely this would be my last chance to see my family, I took it. The trains were so full of soldiers going home on leave, I had to stand between cars all the way back to Wisconsin. But to tell the truth I would have stood on the platform for a chance to go home. I had the feeling that I would never get back home, and was resigned to be one of the guys who'd die in combat.

The week passed pretty quickly and soon I was back in Fort Bragg and on my way overseas. It was on a refitted "banana" boat and after five long days of sleeping on the deck, we landed in Casablanca, Morocco. It was May 1943, and the hard battles were being fought in Tunisia. We were encamped for one or two nights and my first real bout of homesickness hit me. I was not alone for I could hear some guys actually crying during the night. We were all green kids of average age of 18-19, too young to vote. Then the word came we would be moving closer to action and boarding old French world war 1 railroad "Forty and eights" cars meant to transport 40 men and eight horses to the front lines. We rode for several days in heat with the temps hitting near 100 degrees and came to a city.

Near Algiers, the city of Oujda had nearly 1 million people. The Casbah was off limits to us and seeing all those veiled women gave me no desire to break the rules and see them in another kind of way. Besides, those films on venereal disease burned a hole in my mind and any thoughts of a night on the town with wine, women and song faded quickly when. I remembered the signs of the diseases it was possible to contract. Some of the guys did break the rules and suffered for it. Penicillin had not been commonly used and the treatments were worse than the disease.

We were camped out in the desert where there was no shade. We bathed using our helmets. On a particularly hot day a group of jeeps came to camp and we found ourselves bathing in front of a U.S.O. troupe with the only American girls we'd see for a while. Most of the performers were actually French but the fact they were girls was enough. One of the girls sat on the back of a truck and sang "White Christmas" and there wasn't a dry eye in the crowd. Of course it wasn't Christmas time, but nostalgia hit all of us, first time away from home and realizing that some of us would never live thru the war to see another Christmas at home was too much to bear.

After a few months in Oran, we were moved to Tunisia near a sacred city called Kairouan. We were far from town in an olive orchard surrounded by a hedge almost impenetrable, of prickly pear, a fruit we all learned had tiny needle like spines which became stuck in our tongues, throats, gums and lips. The arabs would simply roll the fruit on the ground with their calloused feet and then nonchalantly eat them like apples. The preliminary step of removing the tiny spines escaped most of us and several days of suffering followed. Once we got use to the fruits we learned to actually enjoy their sweet taste, there were precious few treats available except for life savers, etc, and the daily ration of cigarettes was a single cigarette and so I swapped my cigarette for life savers.

The invasion of Sicily was in July (1943) and we glider troops did not participate. There were grisly tales of our own ships shooting down our own planes abounded and the thought of airborne arrival in combat took on a new light.

The Sicilian campaign ended and the next step was Italy. So in early September 1943 we landed at a beach at night on the Amalfi coast, a beach called Maiori. The night was beautiful and it was hard to believe a war was going on just a few miles away. I remember eating a couple of helmets full of delicious grapes that night. Then we moved up to the mountain to a pass called Chiunzi overlooking the german supply lines which we were to cut. The next day we did so successfully that the German artillery began to bombard us.

I can't remember the shell that got me and three others but the red hot feeling running thru my chest was unmistakable. I was taken by ambulance to a PT boat and to the hospital ship (British) a ship named Aba. The nurses were all "sisters" as the British called them and the one assigned to my ward was a beautiful one. I remember her well for I stumbled to the bathroom down the hall and was in the midst of my moving my bowels when she appeared at the stall door flinging it open and dragging me back to the ward, telling me in no uncertain terms I was to ask for a bedpan from then on. Thoroughly cowered by that I obeyed the rules from then on. In a couple of days we were back in Bizerte and entered a field hospital.

After x-rays, I was told that the shrapnel lodged in my chest had better stay where it was, for the surgery to remove it would be so major that I would have to be sent back to the states for that. At that time I was concerned that I would be made an MP and spend the rest of the war directing traffic far from the front lines. So I took the news pretty well. I relaxed and in my meanderings around the hospital grounds I saw one of the other guys who had fallen on his back and the shrapnel had ripped through his face and taken one eye out. The other two I never saw for their wounds had not been life threatening and they had gone back to the outfit.

I met a devil may care first sergeant in the Royal Fusiliers, a British commando outfit. He had a tattoo on his chest of a battleship and by moving his chest muscles he could make it look like it was sailing. They had to pick shrapnel fragments from his buttocks daily for he had stepped on a mine, a "bouncing betty" which sprayed his body with many shell fragments. He really spent a miserable daily time enduring the hunt for more fragments.

In two weeks I was sent back to the outfit which was now in Naples on a beautiful bay overlooking Mount Vesuvius. The first night we were bombed by the germans and a 500 pound bomb landed just outside the basement bomb shelter we were crowded in. The hole was big enough for a car, as we saw the next day.

The days went by quickly and before Christmas 1943 we were sent to England to prepare for the invasion of Northern France. The trip thru the Mediterranean sea was the roughest in recent history and even the SAILORS got sea sick. My daily meal ticket revealed I didn't eat for three days...the incessant movement of the ship was almost too much too bear. We landed at Algiers and took on supplies, and then sailed out the Gibraltar straits. The North Atlantic was smooth as glass compared to what we had endured.

The threat of torpedoing was very real and we were on black out from dusk to sunrise every day. I spent the evenings keeping the sailors on night watch company and never saw a U-Boat even though at that time they were very active sinking many boats in the area. I spent so much time on the deck one of the sailors asked me if I wanted to transfer to the Navy. Seriously, I wanted to be on deck in case of a torpedoing because my staying three decks below the waterline didn't appeal to me.

The voyage ended at Belfast in Northern Ireland a few weeks before Christmas. The girls who met the boat all were red haired and pale as ghosts. After months in the Mediterranean zone, we were very darkly tanned and they thought we were prisoners of war. It wasn't long before they were clustering around the gates at the end of the day and the guys who got passes were in no lack of dates.

It got dark at 3 in the afternoon and the sun didn't rise until 7 a.m. or so. The songs which were popular at that time were "I'll never smile again," “ I'll walk alone"and the Mills brothers singing "I'm gonna buy a paper doll"...that did nothing to dispel the homesickness we all felt.

Then one day we were sent across the Irish sea to Scotland and in a motor cade went to the Midlands, to a place called Market Harborough, a small town near Leicester, England. Training continued and we were sent to Wales where we were in the Moors. It was like the Moors we'd seen in the movies from the Hounds of the Baskervilles and I almost expected Heathcliff to come out of the mist. The wet cold and lack of sunshine helped prepare us for the months to come in France, Belgium, and Holland.

I was still anxious to try the paratroops for I had begun to really envy their style. Somehow the danger was no deterrent either. So, I applied knowing that the invasion was coming and soon. In March 1944, I entered jump school and the training was really hard. But when the first jump took place, I was amazed at the feeling of excitement. The landing was the hardest part, for it was like jumping about fifteen feet to land on a surface which might be soft, water, or even cement. The first three jumps were over and then the night jump came up. Jumping out of the plane into inky blackness was quite an experience. But the landing was very hard and my ankle twisted and swelled so I couldn't walk on it. The doctor said no more jumps, and I washed out. Going back to the glider outfit was quite a come down and the guys really ribbed me about not making it.

Of course I was very disappointed for I had begun to think like a "trooper" and now that was ended.

The End

STL Archive Records

Arno Mundt, 80, died June 25, 2004. God bless this hero.